![]() https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2024.23409 ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2024.23409 ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

A qualitative exploration of the impact of covid-19 pandemic on research in health professions

Mehreen Lajber ![]() 1,2,

Usman Mahboob

1,2,

Usman Mahboob![]() 2, Imtiaz

Ud Din 1

2, Imtiaz

Ud Din 1

|

1: Medical Teaching Institution Bacha Khan Medical College, Mardan, Pakistan 2: Institute of Health Professions Education and Research, Khyber Medical University, Peshawar, Pakistan

Email

Contact #: +92-333- 9013875

Date Submitted: July 13, 2023 Date Revised: August 25, 2024 Date Accepted: September 20, 2024 |

|

THIS ARTICLE MAY BE CITED AS: Lajber M, Mahboob U, Din IU. A qualitative exploration of the impact of covid-19 pandemic on research in health professions. Khyber Med Univ J 2024;16(3):219-24. https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2024.23409 |

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: To explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on research in health professions.

METHODS: It was a qualitative case study. Semi-structured interviews were done with researchers who were selected through purposive sampling. After thirteen interviews, data saturation was achieved. The interviews were recorded on zoom, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed manually for codes, categories, and themes.

RESULTS: This study explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health research through interviews with researchers, revealing three major themes and thirteen subthemes. The themes encompass the challenges encountered by researchers, the research opportunities provided by the pandemic, and modifications in ongoing and planned projects. All participants expressed that the pandemic brought numerous hurdles, including reduced research opportunities, challenges in data collection, small sample sizes, quality assurance concerns, and delays in project completion. However, it also offered silver linings such as the development of new competencies, a shift in research priorities, and increased reliance on virtual platforms for collaboration and data collection. These findings highlight both the obstacles and innovations prompted by the pandemic in health research.

CONCLUSION: The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted health research, acting as a catalyst for innovation, particularly through the increased use of digital tools and virtual platforms. While researchers faced substantial challenges like disruptions in methodologies and project timelines, these adaptations may persist as integral elements of the research paradigm in health professions, guiding future policy and practice beyond the pandemic.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19 (MeSH); Pandemic (MeSH); Research (MeSH); Health Professions (MeSH); Health Occupations (MeSH).

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed significant challenges for healthcare institutions in providing optimal education and research opportunities to students.¹ It disrupted health professions research, forcing investigators to quickly adopt new technologies, revise protocols, and reconsider long-standing data collection techniques.² Additionally, research resources were largely redirected toward understanding COVID-19, including its pathophysiology, treatment, and prevention.³ Health research, crucial for evidence-based medical practice, gained increased importance as the global community awaited an effective vaccine.⁴ This pandemic underscored the vital role of research in addressing global challenges.⁵ Consequently, research priorities shifted to meet the immediate needs of the pandemic, but this shift has also had unintended consequences on non-COVID-19 research, particularly in health professions.⁶

Understanding how the landscape of health professions research has evolved during the pandemic is essential for better equipping researchers to handle future disruptions. ⁷ While numerous studies have explored the medical, social, and psychological aspects of the pandemic,⁸ the challenges facing non-COVID-related research projects have received less attention.⁹ Researchers have highlighted issues such as resource diversion and funding constraints affecting ongoing health research projects through editorials and viewpoint.¹⁰ However, there is a lack of empirical research exploring the challenges faced by health profession researchers working on non-COVID projects.¹¹ Additionally, it remains unclear whether research quality has improved or declined during the pandemic, emphasizing the need for further investigation into the quality of research in emergency situations.¹²

This qualitative case study was planned to provide insight into the lived experiences of researchers and the long-term impact of the pandemic on health professions research. Through semi-structured interviews, the study explored the challenges, strategies, and innovations in research practices during this unprecedented time. By understanding how research methods have adapted, the study seeks to offer valuable lessons for future research endeavors in health professions, highlighting the importance of resilience and adaptability in the research community. The findings may also inform policies and initiatives designed to support the research sector during crises, helping the medical community maintain its research projects despite disruptions. Ultimately, this study will help in assessing the broader impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health professions research and its potential future implications.

METHODS

A qualitative case study design was chosen for this research as it allowed for an in-depth exploration of the selected unit of analysis in its real-life contextual settings. ¹³ This approach is effective for investigating a phenomenon within a bounded system, and in this study, health profession specialties were considered the bounded system. Researchers actively engaged in pre-pandemic research were selected, allowing for a comparison of the challenges faced during different research phases, both before and during the pandemic. Purposive sampling was employed, and the maximum variation technique was applied to include researchers from diverse specialties, ensuring a broad spectrum of perspectives. Participants were drawn from various departments, including Health Professions Education, Public Health, Basic Medical Sciences, Clinical Sciences, and Physiotherapy across different institutions in Pakistan. These institutions included Khyber Medical University Peshawar, Riphah International University Islamabad, Health Services Academy Islamabad, Bacha Khan Medical College Mardan, Jinnah Sindh Medical University Karachi, KMU Institute of Medical Sciences Kohat, and Sharif Medical and Dental College Lahore. This method provided depth and consistency in the data, enabling comparative analysis while ensuring that the data collected was relevant to the research question. By focusing on pre-existing research projects, we could gain clearer insights into how the pandemic disrupted ongoing research efforts, rather than observing the initiation of new projects during the pandemic, which streamlined the data collection process.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and semi-structured interviews were conducted via Zoom from the 1st of August 2021 to the 30th of November 2021. The interview guide was developed through five phases, ¹⁴ beginning with a preliminary guide based on the study’s objectives and a review of the existing literature. Pilot interviews were conducted with expert researchers to assess the flow of questions, average interview duration, logistical requirements, and to refine the data analysis protocol. The finalized semi-structured interview guide consisted of eight questions, comprising one engagement question, six exploratory questions, and one exit question. Interviews, lasting an average of 30 minutes, were transcribed using Otter.ai software.

Thematic analysis was performed manually, following Braun and Clarke’s six-step framework. ¹⁵ The research team members (ML, UM, and IU) initially coded the transcripts independently before discussing and finalizing the codes and identifying themes through online meetings. Theoretical saturation was achieved by the thirteenth interview, as no new information emerged. To reduce potential researcher bias, the findings were shared with participants for validation.

The research team comprised members with experience in medical education, public health, and basic sciences research, all of whom had firsthand experience navigating the evolving research landscape during the pandemic. This personal involvement allowed the team to reflect on the participants' data and relate it to their own experiences, particularly concerning the challenges of data collection during the pandemic.

Quality assurance measures for qualitative research, such as credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability, were followed. Additionally, the study adhered to the COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research) guidelines, a 32-item checklist designed to ensure the quality of qualitative studies. ¹⁶

RESULTS

Interviews provided valuable insights into three key areas:

1. Difficulties faced by researchers.

2. New research opportunities provided by the pandemic.

3. Modifications in ongoing and planned projects.

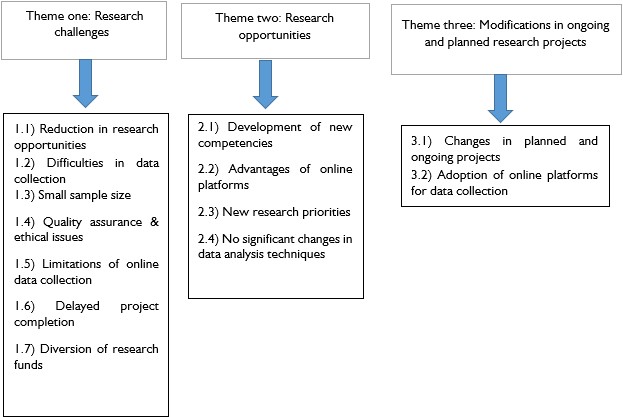

Data is organized into themes and subthemes (see Figure 1), and relevant interview quotations are detailed in Tables I, II, and III, categorized by participant number and specialty.

Figure 1: Three themes and thirteen sub-themes

Table I: Representative quote for each subtheme regarding research challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic

|

Theme |

Sub-Theme |

Representative quote |

|

Research Challenges |

Reduction in research opportunities

|

“Some running community-based projects were stopped because we do not want to expose our students or researchers to the community and suffer from COVID-19. So, we have to stop our projects for three or four months”. (P4 Basic Sci) |

Difficulties in data collection |

“…we were struggling with the data collection. Because when we were recruiting healthy participants, they denied it. So firstly, in the recruitment phase, we were struggling. Secondly, when we went to the hospitals, the hospital was not admitting the patients”. (P8 Basic Sci) |

|

Small sample size

|

“…we were unable to collect 20 or 30 participants. For example, we had to reduce participants during one of my projects with participatory action research. Instead of doing a focus group discussion with 15 or 16 participants, we reduced the number to six or seven participants.”. (P4 Basic Sci) |

|

|

|

“There was low-quality research coming up. As everybody was free and had the opportunity to conduct research but had not given enough time to research proposal development, research was conducted in a hurry, so poor-quality research was done”. (P13 Physiotherapy) “Ethical approval was also a significant issue as we could not get ethical approval urgently. Although the National Ethics Committee tried to give ethical approval within three to four days, even that was not appropriately reviewed. So, there was a compromised ethical review”. (P1 Clinical Sci) |

|

Limitations of online data collection

|

“…not all types of data can be collected well online. For example, we had reflections from different countries like Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh from a multi-country project that I am leading. We conducted telephonic interviews when we were supposed to do it face-to-face. Moreover, the telephonic interviews had their challenges; the data collection was not as robust as it could have been with face-to-face contact”. (P6 Public Health) |

|

|

Delayed project completion |

“The projects planned before the pandemic had setbacks in terms of resources and time, and they had to increase their time duration”. (P3 Med Educ) |

|

Diversion of research funds |

“Research funds were transferred to COVID-19 related research and effectiveness of online platforms for teaching and learning”. (P2 Med Educ) |

Table II: Representative quote for each subtheme in research opportunities during the Covid-19 Pandemic

|

Theme |

Sub-theme |

Representative quote |

Research Opportunities |

Development of new competencies

|

“…I collected the data on a zoom interview. I wanted to transcribe it. So, I just got into the software Otter.ai. It timestamps the whole interview and transcribes the data based on voice recognition. So, I think that probably would not have come to my mind if I was not more focused on using the software during this COVID-19 pandemic”. (P7 Med Educ) |

New research priorities

|

“… everybody, irrespective of their research interest, for the greater good of humanity, and perhaps public health, many people did COVID-19 related research, and so we did”. (P6 Public Health) |

|

Advantages of online platforms

|

“Many new linkages have been developed with international colleagues and national colleagues. Similarly, previously, if we had to do a seminar, we had to invite people nationally or internationally; they had to come and join physically. So, many resources were required for those interactions, but with COVID, it all changed. So, there were many opportunities that people would join online. Moreover, they would be international experts in their fields, and people can learn from them wherever they are. So, I think that was the positive aspect of all this”. (P11 Public Health) |

|

|

No change in data analysis techniques

|

“I think the data analysis was already based on computer software, either SPSS or Qualitative Software such as Atlas. ti or NVivo, and even some people were doing manual analysis. So, during data analysis, I do not think there were any specific or many changes”. (P3 Med Educ) |

Table III: Representative quote for each subtheme in nodification in ongoing and planned research projects during the COVID-19 pandemic

|

Theme |

Sub-theme |

Representative quote |

|

Modification in ongoing and planned projects |

Changes in ongoing and planned projects |

“One of our colleagues from ophthalmology was doing her research on peer-assisted learning in ophthalmology ward rotation. However, when the pandemic started, the students were not allowed to go to the hospital. So, she had to switch to online teaching classes. Therefore, she used the online peer-assisted learning sessions she planned for it. She could not do it in the ward rotation; thus, she used it in her online ophthalmology module. So, she used peer-assisted learning as a teaching strategy. Then she did qualitative research of the students’ experiences of peer-assisted learning on knowing about its effectiveness”. (P3 Med Educ) |

Adoption of online platforms for data collection |

“Many surveys and interviews were conducted online. I did many research projects in which we designed google forms and interviewed the health workers”. (P11 Public Health) |

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed that, while the COVID-19 pandemic posed numerous challenges for researchers, it also opened new opportunities. The findings of our study provide valuable insights into the experiences of researchers during this period. Initially, the pandemic led to a global disruption of economies, travel, and research activities on an unprecedented scale, consistent with findings by Omary MB, et al.¹⁷ Similarly, research by Cardel MI, et al., highlighted the significant difficulties researchers faced in recruiting participants due to COVID-19 restrictions, which reduced participants' willingness to engage in research.¹⁸ Furthermore, attaining an adequate sample size proved to be a major challenge, prolonging the duration of research projects. This aligns with literature suggesting that the number of patients reporting to hospitals, aside from those with COVID-19, was significantly reduced, complicating efforts to meet sample size requirements.¹⁹

One of the main advantages observed during the pandemic was the increased use of remote and virtual research methods. Online platforms enabled the continuation of research activities, as researchers adapted to these platforms for data collection and collaboration. This shift expanded the scope of studies and allowed access to more diverse participant groups. However, researchers initially encountered challenges transitioning to online methods. Data collection through virtual platforms often lacked the depth of face-to-face interactions. Additionally, issues such as poor connectivity and voice quality created obstacles during online data collection. These findings align with existing literature, which acknowledges both the benefits and limitations of online data collection. ²⁰ Similarly, literature also highlights that quality assurance and ethical concerns were not adequately addressed during the pandemic.²¹ Many researchers, eager to continue publishing during lockdown, contributed to a surge in open-access publications. Some journals, in response, adopted more flexible peer-review processes, leading to the publication of lower-quality articles, even in high-impact factor journals.²² Moreover, as research priorities shifted toward COVID-19, funding for non-COVID-related projects was significantly reduced, a challenge corroborated by a previous study.²³

Moreover, all participants agreed that COVID-19 remained the predominant focus of research during the pandemic, which aligns with the findings of Ruiz-Real JL.⁸ Researchers also became more adept at using online tools. Online conferences, for example, saved resources and offered opportunities for the global exchange of ideas and continued professional development. ²⁴ The literature highlights that institutions and individuals who adapt to such evolving situations are poised to become future leaders, driving innovative research and collaboration. ²⁵

Another critical point highlighted in our study was that researchers had not anticipated the pandemic when designing their projects. As a result, several projects had to be either redesigned or modified, including the adoption of online platforms for conducting surveys as well as both qualitative and quantitative studies. These outcomes align with the findings of O'Brien BC¹⁰ and Torrentira MC.²⁶ The COVID-19 pandemic compelled individuals and institutions to think creatively and strategically, fostering new and enhanced methods of conducting research and maintaining connectivity in an increasingly digital world.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of the current study. The research was confined to a specific geographical area, Pakistan, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the use of semi-structured online interviews could have introduced bias, as variations in participants' familiarity with technology and potential connectivity issues may have affected the depth and quality of the data collected. Moreover, this study primarily focused on researchers' experiences during the pandemic, without exploring the long-term impact or the evolution of research practices in the post-pandemic period. Therefore, future longitudinal studies are needed to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the long-term effects of pandemics on health professions research.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic has driven the identification of more efficient research methods in the health professions, offering researchers valuable opportunities for learning, adaptation, and innovation. It highlighted the critical need for contingency planning to protect research from unforeseen disruptions. During this period, the health professions research community exhibited remarkable resilience and adaptability. The innovative techniques developed in response to the pandemic hold the potential to enhance and transform future research practices. However, it is essential to address the quality and ethical implications of these evolving methods. While the increased use of online platforms has improved researchers' technical proficiency, maintaining scientific rigor is crucial to ensure the effectiveness of these digital approaches in generating robust evidence. Researchers must continue to experiment with and assess these new methods, critically reflecting on their outcomes. Additionally, policymakers must ensure that research priorities are aligned with the evolving landscape of health professions research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We extend our sincere gratitude to all the participants who generously contributed their time and insights to this study.

REFERENCES

1. Corson TW, Hawkins SM, Sanders E, Byram J, Cruz LA, Olson J, et al. Building a virtual summer research experience in cancer for high school and early undergraduate students: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Med Educ 2021;21(1):1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02861-y.

2. Moises C, Torrentia Jr. Online data collection as adaptation in conducting quantitative and qualitative research during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Edu Stud 2020;7(11):78-87. https://doi.org/10.46827/ejes.v7i11.3336.

3. Chahrour M, Assi S, Bejjani M, Nasrallah AA, Salhab H, Fares MY, et al. A Bibliometric analysis of COVID-19 research activity: a call for increased output. Cureus 2020;12(3):1-8. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7357.

4. Kent P, Keating J, Bernhardt J, Carroll S, Hill K, McBurney H. Evidence-based practice. Aust J Physiother 1999;45(3):167-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0004-9514(14)60347-0.

5. Yazdizadeh B, Majdzadeh R, Ahmadi A, Mesgarpour B. Health research system resilience: lesson learned from the COVID-19 crisis. Heal Res Policy Syst 2020;18(1):1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00667-w.

6. Elsevier BV. Research and higher education in the time of COVID-19. Lancet 2020;396(10251):583. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31818-3.

7. Fernandes L, FitzPatrick ME, Roycrof M. The role of the future physician: building on shifting sands. Clin Med 2020;20(3):285-9. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2020-0030.

8. Ruiz-Real JL, Nievas-Soriano BJ, Uribe-Toril J. Has COVID-19 gone viral? an overview of research by subject area. Health Educ Behav 2020;47(6):861-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198120958368.

9. Yanow SK, Good MF. Nonessential research in the new normal: the impact of COVID-19. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2020;102(6):1164-5. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0325.

10. O’Brien BC, Teherani A, Boscardin CK, O’Sullivan PS. Pause, persist, pivot: key decisions health professions education researchers must make about conducting studies during extreme events. Acad Med 2020;95(11):1634-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003535.

11. Bratan T, Aichinger H, Brkic N, Rueter J, Apfelbacher C, Boyer L, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on ongoing health research: an ad hoc survey among investigators in Germany. BMJ Open 2021;11(12):1-7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049086.

12. Pezzullo AM, Ioannidis JPA, Boccia S. Quality, integrity and utility of COVID-19 science: opportunities for public health researchers. Eur J Public Health 2023;33(2):157-8. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckac183.

13. Priya A. Case study methodology of qualitative research: key attributes and navigating the conundrums in its application. Sociological Bull 2021;70(1):94-110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038022920970318.

14. Naz N, Gulab F, Aslam M. Development of qualitative semi-structured interview guide for case study research. Competitive Soc Sci Res J 2022;3(2):42-52. https://cssrjournal.com/index.php/cssrjournal/article/view/170.

15. Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Terry G. Thematic analysis. In: Liamputtong P ed, Handbook of research methods in health social sciences Springer, Singapore. 2018;843-60. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2779-6_103-1.

16. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Heal Care 2007;19(6):349-57. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

17. Omary MB, Eswaraka J, Kimball SD, Moghe PV, Panettieri RA, Scotto KW. The COVID-19 pandemic and research shutdown: staying safe and productive. J Clin Invest 2020;130(6):2745-8. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI138646.

18. Cardel MI, Manasse S, Krukowski RA, Ross K, Shakour R, Miller DR, et al. COVID-19 impacts mental health outcomes and ability/desire to participate in research among current research participants. Obesity 2020;28(12):2272-81. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23016.

19.; Kalanj K, Marshall R, Karol K, Tiljak MK, Orešković S. The Impact of COVID-19 on hospital admissions in Croatia. Front Public Health 2021;9:720948. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.720948.

20. Hensen B, Mackworth-Young CRS, Simwinga M, Abdelmagid N, Banda J, Mavodza C, et al. Remote data collection for public health research in a COVID-19 era: ethical implications, challenges and opportunities. Health Policy Plan 2021;36(3):360-8. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czaa158.

21. Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ. Fundamental shifts in research, ethics and peer review in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Korean Med Sci 2020;35(45):e395. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e395.

22. Zdravkovic M, Berger-Estilita J, Zdravkovic B, Berger D. Scientific quality of COVID-19 and SARS CoV-2 publications in the highest impact medical journals during the early phase of the pandemic: a case-control study. PLoS One 2020;15(11):e0241826. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241826.

23. Sethi BA, Sethi A, Ali S, Aamir HS. Impact of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on health professionals. Pak J Med Sci 2020;36(COVID19-S4):S6-11. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2779.

24. Purvis M. Learning to love-virtual conferences. Nature 2020;582:135-6. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01489-0.

25. Mahboob U, Sherin A. Future of online medical education. Khyber Med Univ J 2020;12(3):175-6. https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2020.20753.

26. Moises C, Torrentia Jr. Online data collection as adaptation in conducting quantitative and qualitative research during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Eur J Educ Stud 2020;7(11):78-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.46827/ejes.v7i11.3336

Following authors have made substantial contributions to the manuscript as under:

ML: Study design, acquisition, analysis of data, drafting the manuscript, approval of the final version to be published UM: Concept and study design, analysis of data, critical review, approval of the final version to be published IUD: Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, critical review, approval of the final version to be published

Authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. |

|

CONFLICT OF INTEREST Authors declared no conflict of interest, whether financial or otherwise, that could influence the integrity, objectivity, or validity of their research work.

GRANT SUPPORT AND FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE Authors declared no specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors |

|

DATA SHARING STATEMENT The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request |

|

|

|

KMUJ web address: www.kmuj.kmu.edu.pk Email address: kmuj@kmu.edu.pk |