![]() https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2023.23338

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2023.23338

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Knowledge and barriers associated with contact lens use among spectacle wearers

Umm-e-Aiman 1,

Muhammad Sadiq1![]() , Fareeha Ayub 1,

Khizar Nabeel Ali2

, Fareeha Ayub 1,

Khizar Nabeel Ali2

|

1: Pakistan Institute of Ophthalmology, Al-Shifa Trust Eye Hospital, Rawalpindi, Pakistan 2: Al-Shifa School of Public Health, Al-Shifa Trust, Rawalpindi, Pakistan

Email

Contact #: +92-334-7213705 Date Submitted: March01, 2023 Date Revised: November 21, 2023 Date Accepted: November27, 2023 |

|

THIS ARTICLE MAY BE CITED AS: Umm-e-Aiman, Sadiq M, Ayub F, Ali KN. Knowledge and barriers associated with contact lens use among spectacle wearers. Khyber Med Univ J 2023;15(4):247-53. https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2023.23338 |

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: To determine the knowledge and barriers to contact lens usage among spectacle wearers.

METHODS: This cross-sectional study was conducted from November 2020 to January 2021 on the spectacle wearers visiting Al-Shifa Trust Eye Hospital, Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Data were obtained from all the respondents of either gender, aged between 18 and 50 years, using a structured questionnaire after obtaining informed consent.

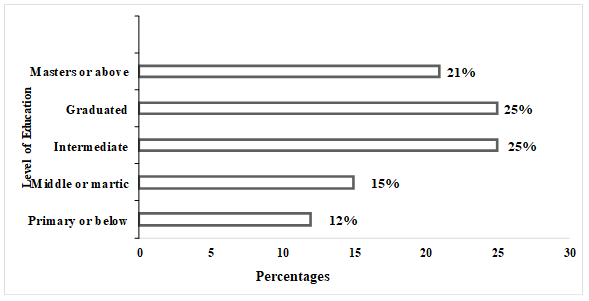

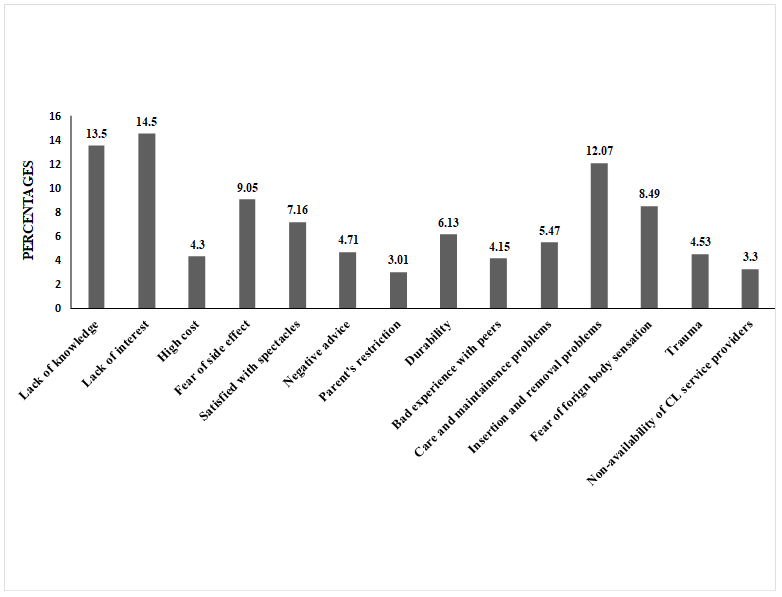

RESULTS: Out of 362 study respondents, 184 (50.8%) were females, 248 (68.5%) hailed from urban areas, 92 (25%) were graduates. Mean age of participants was 35.94 ± 10.56 years. Majority (n=170; 47.0%) had Myopia, followed by Astigmatism (n=56; 15.5%). A majority (n=284;78.5%) expressed satisfaction with their spectacles. Overall, 246 (68%) individuals were aware of contact lenses, and 184 (50.8%) participants were knowledgeable about the dual usage of contact lenses for both cosmetic and correction purposes. Females (63.6%) had more knowledge about contact lenses than males (53.9%). Barriers to contact lens wear reported were lack of interest (14.5%), lack of knowledge (13.5%), difficulty in insertion and removal (12.7%), and fear of side effects (9.5%). The younger adults and those from urban areas were more likely to know about contact lenses. A significant association was seen among barriers and demographics of respondents (p-value 0.012).

CONCLUSION: Despite having good knowledge of contact lenses, people were not interested in using them as an alternative vision correction tool. Educating people about contact lenses and conducting experimental trials for visual performance on potential candidates may help overcome the barriers to wearing contact lenses.

KEYWORDS: Knowledge (MeSH); Barriers (Non-MeSH); Contact Lenses (MeSH); Refractive Errors (MeSH);Eyeglasses (MeSH);Myopia (MeSH); Astigmatism (MeSH).

INTRODUCTION

Refractive errors, compromising the eye's ability to focus light accurately on the retinal plane, result in visual impairments such as myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism.1,2Spectacles (glasses) stand out as the predominant and most effective means of correcting refractive errors, thereby improving visual performance. In addition to spectacles, contact lenses are utilized for the correction of ametropia. Individuals who opt for contact lenses often report an enhanced quality of life compared to those who wear spectacles.3 These lenses, whether corrective, cosmetic, or therapeutic, are placed directly on the cornea.4 While they offer superior cosmetic appeal, the challenge lies in the demanding care and maintenance required for contact lenses, leading to potential complications and alterations in the corneal surface.3

In 2012, global estimates revealed that over 2.3 billion individuals were grappling with vision problems.1 Subsequently, a population-based survey conducted in the United States identified approximately 4.9 million people who opted for contact lenses.5 The United Kingdom witnessed a notable surge in contact lens wearers, escalating from 1.6 million in 1992 to 3.5 million in 2014, and further to 3.7 million in 2016.6 Comparable trends were observed in Saudi Arabia, the USA, and Japan, where the prevalence of contact lens wearers ranged from 17% to 70%.7,8

In contrast to the widespread popularity of contact lenses, a critical issue emerged – 80% of complications associated with contact lens usage were attributed to poor patient compliance with recommended lens care guidelines.9 This concern manifested in various aspects of contact lens wear and care, with inadequate hygiene practices and microbial contamination of lens cases identified as culprits, leading to conditions such as microbial keratitis.10,11 This problem is exacerbated in tropical climates, where environmental conditions favor the proliferation of microorganisms.9 Consequently, there is an urgent need to emphasize the evaluation, care, and follow-up of contact lens wearers in such regions.

Despite the well-established awareness among spectacle wearers, studies consistently demonstrated a reluctance to adopt alternatives to spectacles. Overcoming this resistance necessitates targeted efforts, including education initiatives, dispelling fears related to complications, and improving the affordability of alternatives such as contact lenses. 12,13 Myths and misconceptions surrounding contact lenses further impede their widespread adoption.3

Remarkably, in acknowledgment of these complications, a significant 87% of individuals expressed a preference for contact lenses for cosmetic purposes.14 Despite the perceived challenges in terms of cost and application intricacies, contact lenses offer a myriad of advantages that surpass those provided by spectacles.1 People persist in using spectacles, enduring issues such as nose weight, ear pressure, limited field of view, and lens fogging in adverse weather conditions. The potential for contact lenses to provide a more natural vision, unhindered by blockages and resistant to weather-induced impediments, makes them an attractive alternative.

This imperative becomes especially pronounced in regions such as Pakistan, where the interplay of climatic conditions and cultural factors may introduce distinctive challenges that remain inadequately investigated in current research.15 The limited exploration of these specific challenges in existing studies underscores the urgent need for more comprehensive investigations. By focusing on regions like Pakistan, this study aims to highlight the critical gaps in our understanding and emphasizes the necessity for additional research to resolve the complexities associated with contact lens adoption in diverse cultural and environmental contexts.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted from November 2020 to January 2021, at Al-Shifa Trust Eye Hospital, Rawalpindi, Pakistan. A structured questionnaire was used to find out the knowledge and barriers associated with contact lens usage among individuals who primarily use spectacles.

Prior to the initiation of this study, ethical approval was granted by the hospital's ethical committees. The study strictly adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964. Additionally, explicit consent was obtained from all patients, permitting the utilization of their data for research purposes.

Data was gathered from individuals who wore spectacles, encompassing both genders and falling within the age range of 18 to 50 years, during their visits to Al-Shifa Trust Eye Hospital. Participants with any other ocular pathology or concurrent physical or mental illnesses were excluded from the study. Although the initially calculated sample size was 350, information was collected from 362 participants to account for potential non-respondents. The determination of the sample size utilized the online software OPENEPI, considering the previous prevalence recorded in Ghana in 2017, which was 34.8%.4

The data collected underwent analysis utilizing the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17. Descriptive analysis involved the generation of frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, which were then presented through tables, graphs, and charts. To determine the association between outcome variables and independent variables, the Chi-square test was employed, and a significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically.

RESULTS

Interviews were conducted with a total of 362 participants, exhibiting a mean age of 35.94 ± 10.56 years. The gender distribution was nearly balanced, and the majority, constituting 265 individuals (73.2%), were married. Additionally, a significant portion (n=248; 68.5%) hailed from urban areas. (Table I).

Table I: Demographic details of the study participants

|

Variables |

Categories |

Frequencies (N) |

Percentages (%) |

|

Age (in years) |

18-20 |

41 |

11.3 |

|

21-30 |

86 |

23.8 |

|

|

31-40 |

98 |

27.1 |

|

|

41-50 |

137 |

37.8 |

|

|

Gender |

Male |

178 |

49.2 |

|

Female |

184 |

50.8 |

|

|

Marital status |

Married |

265 |

73.2 |

|

Un-married |

97 |

26.8 |

|

|

Occupation |

Student |

60 |

16.6 |

|

Housewife |

70 |

19.3 |

|

|

Teacher or banker |

87 |

24.0 |

|

|

Shopkeeper or driver |

18 |

5.0 |

|

|

Govt; employee |

46 |

12.7 |

|

|

Private/ other |

81 |

22.4 |

|

|

Socioeconomic history |

Normal |

121 |

33.4 |

|

Good |

204 |

56.4 |

|

|

Excellent |

36 |

10.0 |

|

|

Residency |

Rural |

114 |

31.5 |

|

Urban |

248 |

68.5 |

The majority of participants, 246 (68%) knew about contact lenses, while 239 (66%) and 210 (58%) didn’t know about the handling of contact lenses with makeup or replacing contact lens case respectively. One hundred and ninety-six (54%) and 141 (39%) participants respectively believed that sleeping and swimming while wearing contact lenses can affect the eyes. About half of the participants didn’t know about the effect of contact lenses to decrease visual acuity (52%) or complications that may lead to blindness (47%) while 318 (87.8%) also didn’t know about the solutions for contact lenses (Table Table II)

Table II.: Summary of the knowledge associated with contact lenses of respondents

|

Variable |

Category |

Frequency (N) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Knowledge of contact lenses |

No |

116 |

32 |

|

Yes |

246 |

68 |

|

|

Purpose of wearing contact lenses |

Don’t know |

108 |

29.8 |

|

Cosmetic |

23 |

6.4 |

|

|

Correction |

47 |

13.0 |

|

|

Both |

184 |

50.8 |

|

|

Wearing of contact lenses with makeup |

Don’t know |

239 |

66.0 |

|

After makeup |

80 |

22.1 |

|

|

Before makeup |

43 |

11.9 |

|

|

Replace contact lenscases |

Don’t know |

210 |

58.0 |

|

Daily |

9 |

2.5 |

|

|

Weekly |

60 |

16.6 |

|

|

Monthly |

83 |

22.9 |

|

|

Place to purchase contact lenses |

Don’t know |

125 |

34.5 |

|

Beauty salons |

16 |

4.4 |

|

|

Optical shops |

87 |

24.0 |

|

|

Eye care practitioners |

134 |

37.0 |

|

|

Place to keep contact lenses |

Don’t know |

149 |

41.2 |

|

Glass box |

26 |

7.2 |

|

|

Disinfectant |

97 |

26.8 |

|

|

In its case and solution |

90 |

24.9 |

|

|

Swimming effect |

Yes |

141 |

39 |

|

No |

18 |

5 |

|

|

Don’t Know |

203 |

56 |

|

|

Sleeping effect |

Yes |

196 |

54 |

|

No |

11 |

3 |

|

|

Don’t Know |

155 |

43 |

|

|

Decrease in visual acuity |

Don’t know |

188 |

51.9 |

|

Yes |

83 |

22.9 |

|

|

No |

91 |

25.1 |

|

|

Complications by contact lenses |

Don’t know |

170 |

47 |

|

Yes |

124 |

34.3 |

|

|

No |

68 |

18.8 |

|

|

Solution used for contact lenses |

Yes |

44 |

12.2 |

|

No |

318 |

87.8 |

|

|

Lens usage in future |

Yes |

37 |

10.3 |

|

No |

193 |

53.3 |

An association between knowledge and demographic variables was analyzed and overall good knowledge was seen among 213 (58.8%) participants. A significant association between knowledge about contact lenses and age, marital status, and occupation was noted in participants in the age group 21-30 years (p <0.001), unmarried participants (p 0.001), and students (p <0.001). The participants having maximum good knowledge were satisfied with their spectacles (p 0.010), from urban areas, and had masters or above (Table III).

Table III: Association between knowledge and sociodemographic of the respondents

|

Variables |

Categories |

Good knowledge |

Poor knowledge |

Chi-square (df) |

p-value |

|

Age |

18-20 |

29 (70.7%) |

12 (29.3%) |

26.69 (3) |

<0.001* |

|

21-30 |

66 (76.7%) |

20 (23.3%) |

|||

|

31-40 |

59 (60.2%) |

39 (39.8%) |

|||

|

41-50 |

60 (43.8%) |

77 (56.2%) |

|||

|

Gender |

Male |

96 (53.9%) |

82 (46.1%) |

3.482 (1) |

0.062 |

|

Female |

117 (63.6%) |

67 (36.4%) |

|||

|

Marital status |

Married |

142 (53.6%) |

123 (46.4%) |

11.276 (1) |

0.001* |

|

Un-married |

71 (73.2%) |

26 (26.8%) |

|||

|

Occupation |

Students |

54 (90%) |

6 (10%) |

57.33 (5) |

<0.001* |

|

Housewife |

27 (38.6%) |

43 (61.4%) |

|||

|

Teacher or banker |

57 (65.5%) |

30 (34.5%) |

|||

|

Shopkeeper/driver |

2 (11.1%) |

16 (88.9%) |

|||

|

Government employ |

22 (47.8%) |

24 (52.2%) |

|||

|

Private/other |

51 (63%) |

30 (37%) |

|||

|

Residency |

Rural |

39 (32.5%) |

75 (67.5%) |

42.706(1) |

<0.001* |

|

Urban |

175 (71%) |

73 (29%) |

|||

|

Education |

Masters or above |

63 (83.5%) |

17 (16.5%) |

95.18(4) |

<0.001* |

|

Graduate |

80 (82.6%) |

12 (17.4%) |

|||

|

Intermediate |

47 (53.8%) |

44 (46.2%) |

|||

|

Matric/Middle |

23 (33.9%) |

33 (66.1%) |

|||

|

Primary/Illiterate |

5 (6.8%) |

39 (93.2%) |

|||

|

Socio-economic history |

Normal |

31 (25.6%) |

90 (74.4%) |

85.942 (2) |

<0.001* |

|

Good |

150 (73.3%) |

55 (26.8%) |

|||

|

Excellent |

32 (88.9%) |

4 (11.1%) |

|||

|

Refractive status |

Myopia |

105 (61.8%) |

65 (38.2%) |

25.220 (3) |

<0.001* |

|

Astigmatism |

43 (76.8%) |

13 (23.2%) |

|||

|

Presbyopia |

7 (22.6%) |

24 (77.4%) |

|||

|

Mixed |

59 (56.2%) |

46 (43.8%) |

|||

|

State of glasses |

Single vision |

189 (59.2%) |

130 (40.8%) |

0.184 (1) |

0.668 |

|

Bifocals |

24 (55.8%) |

19 (44.2%) |

|||

|

Astigmatic correction |

Yes |

98 (60.5%) |

64 (39.5%) |

0.230 (1) |

0.631 |

|

No |

116 (58.0%) |

84 (42.0%) |

|||

|

Number of changes in spectacle number |

Never |

45 (57%) |

34 (43%) |

3.657 (4) |

0.454 |

|

1-2 times |

60 (53.1%) |

53 (46.9%) |

|||

|

>3-5 times |

31 (63.3%) |

18 (36.7%) |

|||

|

>10 times |

23 (65.7%) |

12 (34.3%) |

|||

|

Several times |

55 (64%) |

31 (36%) |

The association between barriers and demographic variables of respondents is explained in Table VI, and a significant association was seen among age and residency with lack of knowledge (p <0.001), gender with fear of side effects (p 0.002), socioeconomic status and occupation with satisfaction with glasses (p 0.001). Education of respondents showed a significant association with lack of knowledge (p <0.001), not interested (p 0.008), fear of side effects (p 0.001), and Satisfied with spectacles (p <0.001).

Table VI: Association between barriers and demographics of respondents

|

Demographic Variables |

Categories/Barriers |

Lack of Knowledge |

Not Interested |

High Cost |

Fear of side effects |

Satisfied with spectacles |

|||||

|

Response |

Positive |

Negative |

Positive |

Negative |

Positive |

Negative |

Positive |

Negative |

Positive |

Negative |

|

|

Age |

18-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 |

7(17.07%) 13(15.1%) 38(38.7%) 80(58.3%) |

34(82.9%) 73(84.8%) 60(61.2%) 57(41.6%) |

12(29.2%) 28(32.5%) 44(41.8%) 70(51.1%) |

29(70.7%) 58(67.4%) 54(59.1%) 67(48.9%) |

2(4.87%) 14(16.2%) 12(12.2%) 18(13.1%) |

39(95.1%) 72(83.7%) 86(87.7%) 119(86.9%) |

13(31.7%) 27(31.3%) 29(29.5%) 27(18.2%) |

28(68.2%) 59(68.6%) 69(70.4%) 110(80.2%) |

7(17.07%) 25(29.1%) 19(19.3%) 25(18.2%) |

34(82.9%) 61(70.9%) 79(80.6%) 112(81.7%) |

|

P-Value |

<0.001 |

0.013 |

0.348 |

0.148 |

0.209 |

||||||

|

Gender |

Male Female |

74(41.5%) 64(34.7%) |

104(58.4%) 120(65.2%) |

76(42.6%) 78(42.3%) |

102(57.3%) 106(57.6%) |

19(10.6%) 27(14.6%) |

159(89.3%) 157(85.3%) |

34(19.1%) 62(33.6%) |

144(80.8%) 122(66.3%) |

30(16.8%) 46(25%) |

148(83.1%) 138(75%) |

|

P-Value |

0.184 |

0.953 |

0.162 |

0.002 |

0.057 |

||||||

|

Residency |

Rural Urban |

77(67.5%) 61(24.5%) |

37(32.4%) 187(75.4%) |

40(35.1%) 114(45.9%)

|

74(64.9%) 134(54.1%) |

11(9.64%) 35(14.1%) |

103(90.3%) 213(85.8%) |

16(14.1%) 80(32.2%) |

98(85.9%) 168(67.7%) |

12(10.5%) 64(25.8%) |

102(89.4%) 184(74.2%) |

|

P-Value |

<0.001 |

0.052 |

0.236 |

<0.001 |

0.001 |

||||||

|

Education |

Masters or above Graduate Intermediate Matric/Middle Primary/Illiterate |

11(13.9%) 14(15.2%) 37(40.6%) 34(60.7%) 42(95.4%) |

68(86.1%) 78(84.7%) 54(59.3%) 22(39.3%) 2(4.54%) |

42(53.16%) 30(32.6%) 47(51.6%) 22(39.3%) 13(29.5%) |

37(46.8%) 62(67.3%) 44(48.3%) 34(60.7%) 31(70.4%) |

6(7.59%) 17(18.4%) 13(14.3%) 8(14.4%) 2(4.54%) |

73(92.4%) 75(81.5%) 78(85.7%) 48(85.7%) 42(95.4%) |

28(35.4%) 27(29.3%) 30(32.9%) 6(10.7%) 5(11.4%) |

51(64.5%) 65(70.7%) 61(67.1%) 50(89.3%) 39(88.6%) |

31(39.2%) 17(18.4%) 15(16.4%) 9(16.1%) 4(9.09%) |

48(60.8%) 75(81.5%) 76(83.5%) 47(83.9%) 40(90.9%) |

|

P-value |

<0.001 |

0.008 |

0.108 |

0.001 |

<0.001 |

||||||

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrates the knowledge and barriers to contact lens usage among respondents who visited Al-Shifa Trust Eye Hospital, Rawalpindi, Pakistan. An individual’s health behavior can be determined by assessing his/her knowledge and health education is considered an effective tool to promote health.In general, 68% of participants were aware of contact lenses, with 50.8% understanding their dual purpose for both cosmetic and correction needs. Notably, females exhibited a higher knowledge level (63.6%) about contact lenses compared to males.

Our findings deviate from a 2018 study in Karachi, Pakistan,15 where all participants demonstrated substantial knowledge about contact lenses. In contrast, a 2017 study in Ghana revealed lower awareness, particularly among the younger adult population, regarding the use of contact lenses as a vision correction method.4Similarly in our study,76% of participants were from the age group 21-30 and amongst them, 90% of students had good knowledge about contact lens. This divergence could be attributed to the heightened self-consciousness among young adults, who often seek greater social acceptance without wearing glasses. A parallel observation was made in a 2015 study, which suggested that young adults frequently opt for contact lenses to improve their physical appearance.16

Our study identified a direct correlation between participants' socioeconomic backgrounds and their knowledge of contact lens usage. Specifically, 75% of participants with a normal socioeconomic history exhibited poor knowledge, whereas 73% with a good socioeconomic history and 89% with an excellent socioeconomic history demonstrated good knowledge in this regard. Similarly, the residency of participants also affects the level of knowledge, as 71% from the urban area showed good knowledge regarding contact lens use. Our results were consistent with a study conducted in Ghana, in 2017, which indicated that populations with low-income settings reported inadequate knowledge about contact lens usage.4Another study conducted in Nigeria, in 2014 also reported that 45.8% of spectacle wearers were aware of contact lenses as an alternative to spectacles.11Poor contact lens awareness was also noted in an Iranian study in 2013. This study was conducted in similar socioeconomic settings in Africa.13Another study in 2013, conducted in rural central India, reported that only about half of the study population (non-spectacle wearers) knew about the contact lenses to be used for correction purposes.17All these results were consistent with our study. Socioeconomic status, education, and residential areas are interconnected factors that directly influence knowledge about contact lens usage. The majority of our respondents were from a good socioeconomic background, urban areas, and possessed high levels of education, contributing to substantial knowledge about various aspects of contact lens usage. However, despite this good knowledge, the barriers to contact lens wear also raised concerns.

By investigating the possible barriers towards contact lens use for spectacle users, lack of interest and knowledge, difficulty in insertion and removal, and also the fear of side effects is considered to be the major barriers that hinder spectacle users from agreeingupon the use of contact lenses. The other barriers found were care and maintenance problems, negative advice, durability, satisfaction with spectacles, and fear of foreign body sensations. Contrary to our study, a multi-center survey conducted in Italy by Zeri F et al, in 2014, revealed that care of contact lenses and fear of eye infections were the weak barriers towards contact lens use among ammetropes,5while Thite N et al, in 2015noted insufficient knowledge and cost as a major barrier from patient’s point of view and Berry S et al, in 2013gave negative response for ease of its use.18,19 Gupta N and Naroo SA also concluded the same findings.20So, this study along with the previous studies discussed above, share the common point that one of the major barriers to the usage of contact lenses is an inconvenience.

The study revealed several significant associations between demographic variables and barriers to contact lens use. Older age and rural residency were linked to a lack of knowledge about contact lenses. Gender, particularly among females, showed a significant association with the fear of side effects. Socioeconomic status and occupation were notably associated with satisfaction with glasses, with economic pressures in developing countries like Pakistan hindering consideration of alternatives to spectacles. Lack of interest, fear of side effects, and satisfaction with spectacles were found to be associated with higher levels of education, indicating that education plays a crucial role in shaping perceptions and preferences. This study, possibly one of the first in this context, sheds light on the intricate relationship between demographic variables of spectacle users and barriers to contact lens use.

Our study faced limitations, including a small sample size, a brief study duration, limited resources, and an uneven distribution of participants between urban and rural areas due to COVID-19 lockdowns. For future research, we recommend conducting studies on a larger scale with larger sample sizes. Community awareness and educational programs are advised to inform individuals about proper contact lens care, usage guidelines, and behaviors that may pose risks leading to eye infections in contact lens users. It is also recommended to establish a support system for individuals encountering difficulties with the wearing procedure, offering trials and addressing any ambiguities. To gauge the impact of these initiatives, a survey could be conducted after removing barriers and educating people about the correct process of contact lens use, identifying how many spectacle wearers would consider transitioning to contact lenses.

CONCLUSION

In summary, our findings indicate that individuals possess fundamental knowledge about contact lenses but lack awareness regarding their usage, handling, care, maintenance, lens case, and solutions. The primary barriers identified among spectacle wearers include a lack of interest and specific knowledge, while cost, the absence of service providers, and parental restrictions were comparatively weaker barriers to contact lens use. Notably, younger individuals, students, unmarried individuals, and those residing in urban areas exhibited greater awareness of contact lens use and associated barriers. To address these challenges, educating the public about contact lenses and conducting experimental trials for visual performance on potential candidates emerge as potential strategies to mitigate barriers to wearing contact lenses.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We cordially acknowledge the management and staff of Al-Shifa trust eye Hospital for their cooperation to conduct this study.

REFERENCES:

1. Tchiakpe MP, Nhyira SA, Nartey A. Awareness and response of undergraduate spectacle wearers to contact lens usage. J Clin Ophthalmol Optom [Internet]. 2017;1(1):7.

2. Benjamin WJ, Borish IM. Correction of presbyopia with contact lenses. In: Benjamin WJ, Borish IM (eds). Borish’s Clinical Refraction(Second Edition), Butterworth-Heinemann, 2006, pp 1274-1319.ISBN 9780750675246. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-7524-6.50033-8

3. Khurana AK. Theory and Practice of Optics & Refraction. (Fourth Edition) E-Book 2017. Elsevier India. ISBN 9788131249703https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/39024756-theory-and-practice-of-optics-refraction---e-book

4. Abokyi S, Manuh G, Otchere H, Ilechie A. Knowledge, usage and barriers associated with contact lens wear in Ghana. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2017;40(5):329-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2017.05.006

5. Cope JR, Collier SA, Rao MM, Chalmers R, Mitchell GL, Richdale K, et al. Contact lens wearer demographics and risk behaviors for contact lens-related eye infections—United States, 2014. MMWR MorbMortal Wkly Rep 2015;64(32):865-70. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6432a2

6. Kerr C, Ruston D. The ACLM contact lens year book; 2012. [Accessed on: January 30, 2021]. Available from URL:https://www.bcla.org.uk/Public/Member_Resources/Free_Discounted_Publications/ACLM_Contact_Lens_Year_Book/Public/Member_Resources/ACLM_Contact_Lens_Year_Book.aspx?hkey=31d61240-62f2-43d5-85e5-0b5aae68342a

7. Abahussin M, AlAnazi M, Ogbuehi KC, Osuagwu UL. Prevalence, use and sale of contact lenses in Saudi Arabia: Survey on university women and non-ophthalmic stores. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2014;37(3):185–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2013.10.001

8. Uchino M, Dogru M, Uchino Y, Fukagawa K, Shimmura S, Takebayashi T, et al. Japan ministry of health study on prevalence of dry eye disease among Japanese high school students. Am J Ophthalmol 2008;146(6):925-9.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2008.06.030

9. Ibanga AA, Nkanga DG, Etim BA, IC Echieh. Awareness of the practice and uses of contact lens amongst students in a Nigerian tertiary institution. Sch J Appl Med Sci 2017;5(8B):3111–6.

10. Ky W, Scherick K, Stenson S . Clinical survey of lens care in contact lens patients. CLAO J1998;24(4):216-9.

11. de Oliveira PR, Temporini-Nastari ER, Alves MR, Kara-José N. Self-evaluation of contact lens wearing and care by college students and health care workers. Eye Cont Lens 2003;29(3):164–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.icl.0000072829.76899.b5

12. Ayanniyi AA, Olatunji FO, Hassan RY, Adekoya BJ, Monsudi KF, Jamda AM. Awareness and attitude of spectacle wearers to alternatives to corrective eyeglasses. Asian J Ophthalmol 2014;13(3):86-94. https://doi.org/10.35119/asjoo.v13i3.130

13. Ranjbar SMAK , Pourmazar R, Gohary I. Awareness and attitude toward refractive error correction methods: a population based study in Mashhad.Patient Saf Qual Improve J 2013;1(1):23-9.

14. Bui TH, Cavanagh HD, Robertson DM. Patient compliance during contact lens wear: Perceptions, awareness, and behavior. Eye Cont Lens 2010;36(6):334-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/icl.0b013e3181f579f7

15. Irfan R, Memon RS, Shaikh MY, Khalid I, Shakeel N, Tariq E. Knowledge and attitude of youth towards contact lenses in Karachi, Pakistan. J Glob Heal Reports 2019;3:e2019042. https://doi.org/10.29392/joghr.3.e2019042

16. Plowright AJ, Maldonado-Codina C, Howarth GF, Kern J, Morgan PB. Daily disposable contact lenses versus spectacles in teenagers. Optom Vis Sci 2015;92(1):44–52. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000454

17. Agarwal R, Dhoble P. Study of the knowledge, attitude and practices of refractive error with emphasis on spectacle usages in students of rural central India. J Biomed Pharm Res 2013;2(3):150-4.

18. Naroo SA, Shah S, Kapoor R. Factors that influence patient choice of contact lens or photorefractive keratectomy. J Refract Surg 1999;15(2):132-6.https://doi.org/10.3928/1081-597x-19990301-09

19. Thite N, Naroo S, Morgan P, Shinde L, Jayanna K, Boshart B. Motivators and barriers for contact lens recommendation and wear. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2015; 38(Suppl 1):E41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2014.11.069

20. Gupta N, Naroo SA. Factors influencing patient choice of refractive surgery or contact lenses and choice of centre. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2006;29(1):17–23.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2005.10.006

|

Following author have made substantial contributions to the manuscript as under:

UeA, MS: Concept and study design, acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript, approval of the final version to be published

FA & KNA: Analysis and interpretation of data, critical review, approval of the final version to be published

Author agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. |

|

CONFLICT OF INTEREST Authors declared no conflict of interest, whether financial or otherwise, that could influence the integrity, objectivity, or validity of their research work.

GRANT SUPPORT AND FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE Authors declared no specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors |

|

DATA SHARING STATEMENT The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request |

|

|

|

KMUJ web address: www.kmuj.kmu.edu.pk Email address: kmuj@kmu.edu.pk |