![]() https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2025.23320

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2025.23320

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Development and Validation of the Urdu-language Borderline Personality Disorder Scale for Adults: A Psychometric Analysis

Samia Rashid ![]() 1, 2,

Zaqia Bano

1, 2,

Zaqia Bano ![]() 2, 3

2, 3

|

1: Department of Psychology, University of Gujrat, Gujrat, Pakistan 2: Department of Psychology, National University of Medical Sciences, Rawalpindi, Pakistan 3: Department of Clinical Psychology, NUR International University, Lahore, Pakistan

Email

Contact #: +92-347- 6681017

Date Submitted: February 07, 2023 Date Revised: June 16, 2024 Date Accepted: July 03, 2024 |

|

THIS ARTICLE MAY BE CITED AS: Rashid S, Bano Z. Development and Validation of the Urdu-language Borderline Personality Disorder Scale for Adults: A Psychometric Analysis. Khyber Med Univ J 2025;17(Suppl 1):S37-S45. https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2025.23320 |

ABSTRACT

Objective: To develop and validate an Indigenous Borderline Personality Disorder Scale (BDPDS) for adults in Urdu, tailored to the cultural and linguistic context of Pakistan.

Methods: The cross-sectional analytical study was conducted from February 15 to June 20, 2019, on 234 adults (123 males, 111 females) aged 19 and above, recruited through purposive sampling. Study was approved by Departmental Research Review Committee, University of Gujrat, Pakistan. The scale was developed using established guidelines, beginning with an 81-item pool derived from literature, diagnostic criteria, and expert input. Pilot testing with 100 participants refined the pool to 79 items. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) identified seven factors, and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) validated the model, leading to a final 32-item scale. Psychometric properties were evaluated using Cronbach's alpha for reliability and Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD) for convergent validity.

Results: EFA revealed a seven-factor structure explaining significant variance, with factor loadings ranging from 0.40 to 0.82. CFA confirmed the model fit with a CFI of 0.919 and RMSEA of 0.059. The BDPDS demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.949) and high reliability across subscales (α = 0.747–0.888). Convergent validity was established with a significant correlation (r = 0.579, p < 0.01) with ZAN-BPD.

Conclusion: The 32-item BDPDS is a psychometrically robust and culturally sensitive tool for assessing borderline personality disorder in Urdu-speaking adults. Its reliability and validity make it suitable for clinical and research applications, offering a consistent measure for understanding and addressing borderline personality traits.

Keywords: Borderline Personality Disorder (MeSH); Scale development (Non-MeSH); Psychometric properties (Non-MeSH); Psychometric (MeSH); Factor Analysis, Statistical (MeSH).

INTRODUCTION

Personality is a unique set of behaviors that individuals adopt in response to dynamic internal and external factors. It is a complex combination of developmental, psychological, social, and biological elements, and even among those diagnosed with personality disorders, each individual possesses a distinct personality. Interpersonal relationships are fundamental to normal social living, contributing to healthier and more fulfilling lives. Conversely, unstable and unbalanced relationships-whether marked by isolation or excessive dependency-can lead to dissatisfaction, frustration, and discontent. While interpersonal relationships may naturally vary, excessive instability in emotions, thoughts, mood, and behavior can hinder psychological well-being and daily functioning. Emotional balance plays a critical role in regulating emotions during challenging times and enhancing psychological health. In contrast, emotional dysregulation leads to impaired functioning in everyday life.1

Borderline personality disorder (BPD), is characterized by persistent behavioral patterns involving a disturbed self-image, mood fluctuations, unstable interpersonal relationships marked by idealization or devaluation, temper outbursts, depersonalization under extreme stress, and self-destructive behaviors, excluding suicidal attempts. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), BPD is diagnosed when five or more of its nine criteria are met, with symptoms becoming clear and persistent by age 18 years.2 Various risk factors are associated with BPD, including low socioeconomic status, childhood abuse, parental divorce or loss, job stress, and childhood trauma.3,4

The prevalence of BPD has been estimated at 1.6% to 5.9%, with specific variations reported among Native American men, Hispanic men and women, and Asian women.5 It is more prevalent in females (approximately 75%) than in males, and its severity tends to decrease with age. Instability in relationships is more prominent in early adulthood but stabilizes by the 30s or 40s. BPD may originate from a combination of genetic, environmental, and hereditary factors, including first-degree relatives.6 Numerous studies have explored the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and borderline personality disorder, examining the severity of the abuse and whether it involved infiltration, revealing a significant association between the two.7 However, childhood sexual abuse does not always result in borderline personality disorder; instead, it may lead to other conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder. Proximity seeking remains one of the most critical features of borderline personality disorder. Some overlapping features, such as self-mutilating behaviors-including cutting, burning, or harming-are common in both BPD and post-traumatic conditions.8

Addressing psychological issues requires the development of reliable and culturally appropriate assessment tools. Personality has long been a focus for psychologists, clinicians, psychiatrists, and researchers, with numerous theories and models addressing personality disorders. Literature highlights the richness of assessment tools for personality disorders across different cultures.9 However, while many theories and assessment measures exist globally, there remains a scarcity of culturally appropriate indigenous tools for measuring BPD in adults in Pakistan.

Existing tools, such as the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD),10 the Borderline Evaluation of Severity over Time (BEST),11 and the Borderline Personality Traits Scale (BPTS),12 are primarily developed in English, reflecting Western cultural norms. When these tools are applied in culturally distinct populations, issues such as language barriers and cultural biases may result in inaccurate assessments.13 Cultural differences are often overlooked, leading to potential misinterpretations when tests are administered outside their original context. Thus, the need arises for a measure that eliminates language and cultural barriers while being accessible and reliable for diverse populations in Pakistan.

The primary aim of the current study was to develop and validate an indigenous, culturally appropriate, and self-report measure for assessing borderline personality disorder among adults in Urdu language.

METHODS

Phase I: Development of an indigenous Borderline personality disorder scale: The study was approved by the Departmental Research Review Committee of the Department of Psychology, University of Gujrat, Pakistan, to ensure ethical compliance. It was conducted between February 15, 2019, and June 20, 2019. A cross-sectional analytical study design was employed, and data were collected from various government and private colleges, universities, hospitals, and communities in Gujrat, Pakistan.

Participants included adults aged 19 years and above, of both genders. Individuals under 19 years of age and psychiatric patients were excluded. A purposive sampling technique was adopted due to time constraints. Initially, rapport was established with participants by providing an introduction, affiliation details, and an explanation of the research objectives. Participants were assured of the anonymity and confidentiality of their information. Both oral and written consent were obtained, and only willing individuals participated in the study.

Data collection was conducted using a self-reported questionnaire. Participants received detailed instructions on how to read the items carefully and select the most appropriate responses. Their answers were recorded directly on the questionnaire. Developing a scale involves creating a reliable and valid measure to assess a construct of interest.14 The first phase of the study focused on developing a Borderline Personality Disorder Scale in Urdu, the national language of Pakistan. Standardized procedures for scale construction were followed.15

Initially, items were generated using a Likert Rating Scale with ordinal-level measurements, arranged sequentially from weaker to stronger terms.16 An item pool was created based on the symptoms of the construct, literature, and diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder, aimed at assessing personality disorders among adults. A selected-response, multiple-choice format was used to design the questionnaire.

The item pool consisted of 81 statements, including both positive and negative items, reflecting individual thoughts, behaviors, and interpersonal relationships. This initial draft was subjected to content validation by subject-matter experts.17 As DeVellis18 highlights, expert panel reviews are crucial for finalizing the item pool. Based on expert feedback, items were modified, added, retained, or discarded as needed. Following thorough analysis, 79 items were retained for data collection.

Pilot testing was conducted to evaluate user-friendliness and item clarity, identifying any potential issues to ensure smooth progression in future studies.19 The tryout draft was administered to 100 adult participants aged 18 and above, comprising both males and females, recruited from the general community. This process assessed the clarity and relevance of the items. Subsequently, a sample of 234 adults (Male = 123, Female = 111) was recruited from the community, university professionals, faculty, students, and healthcare institutions, including hospitals.

After administering the scale, correlation analysis, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were performed. Items with correlation values below 0.4 were discarded, leaving a total of 57 items.

Cohen and Swerdlik15 define validity as "the degree to which a construct measures what it is intended to measure." Validity assessment is a critical step in evaluating a test's psychometric properties. Validity ensures the inferences drawn from the test are accurate. The convergent validity of the Borderline Personality Disorder Scale was evaluated using the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD).10

RESULTS

Table I: Inter-item correlation of 57 items of Borderline personality disorder (n=234)

|

Sr. No. |

Item No. |

R |

Sr. No. |

Item No. |

R |

|

1 |

1 |

.606** |

30 |

36 |

.636** |

|

2 |

2 |

.531** |

31 |

37 |

.588** |

|

3 |

3 |

.468** |

32 |

38 |

.651** |

|

4 |

4 |

.567** |

33 |

39 |

.601** |

|

5 |

5 |

.555** |

34 |

40 |

.612** |

|

6 |

6 |

.496** |

35 |

41 |

.490** |

|

7 |

7 |

.572** |

36 |

42 |

.656** |

|

8 |

8 |

.519** |

37 |

43 |

.573** |

|

9 |

9 |

.498** |

38 |

44 |

.589** |

|

10 |

10 |

.505** |

39 |

46 |

.512** |

|

11 |

11 |

.498** |

40 |

48 |

.400** |

|

12 |

13 |

.504** |

41 |

51 |

.517** |

|

13 |

14 |

.591** |

42 |

52 |

.432** |

|

14 |

15 |

.518** |

43 |

53 |

.664** |

|

15 |

16 |

.494** |

44 |

58 |

.469** |

|

16 |

17 |

.413** |

45 |

59 |

.472** |

|

17 |

18 |

.595** |

46 |

62 |

.581** |

|

18 |

19 |

.487** |

47 |

63 |

.498** |

|

19 |

25 |

.430** |

48 |

64 |

.457** |

|

20 |

26 |

.461** |

49 |

65 |

.424** |

|

21 |

27 |

.546** |

50 |

67 |

.471** |

|

22 |

28 |

.588** |

51 |

70 |

.443** |

|

23 |

29 |

.493** |

52 |

72 |

.643** |

|

24 |

30 |

.531** |

53 |

73 |

.499** |

|

25 |

31 |

.536** |

54 |

75 |

.521** |

|

26 |

32 |

.665** |

55 |

76 |

.422** |

|

27 |

33 |

.448** |

56 |

77 |

.677** |

|

28 |

34 |

.590** |

57 |

78 |

497 |

|

29 |

35 |

.592** |

|

|

|

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

In Table I, the correlation coefficient values ware suppressed to 0.40 and literature suggests that the value 0.40 or above is considered as appropriate.20

Table II: Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (n=234)

|

Variable |

KMO |

Bartlett’s Test |

||

|

Chi-Square |

Df |

Sig |

||

|

Borderline Personality Disorder Scale (BPDS) |

.939 |

10484.139 |

1596 |

.000 |

Table II shows the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy i.e., .9 and significant (p<.001) Bartlett’s test of sphericity.

Table III: Factor loading of 57 item on Borderline personality disorder

scale after varimax rotation (n=234)

|

Sr. No. |

Item No. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

1 |

21 |

.659 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

22 |

.709 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

24 |

.638 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

25 |

.686 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

26 |

.664 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

27 |

.620 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

28 |

.452 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

30 |

.498 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

32 |

.436 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

33 |

.560 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

34 |

.491 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

36 |

.536 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13 |

39 |

.584 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

40 |

.456 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15 |

9 |

|

.599 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

16 |

10 |

|

.592 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

17 |

11 |

|

.632 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

18 |

12 |

|

.434 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

19 |

13 |

|

.654 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

14 |

|

.536 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

21 |

15 |

|

.639 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

22 |

16 |

|

.729 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

23 |

18 |

|

.655 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

24 |

19 |

|

.673 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

25 |

20 |

|

.482 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

26 |

44 |

|

|

.706 |

|

|

|

|

|

27 |

45 |

|

|

.516 |

|

|

|

|

|

28 |

46 |

|

|

.712 |

|

|

|

|

|

29 |

47 |

|

|

.795 |

|

|

|

|

|

30 |

48 |

|

|

.821 |

|

|

|

|

|

31 |

49 |

|

|

.811 |

|

|

|

|

|

32 |

50 |

|

|

.758 |

|

|

|

|

|

33 |

51 |

|

|

.605 |

|

|

|

|

|

34 |

1 |

|

|

|

.476 |

|

|

|

|

35 |

2 |

|

|

|

.720 |

|

|

|

|

36 |

3 |

|

|

|

.756 |

|

|

|

|

37 |

4 |

|

|

|

.674 |

|

|

|

|

38 |

5 |

|

|

|

.549 |

|

|

|

|

39 |

6 |

|

|

|

.748 |

|

|

|

|

40 |

7 |

|

|

|

.706 |

|

|

|

|

41 |

23 |

|

|

|

.467 |

|

|

|

|

42 |

31 |

|

|

|

.453 |

|

|

|

|

43 |

35 |

|

|

|

|

.486 |

|

|

|

44 |

38 |

|

|

|

|

.451 |

|

|

|

45 |

41 |

|

|

|

|

.557 |

|

|

|

46 |

42 |

|

|

|

|

.607 |

|

|

|

47 |

43 |

|

|

|

|

.458 |

|

|

|

48 |

52 |

|

|

|

|

|

.550 |

|

|

49 |

53 |

|

|

|

|

|

.516 |

|

|

50 |

54 |

|

|

|

|

|

.443 |

|

|

51 |

55 |

|

|

|

|

|

.699 |

|

|

52 |

56 |

|

|

|

|

|

.608 |

|

|

53 |

57 |

|

|

|

|

|

.529 |

|

|

54 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.454 |

|

55 |

17 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.410 |

|

56 |

29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.558 |

|

57 |

37 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.539 |

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis; Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization; Note: (Values<.4 are suppressed)

Exploratory factor analysis expressed seven factors and items with factor stuffing lower than .4 were eliminated, and values of the questions ranged from .40 to .82 were retained (Table III).

Table IV: Model fit summary of confirmatory factor analysis (n=234)

|

P Value |

CMIN/DF |

GFI |

AGFI |

CFI |

RMSEA |

RMR |

|

.000 |

1.809 |

.835 |

.802 |

.919 |

.059 |

.060 |

CMIN/DF: chi-square minimum/degree of freedom; GFI: Goodness of Fit Index; CFI: Comparative Fit Index, AGFI: Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index; RMSEA: Root Mean Square of Error Approximation

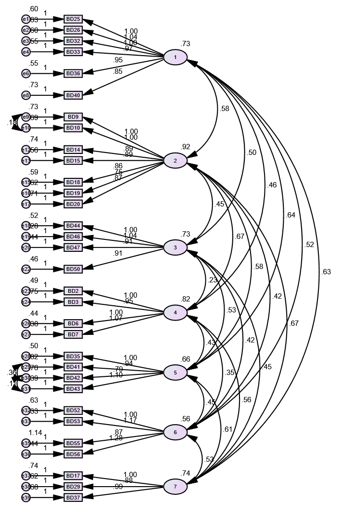

Table IV figure out the confirmatory factor analysis for borderline personality and illustrated with seven domains. Deleted items included 1, 4, 5, 8, 11, 12, 13, 16, 21, 22, 23, 24, 27, 28, 30, 31, 34, 38, 39, 45, 48, 49, 51, 54, and 57.

The value of Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was .919 which is suggesting that model of goodness of fit is absolute fit and significant <0.001 (Table IV). The value of CFA above 0.90 is considered as appropriate. Results confirmed the model fit of the scale for borderline personality disorder.21

Figure 1: Confirmatory factor analysis of Borderline Personality Disorder Scale

Confirmatory factor analysis resulted in 32 item Borderline Personality Disorder Scale for Adults.

Phase II: Determination of psychometric properties of borderline personality disorder scale

a) Determination of psychometric properties of borderline personality disorder

The reliability of the scale was .949 whereas, the appropriate reliability limit is 0.70 and above as per literature. The reliability of the borderline personality disorder scale was above the stated limit i.e., .949 (Table V).

Table V: Cronbach alpha of Borderline personality disorder scale (n=234)

|

Scale |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

Number of Items |

Sig |

|

Borderline Personality Disorder Scale (BPDS) |

.949 |

32 |

.000 |

Table VI: Cronbach alpha of subscales of Borderline personality disorder scale (n=234)

|

Subscales |

Item numbers |

Cronbach Alpha |

|

1. Fear of abandonment |

1-6 |

.870 |

|

2. Intense anger |

7-13 |

.888 |

|

3. Self-mutilating behaviour |

14-17 |

.863 |

|

4. Affective instability |

18-21 |

.866 |

|

5. Impulsivity |

22-25 |

.830 |

|

6. Depersonalization |

26-29 |

.800 |

|

7. Emptiness |

30-32 |

.747 |

Note: ** P<.01

Table VI revealed that the reliability of the sub-scales which is also above the prescribed limit.22 The reliability of all the subscale is significantly high which depicted that this is a consistent measure to assess the borderline personality disorder in adults.

b) Construct validity of borderline personality disorders scale

ZAN-BPD is a standardized, diagnostic, and empirically valid 10-item self-report instrument which is used to assess the borderline personality disorder and its severity over time. The convergent validity of the borderline personality disorder scale with the well-developed ZAN-BPD was conducted and resultant value is .579 which is a significant value (Table VII).

Scales (English & Urdu versions) used in this study are given as Annexures (Appendix 1 & 2).

Table VII: Validity analysis of borderline personality disorder scale (n=45)

|

Scales |

1 |

2 |

|

1. BD |

- |

|

|

2. ZAN-BPD |

.579** |

- |

|

Note: p<.01

|

|

|

DISCUSSION

The primary objective of this study was to develop and validate an indigenous Borderline Personality Disorder scale in the national language of Pakistan, Urdu, to address the cultural and language barriers present in existing international assessment tools. The results from the scale development process indicated that the newly developed scale demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including high reliability and validity. After rigorous item generation, expert reviews, pilot testing, and factor analyses, a final set of 57 items was retained for the scale. The convergent validity of the scale was established through comparison with the well-established Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder, showing a significant positive correlation ((r = 0.579, p < 0.01). These findings confirm that the newly developed Urdu version of the BPD scale is a reliable and valid tool for assessing borderline personality traits among Pakistani adults, offering a culturally appropriate alternative to Western-developed measures.

The mental health illness known as borderline personality disorder (BPD) is typified by pronounced impulsivity along with persistent patterns of instability in mood, self-image, and interpersonal relationships. Persistent emotions of emptiness and fear of abandonment add to the disorder's complexity. People who suffer from borderline personality disorder (BPD) frequently experience strong, fast-changing emotions, struggle to control them, and act impulsively, sometimes harming themselves or considering suicide. People with borderline personality disorder (BPD) have difficulties in their interpersonal and professional relationships. They also use medical services frequently and are difficult to cure. Some people experience brief psychotic episodes.23

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is an inescapable feeling of insecurity, poor interpersonal relations, low self-view as well as low motivational control.24 It is connected with high suicidal rate and co-occurring psychiatric clutters, focused treatment application and high expenditures to society.25 Exploratory Factor execution on Borderline disorder expressed seven dimensions having none of the item below .4 value. Seven factors explored by executing EFA. There are actually 9 symptoms that mentioned in DSM-V diagnostic criteria. Although just seven factors explored but, they enclosed wonderfully nine criterions by merging “affective instability and intensive anger” into single class, similarly “identity disruptions and depersonalization” into another single group. Other five groups explained each indicator one by one. Out of nine, five or more symptoms must be present for appropriate diagnosis.6 It was conveyed by the results that it has factor loading assortment from .41 to .82, 64.05% variance and significant .939 KMO, 0.6 KMO value considered as acceptable value.26 Adequate KMO value allow to further gone through the confirmatory investigation. It explored and confirmed seven symptoms in accordance to DSM-V. Modification indices like regression weight and covariance were sighted and applied both. To boost up the values 25 questions, mentioned as problematic in regression weight, were discarded and covariance implemented between item 9 and 10, 41 and 42 as well as 42 and 43. Final 32 item self-report measure with adequate fit expressed as CMIN/DF=1.809, GFI=.835, CFI=.919 and RMSAE <.6, as CFI 0.90 to 0.95 and RMSEA <.6 suggested as cut-off value.20 Convergent validity of Borderline Personality Disorder and Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD) (Zanarini et al., 2003)10 was moderate as r = .579** and reliability value was α = .949. Reliability and validity values depict the psychometric soundness of the test. These findings well supported the scale development procedure and may have implication for future research and diagnostic purpose by mental health professionals and researchers. It is a globally occurring personality disorder,27 but has little epidemiological research consideration outside the western world. Coid and colleagues28 reported 0.7% prevalence in British householders by drawing a random sample of 626 members. 0.5% prevalence estimated in American householders.29 Torgersen and colleagues30 stated a prevalence of 0.7% in Norwegian community residents. 5.9% is lifetime prevalence and 1.6% is point prevalence of borderline personality disorder.31 Clinical setting study revealed its 6.4% prevalence in primary care visits, 9.3% in psychiatric outpatients and 20% in psychiatric inpatients. The ratio of females is also greater in clinical population, but in non-clinical setting it is equally prevailing disorder in both males and females.6

Limitations of the study and suggestions

The study has several limitations that should be considered. One of the primary limitations is the smaller sample size of the clinical population compared to the non-clinical group, which may have limited the diversity of responses and affected the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the study relied on a cross-sectional design, which restricts the ability to draw conclusions about causal relationships. Another limitation is the focus on participants from a specific region, which may not fully capture the broader cultural and demographic variations within the country.

To address these limitations, future studies should include a more balanced clinical and non-clinical sample, with adequate representation from clinical populations. Longitudinal studies are needed to explore causal relationships and the stability of borderline personality traits. Expanding the sample to diverse geographic and cultural groups would improve generalizability. Translating and adapting the scale into multiple languages would enhance its global applicability. Further validation with larger, varied clinical samples is essential to refine the scale’s psychometric properties and ensure its reliability across different populations.

CONCLUSION

The 32-item Indigenous Borderline Personality Disorder Scale, consisting of seven subscales, offers a reliable and efficient tool for diagnosing and researching borderline personality disorder in local population. Its development in Urdu provides a significant resource for assessing borderline personality traits in Pakistani adults. The scale has shown strong initial psychometric properties, including reliability and content validity, making it applicable in both clinical and research contexts. This scale holds promise for identifying borderline personality traits across diverse populations. Future research should aim to refine the scale, broaden its clinical utility, and explore its cross-cultural validity to enhance its global applicability.

REFERENCES

1. Biskin RS. The lifetime course of borderline personality disorder. Can J Psychiatry 2015;60(7):303-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371506000702

2. Cailhol L, Gicquel L, Raynaud J-P. Borderline personality disorder. In Rey JM (ed), IACAPAP e-Textbook of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Geneva: International Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions 2015.

3. Stepp SD, Lazarus SA, Byrd AL. A systematic review of risk factors prospectively associated with borderline personality disorder: Taking stock and moving forward. Personal Disord 2016;7(4):316-23. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000186

4. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Baldassarri L, Bosia M, Bellino S. The role of trauma in early onset borderline personality disorder: a biopsychosocial perspective. Front Psychiatry 2021;12:721361. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.721361

5. Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69(4):533-45. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v69n0404

6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013: 663-6 p.

7. Zanarini MC, Yong L, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Marino MF, et al. Severity of reported childhood sexual abuse and its relationship to severity of borderline psychopathology and psychosocial impairment among borderline inpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002;190(6):381-7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-200206000-00006

8. Eppel AB. A psychobiological view of the borderline personality construct. Rev psiquiatr Rio Gd Sul 2005;27(3):262-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81082005000300005

9. Widiger TA, Hines A, Crego C. Evidence-based assessment of personality disorder. Assessment 2024;31(1):191-98. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911231176461

10. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, Boulanger JL, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J. Zanarini rating scale for borderline personality disorder (ZAN-BPD): a continuous measure of DSM-IV borderline psychopathology. J Pers Disord 2003;17(3):233-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/pedi.17.3.233.22147

11. Pfohl B, Blum N, St. John D, McCormick B, Allen J, Black DW. Reliability and validity of the borderline evaluation of severity over time (BEST): a self-rated scale to measure severity and change in persons with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 2009;23(3):281-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2009.23.3.281

12. Butt MG, Mahmood Z, Saleem S. Self-report measure for borderline personality traits in clinical population. J Postgrad Med Inst 2017;31(4):414-9.

13. Swanepoel I, Kruger C. Revisiting validity in cross-cultural psychometric-test development: a systems-informed shift towards qualitative research designs. S Afr J Psychiatr 2017;17(1):10-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v17i1.250

14. Tay L, Jebb A. Scale Development. In Rogelberg S (ed), The SAGE Encyclopaedia of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2017.

15. Cohen RJ, Swerdlik M. Psychological Testing and Assessment: An Introduction to Tests and Measurement. 7th ed. McGraw−Hill: Primis; 2010.

16. Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psychol 1932;22(140):5-55.

17. Miller LA, Lovler RL. Foundations of psychological testing: A practical approach. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc; 2016.

18. DeVellis RF. Scale Development, Theory and Applications. 4th ed. Applied Social Research Methods University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill: USA; 2017.

19. Fraser J, Fahlman D (Willy), Arscott J, Guillot I. Pilot testing for feasibility in a study of student retention and attrition in online undergraduate programs. Int Rev Res Open Dis Learn 2018;19(1):60. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i1.3326

20. Rahn M. Factor analysis: a short introduction, part 5–dropping unimportant variables from your analysis 2018. [Accsessed on: July 20, 2019]. Available from URL: https://www.theanalysisfactor.com/fa ctor-analysis-5/

21. Miller-Carpenter S. Ten steps in scale development and reporting: a guide for researchers. Commun Methods Meas 2018;12(1):25-44.

22. Griethuijsen RALF, Eijck MW, Haste H, Brok PJ, Skinner NC, Mansour N, et al. Global patterns in students’ views of science and interest in science. Res Sci Educ 2014;45(4):581-603. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11165-014-9438-6

23. Chapman J, Jamil RT, Fleisher C, TorricoTJ. Borderline personality disorder. [Accessed on: July 20, 2019]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430883/

24. Leichsenring F, Leibing E. Kruse J, New AS, Leweke F. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet 2011;377(9759):74-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61422-5.

25. Oldham JM. Borderline personality disorder and suicidality. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(1):20-6. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.20

26. Pallant J. SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS. 4th ed. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin; 2013.

27. Pinto A, Eisen JL, Mancebo MC, Rasmussen SA. Obsessive compulsive personality disorder. In, Abramowitz JS, McKay D, Taylor S (eds), Obsessive- compulsive disorder: Subtypes and spectrum conditions. 2008. Elsevier, New York, USA. ISBN: 9780080447018

28. Coid J, Yang M, Tyrer P, Roberts A, Ullrich S. Prevalence and correlates of personality disorder in Great Britain. Br J Psychiatry 2006;188:423-31. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.188.5.423

29. Samuels J, Eaton WW, Bienvenu OJ, Brown CH, Jr Costa PT, Nestadt G. Prevalence and correlates of personality disorders in a community sample. Br J Psychiatry 2002;180:536-42. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.180.6.536

30. Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V. The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58(6):590-6. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.590

31. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan W, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions (NESARC). J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(7):948-58. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v65n0711

|

Following authors have made substantial contributions to the manuscript as under:

SR & ZB: Conception and study design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, critical review, approval of the final version to be published

Authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. |

|

CONFLICT OF INTEREST Authors declared no conflict of interest, whether financial or otherwise, that could influence the integrity, objectivity, or validity of their research work.

GRANT SUPPORT AND FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE Authors declared no specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors |

|

DATA SHARING STATEMENT The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request |

|

|

|

KMUJ web address: www.kmuj.kmu.edu.pk Email address: kmuj@kmu.edu.pk |

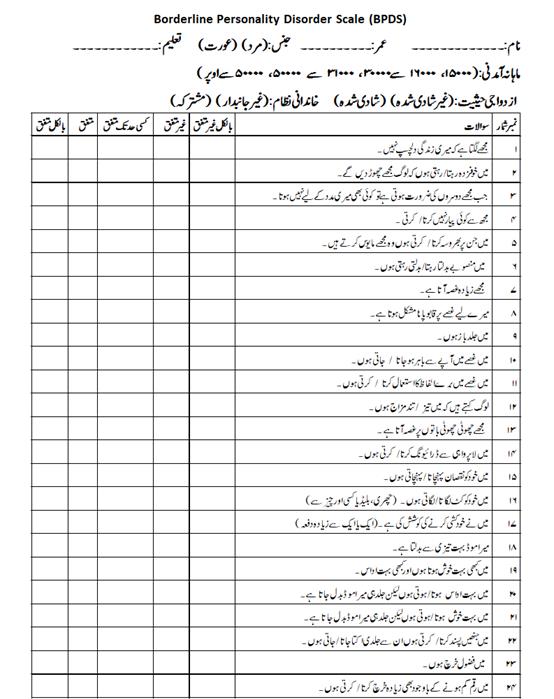

APPENDIX-01

Borderline Personality Disorder Scale

Test Instructions

Item Scoring Format

1 = Strongly Disagree. 2 = Disagree. 3 = To some extent. 4 = Agree. 5 = Strongly Agree.

*No reverse scoring for any item.

|

Subscales |

Item numbers |

Total Items |

|

1 Fear of abandonment |

1-6 |

6 |

|

2 Intense anger |

7-13 |

7 |

|

3 Self-mutilating behavior |

14-17 |

4 |

|

4 Affective instability |

18-21 |

4 |

|

5 Impulsivity |

22-25 |

4 |

|

6 Depersonalization |

26-29 |

4 |

|

7 Emptiness |

30-32 |

3 |

Cutoff Scores

Mild: 64-95

Moderate: 96-127

Severe: 128-160

APPENDIX-02