![]() https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2025.23318 ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2025.23318 ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Development and psychometric validation of an indigenous Urdu-language scale for Paranoid personality disorder in

Pakistani adults

|

1: Department of Psychology, University of Gujrat, Gujrat, Pakistan 2: Department of Psychology, National University of Medical Sciences, Rawalpindi, Pakistan 3: Department of Clinical Psychology, NUR International University, Lahore, Pakistan

Email

Contact #: +92- 347-6681017

Date Submitted: February 07, 2023 Date Revised: February 18, 2024 Date Accepted: March 09, 2024 |

|

THIS ARTICLE MAY BE CITED AS: Rashid S, Bano Z. Development and psychometric validation of an indigenous Urdu-language scale for Paranoid personality disorder in Pakistani adults. Khyber Med Univ J 2025;17(Suppl 1):S3-S11. https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2025.23318 |

ABSTRACT

Objective: To develop and validate an indigenous Urdu-language scale to assess Paranoid Personality Disorder (PPD) in Pakistani adults, addressing the need for culturally appropriate diagnostic tools in mental health.

Methods: This cross-sectional analytical study followed a rigorous scale development process from February to June 2019, including item generation, content validation, pilot testing, and factor analysis. Participants included 234 male and female adults, selected thorough purposive sampling technique from various government and private colleges, universities, hospitals and communities of Gujrat, Pakistan, encompassing both clinical and non-clinical populations. The scale development involved exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis to ensure the reliability and validity of the final 26-item self-report measure.

Results: The PPD Scale demonstrated excellent psychometric properties. The confirmatory factor analysis yielded a Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of .915, indicating good model fit, and a Cronbach's alpha of .934, reflecting high internal consistency. Additionally, the scale showed good convergent validity, with a significant correlation (.641, p<0.01) with the Social Suspiciousness Scale.

Conclusion: The Urdu-language PPD Scale developed in this study is a reliable and valid tool for assessing PPD in Pakistani adults. Its robust psychometric properties, including excellent internal consistency and good model fit, make it a valuable instrument for both clinical and research purposes. The scale’s strong convergent validity further supports its effectiveness in measuring paranoid traits. This culturally appropriate diagnostic tool fills a significant gap in mental health assessments in Pakistan and can aid mental health professionals in diagnosing and understanding PPD within the local context.

Keywords: Personality Disorders (MeSH); Personality disorder assessment (Non-MeSH); Paranoid Personality Disorder (MeSH); Behavior (MeSH); Scale development (Non-MeSH); Reliability (Non-MeSH); Convergent validity (Non-MeSH); Personality (MeSH).

INTRODUCTION

Suspicion is not inherently negative. While it can propel us towards uncovering truths and addressing queries, excessive suspicion may impair mental functioning and social interactions. Historically, Emil Kraepelin first described Paranoid Personality Disorder (PPD) in 1921 as a form of dementia precox, highlighting traits of mistrust and sensitivity.¹ Subsequent distinctions between paranoid and delusional disorders were made by Bleuler in 1906, emphasizing their non-identity.² PPD's association with psychopathic behaviors was further elucidated by Schneider in 1950,³ and since 1952, PPD has been recognized in the DSM, distinguished from schizophrenia and delusional disorder by its specific diagnostic features.

PPD is characterized by pervasive and undue suspiciousness, doubt, and mistrust of others. Individuals with PPD often harbor unfounded doubts about the loyalty or trustworthiness of others, frequently speak ill of others behind their backs, and may misuse or distort information. This disorder can be succinctly described by terms such as "suspiciousness" and "excessive doubts and mistrust." For a clinical diagnosis, at least four out of seven well-defined symptoms must be present. Epidemiological studies indicate its prevalence ranges from 2.3% to 4.4%.⁴ Symptoms typically manifest in childhood and adolescence and may include loneliness, poor peer relationships, social anxiety, underperformance academically, hypersensitivity, unconventional thoughts and speech, and odd fantasies. Such children often appear "anomalous" or "eccentric," attracting mischievous or negative attention. Clinically, PPD is more frequently diagnosed in males than in females and is considered to be influenced both genetically and by socio-cultural factors, particularly in populations such as immigrants and various ethnic or minority groups.⁵

PPD is often mistaken for schizophrenia due to phenomenological similarities such as suspiciousness and paranoid delusions. However, research has demonstrated that these disorders are distinctly different; PPD is notably severe, clinically prevalent but challenging to treat.⁶ Epidemiological data from the United States identify PPD as a significant cause of disability,⁷ a finding supported by Australian epidemiological studies that also highlight PPD's contribution to disability.⁸ In clinical settings, PPD is associated with aggressive behaviors,⁹ and within the forensic domain, it is linked to violent and unlawful acts.¹⁰ While evidence regarding suicidal attempts in PPD remains ambiguous, there is noted comorbidity with depressive and borderline personality disorders, both of which are associated with suicidal ideation and attempts.¹¹

Although the exact cause of PPD is not definitively known, a study conducted with twin adults by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health Twin Panel using the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality suggested that both genetic and environmental factors play roles.¹² Personality disorders have long captured the attention of psychologists, clinicians, psychoanalysts, psychiatrists, and researchers. While these disorders have been extensively studied, the approaches and assessments are often culturally bound. Literature indicates a diversity in the assessment measures for personality disorders across different countries. There is a significant gap in the availability of culturally relevant assessment tools for PPD in Pakistan, particularly those developed in the national language, Urdu, and tailored to the country's unique cultural and linguistic context. Existing scales often fail to account for regional norms, values, and language nuances, limiting their effectiveness and applicability. To address this gap, the current research was aimed to develop and validate an indigenous scale specifically designed for adults in Pakistan. The scale seeks to comprehensively evaluate personality psychopathology by assessing thought patterns, behaviors, relational challenges, and misinterpretations of others' intentions, while adhering to the DSM-5 framework. This effort strives to create a culturally sensitive and linguistically appropriate tool to enhance the understanding and assessment of PPD in the region.

METHODS

The study was approved by Departmental Research Review Committee (DRRC) of Department of Psychology, University of Gujrat, Pakistan for ethical concerns and was conducted from 15th February 2019 to 20th June 2019. The study used cross-sectional analytical study design and the data was collected from different government and private colleges, universities, hospitals and communities of Gujrat, Pakistan. The inclusion criteria was based on age group of adult that were above 19 years and both male and female. People below age 19 and psychiatric patients were excluded from the research. Purposive sampling technique was used for the selection of the participants due to time constraint. Initially, rapport was developed with the participants while giving the introduction, affiliation information and the aim of the research. The respondents were also assured about anonymity and confidentiality of the information. Both oral and written consent was taken from the participants and only willing persons were included in the study. Furthermore, the data collected with self-reported questionnaire. The respondents were given the detailed instructions about how to fill the scale after reading the scale items carefully and select the most appropriate response. The responses of participants were recorded on the questionnaire.

Phase I: Development of an Indigenous Paranoid Personality Disorder Scale: The first phase of study based on the development of paranoid personality disorder scale. An item pool was generated to assess the paranoid personality. The scale was developed in national language (Urdu) of Pakistan. Standard steps for the scale construction followed.13 In the first step Items were generated by using Guttman's facet analysis, ordinal level measurement, and assort sequentially from weaker to stronger terms (Guttman, 1944, 1947).14 Item pool was generated on the basis of symptoms, literature and diagnostic criteria of paranoid personality disorder, for the evaluation of paranoia personality among adults. Selected response format, multiple choice format, used to construct the questionnaire. A pool of 83 items for paranoid personality disorder was generated. These items reflected the individual thoughts, behaviours and interpersonal relationships. The initial draft of the scale was content validated by related subject experts. DeVellis (2017)15 the stage of item pool generation is completed with expert panel item pool reviews. The experts considered each item with respect to its essentiality, appropriateness of material in reference to adults, and construct of paranoid personality disorder. After the vigilant analysis 81 items for paranoid personality disorder were selected. They finalized the 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (for authorization of items at one extreme) all through 5 (for authorization of items at the other extreme) yes absolutely with the exception of reverse items.16 Then try out carried out to check the user appropriateness and understanding about the test to identify potential problem so that the anticipated future study could begin confidently and smoothly.17 The tryout draft was filled from 104 adult individual’s age range 18 and above, both male and female, that recruited from the general community to assess the clarity and relevance of items. Correlation analysis was run on the scale and below .4 values item were discarded. After extraction 45 items were left. In step four factor analysis was administered.

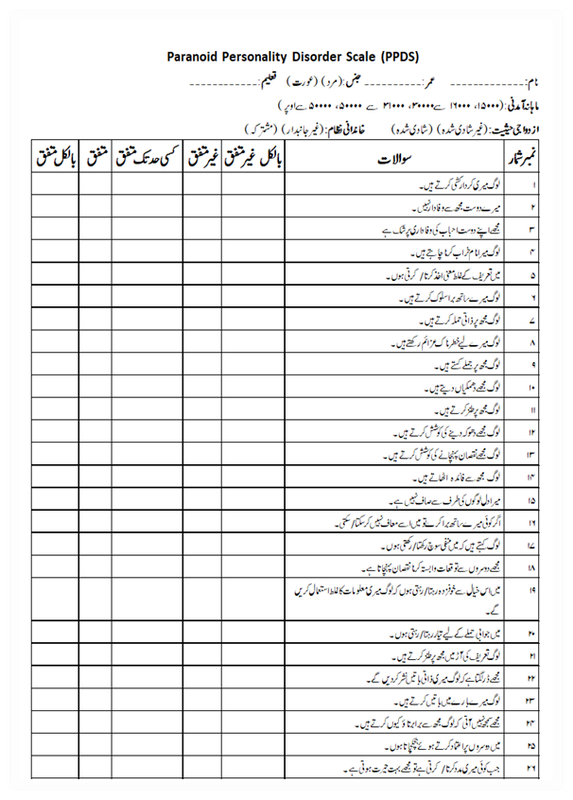

Paranoid Personality Disorder Scale (English & Urdu versions) are given as Annexures (1&2).

RESULTS

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA): The items with less than .4 values were suppressed. Factor loading find the relationship range between factor and item. Factor loading prescribed value is +1 to -1, the extent to which factor loading closer to +1 or -1, there will be higher association among factors. Significant cut-off value for factor loading is .32,18 but literature also supported .3-.4.19 Total eight factors were explored by rotation component matrix (Table I).

Table I: Correlation coefficient of 45 items of Paranoid personality disorder (n=234)

|

Sr. No. |

Item No. |

R |

Sr. No. |

Item No. |

R |

|

1 |

2 |

.553** |

24 |

34 |

.526** |

|

2 |

3 |

.633** |

25 |

35 |

.482** |

|

3 |

4 |

.513** |

26 |

39 |

.538** |

|

4 |

5 |

.428** |

27 |

41 |

.661** |

|

5 |

6 |

.484** |

28 |

42 |

.659** |

|

6 |

7 |

.566** |

29 |

43 |

.704** |

|

7 |

8 |

.483** |

30 |

46 |

.401** |

|

8 |

9 |

.475** |

31 |

47 |

.458** |

|

9 |

10 |

.494** |

32 |

48 |

.637** |

|

10 |

11 |

.670** |

33 |

49 |

.661** |

|

11 |

12 |

.639** |

34 |

50 |

.670** |

|

12 |

13 |

.608** |

35 |

54 |

.482** |

|

13 |

14 |

.614** |

36 |

61 |

.503** |

|

14 |

17 |

.665** |

37 |

62 |

.625** |

|

15 |

19 |

.428** |

38 |

65 |

.572** |

|

16 |

20 |

.450** |

39 |

66 |

.417** |

|

17 |

22 |

.445** |

40 |

71 |

.405** |

|

18 |

23 |

.508** |

41 |

73 |

.483** |

|

19 |

27 |

.631** |

42 |

75 |

.487** |

|

20 |

28 |

.492** |

43 |

77 |

.554** |

|

21 |

29 |

.449** |

44 |

78 |

.444** |

|

22 |

30 |

.576** |

45 |

79 |

.517** |

|

23 |

32 |

.571** |

|

|

|

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Table II shows the results of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was .93, above the normally suggested value of .6, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p<.001).

Table II: Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (n=234)

|

Variable |

KMO |

Bartlett’s Test |

||

|

Chi-Square |

Df |

Sig |

||

|

Paranoid Personality Disorder Scale (PPDS) |

.931 |

6222.561 |

990 |

.000 |

Exploratory factor analysis initially formed 8 factors which explain 62.35% variance. Factors with one item were rejected and seven factors left. Items with factor loading below .4 were eliminated, and factor loading ranging from .44 to .72 (Table III).

Exploratory factor analysis findings for paranoid personality disorder are in accordance with the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder accompanying seven symptoms. Response on the six factors i.e., unjustified doubts about friend’s companion’s faithfulness, suspiciousness about other’s thoughts, reluctant to confide, perceive hidden demeaning, bear grudges, and perception of personal attack and counterattack. The factor attacks and counter attacks was the single factor but get separated through scrutiny. The symptom about spousal fidelity was not extracted by exploratory factor analysis. So, this dimension does not fit to the current culture. They hesitate to respond properly on sexual partner related questions.

Table III: Factor loading of 45 item on Paranoid Personality Disorder Scale

after varimax rotation (n=234)

|

Sr. No. |

Item No. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

1 |

5 |

.567 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

6 |

.630 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

11 |

.677 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

12 |

.728 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

19 |

.561 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

22 |

.441 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

30 |

.572 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

35 |

.591 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

44 |

.598 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

14 |

|

.485 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

26 |

|

.541 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

27 |

|

.561 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13 |

28 |

|

.693 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

29 |

|

.717 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15 |

32 |

|

.444 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16 |

33 |

|

.652 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17 |

36 |

|

.580 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18 |

37 |

|

.608 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

19 |

7 |

|

|

.522 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

8 |

|

|

.623 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

21 |

9 |

|

|

.717 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

22 |

13 |

|

|

.492 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

23 |

24 |

|

|

.497 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

24 |

1 |

|

|

|

.628 |

|

|

|

|

|

25 |

2 |

|

|

|

.724 |

|

|

|

|

|

26 |

3 |

|

|

|

.685 |

|

|

|

|

|

27 |

4 |

|

|

|

.607 |

|

|

|

|

|

28 |

10 |

|

|

|

.443 |

|

|

|

|

|

29 |

15 |

|

|

|

|

.577 |

|

|

|

|

30 |

16 |

|

|

|

|

.639 |

|

|

|

|

31 |

21 |

|

|

|

|

.488 |

|

|

|

|

32 |

25 |

|

|

|

|

.492 |

|

|

|

|

33 |

39 |

|

|

|

|

.451 |

|

|

|

|

34 |

41 |

|

|

|

|

.627 |

|

|

|

|

35 |

42 |

|

|

|

|

.492 |

|

|

|

|

36 |

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

.495 |

|

|

|

37 |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

.536 |

|

|

|

38 |

23 |

|

|

|

|

|

.515 |

|

|

|

39 |

34 |

|

|

|

|

|

.519 |

|

|

|

40 |

43 |

|

|

|

|

|

.442 |

|

|

|

41 |

45 |

|

|

|

|

|

.431 |

|

|

|

42 |

17 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.501 |

|

|

43 |

31 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.678 |

|

|

44 |

38 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.501 |

|

|

45 |

40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.720 |

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis; Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization; Note: (Values<.4 are suppressed)

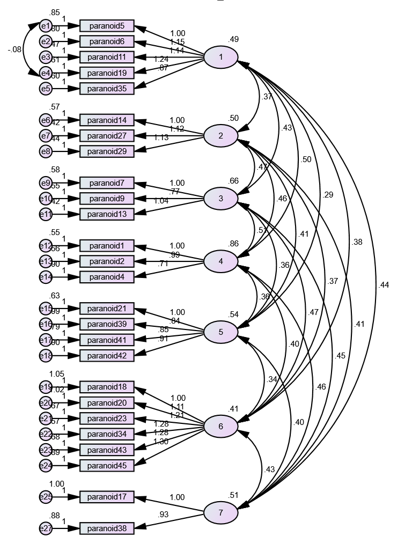

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA): There was total eight factors draw out through EFA, which was further gone through CFA and final seven factors were confirmed with varying number of questions, minimum two and maximum six items in a factor. Worthington and Whittaker (2006)17 indorsed two item factors with high correlation (i.e., r < .70),20 if the sample size is small.21 Studies revealed that 15.8% of the journal articles comprised two-itemed factors in their new measures. Confirmatory factor analysis resulted in 26 item Paranoid Personality Disorder Scale for Adults (Figure 1).

Table IV: Model fit summary of confirmatory factor analysis (n=234)

|

P Value |

CMIN/DF |

GFI |

AGFI |

CFI |

RMSEA |

RMR |

|

.000 |

1.765 |

.864 |

.828 |

.915 |

.057 |

.063 |

CMIN/DF: chi-square minimum/degree of freedom; GFI: Goodness of Fit Index; CFI: Comparative Fit Index, AGFI: Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index; RMSEA: Root Mean Square of Error Approximation, RMR:root mean square residual

In Table IV, the figures of confirmatory factor analysis of Paranoid Personality Disorder Scale for adults depicted with seven factors. Number of items were deleted i.e. 3, 5, 8, 10, 12, 15, 16, 22, 24, 25, 26, 28, 30, 32, 33, 35, 37, 39, and 44. CMIN/DF reflected good fit as value .2 or low considered as good fit,22 preferred23 and should not surpass .3.24 RMSEA less than or equal to ≤ .06 considered as cut-off for a good model fit.25

Phase II: Determination of Psychometric Properties of Paranoid Personality Disorders Scale

a)Cronbach’s alpha reliability: Paranoid Personality Disorder has .93 Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient (Table V and Table VI). A scale or subscale with a greater number of items may have reliability >.7.26 Other studies depicted that .6, .7 and >.70 value considered as acceptable reliability values.27

Table V: Cronbach alpha of Paranoid personality disorder scale (n=234)

|

Scale |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

Number of Items |

Sig |

|

Paranoid Personality Disorder Scale (PPDS) |

.934 |

27 |

.000 |

Table VI: Cronbach alpha of subscales of Paranoid personality disorder scale (n=234)

|

Subscales |

Total items |

Cronbach Alpha |

|

1. Suspiciousness |

5 |

.805 |

|

2. Perceived personal attack |

3 |

.785 |

|

3. Perceived hidden meaning of words |

3 |

.765 |

|

4. Exploiting behaviour |

3 |

.743 |

|

5. Bear grudges |

4 |

.679 |

|

6. Unsuspected suspiciousness |

6 |

.812 |

|

7. Reluctant to confide |

2 |

.501 |

Note: ** p <.01

B) Construct validity of paranoid personality disorder scale: Sample of 45 (N=45) Male=21, Female=24 recruited from colleges and university faculty and students and community population (Table VII). To estimate the convergent validity of Paranoid Personality Disorder Scale, Social Suspiciousness scale (SSS) (Linett, et al., 2019) was selected.28 SSS was designed to evaluate suspiciousness, and associated concepts of anger and hostility, within a social context.

Table VII: Validity analysis of Paranoid personality disorder scale (n = 45)

|

Scales |

1 |

2 |

|

1. Paranoid personality disorder scale |

- |

|

|

2. Social Suspiciousness Scale |

.641** |

- |

Note: ** p<.01

Figure 1: Confirmatory factor analysis of Paranoid Personality Disorder Scale for adults

DISCUSSION

This study developed and validated an indigenous scale for PPD suited to Pakistan's cultural and linguistic context. EFA identified eight factors, refined to seven through CFA, explaining 62.35% of the variance with factor loadings ranging from .44 to .72. Model fit indices (CMIN/DF = 1.765, RMSEA = .057, CFI = .915) confirmed a good fit. The final scale comprised 26 items across seven factors, addressing key PPD symptoms such as unjustified doubts, suspiciousness, reluctance to confide, and grudges. The scale demonstrated high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .93) and construct validity (r = .641, p < .01), establishing its utility for assessing PPD in Pakistan.

Individuals with paranoid personality disorder have persistent feelings of mistrust towards others without sufficient basis, perceive environmental clues negatively, bear grudges, and act in a spiteful manner towards others.29 Pervasive mistrust to other people is a main characteristic of paranoid personality disorder. Moreover, hostility, quarrelsome, and emotional coldness serve as contributing factors.30 The current study is based on the scale development of paranoid personality disorder. There are some scales available to assess this disorder like Paranoid Personality Disorder Features Questionnaire which consists of 23 items and designed to assess six scales like mistrust, hypersensitivity, introversion, antagonism, hyper vigilance and rigidity based on DSM-IV criteria.31 Similarly, Kosson et al. (2008)32 Interpersonal Measure of Schizoid Personality Disorder (IM-SZ) is 12 items measure and used to assess several sides of social interaction (e.g., rapport, absenteeism of artlessness in speech, lack of verbal responsiveness and poor interpersonal hygiene). Furthermore, Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire-Brief (SPQ-B) is precise version of SPQ (74 items). It has three dimensions i.e., cognitive-perceptual deficits, interpersonal deficits and disorganisation, and 22 items. Completion time of this test is just two minutes. This test constructed on the basis of DSM-III-R criteria.33

Although personality assessments are available in larger extent each with the unique concept and entity, but Personality disorders measures in native (Pakistani) language is so limited at the time. So, there was a need to develop a measure that could overcome language, comprehension, and cultural barriers. The current self-report measure is constructed in national language, Urdu, of Pakistan which would be an objective measure, not just for researchers and clinicians but also a layman could report by self. It will assess personality psychopathology and explores the effectiveness of constructing a scale for DSM-5, capturing intensities of impairment in personality functioning.

For scale development, standardized procedure was followed like generation of item pool, content validity, pilot testing, final admistration and factor analysis. In factor analysis step, less than .4 value was suppressed, eight factors explored in rotation component matrix with factor loading ranges from .44 to .72 and 62.35% variance, KMO = .931, 0.6 KMO value considered as acceptable value.34 The factor analysis of the seven-criterion paranoid personality disorder scales resulted in the same composition of the same criteria mentioned in DSM-5. CFA confirmed seven factors, considering modification indices 19 items were rejected and finalizing 26 items likewise, to better fit the model covariance was drawn between item 5 and 19. With every deletion CFA run again until accepted value. CFI = .915; as prescribed 0.90 to 0.95 cut-off value and RMSEA <.6 suggested as cut-off value.24 Model fit indices values of CMIN/DF and RMSEA were satisfactory but to better fit the model CFI modification indices of covariance and regression weights were applied. Problematic questions were observed in regression weight, modification indices, and that Problematic items were discarded. After one-by-one item deletion model estimates were re-calculated until the good CFI value establishment.

In order to evaluate test’s psychometric properties reliability and validity was checked. Inter item reliability of scales and subscales is excellent i.e., α = .934. Construct validity was measured by using social suspiciousness scale (SSS).27 The convergent validity of SSS with Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) was in moderate range i.e., r = .56, p < .0001. Whereas convergent validity of paranoid personality disorder scale with SSS is r = .641** which is strong. Hence, a valid and reliable measure for paranoid personality disorder has been constructed and fulfil the criteria of standardized test construction procedure which would be helpful in both clinical and non-clinical setting.

CONCLUSION

Indigenous paranoid personality disorder scale 26-item scale was developed in native language of Pakistan i.e., Urdu. To evaluate the paranoid personality this is a reliable and efficient measure which can be used by the researcher, psychologist, psychiatrist, social worker and other mental health professionals for research and diagnostic puposes.

1. Kraepelin E. Manic Depressive Insanity and Paranoia. Arno Press, New York,USA. 1921.

2. Bleuler, E. Affectivitat, suggestibilitat, paranoia. Halle: Marhold; 1906.

3. Schneider K, Hamilton M, Anderson E, Thomas C. Psychopathic Personalities. Springfield: Springfield, IL; 1950.

4. Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry 2007;15;62(6):553-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019

5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders. (5th ed. TR). American Psychiatric Publications; Arlington, VA, USA. 2013. ISBN: 978-0890425763.

6. Lee R. Mistrustful and misunderstood: a review of paranoid personality disorder. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep 2017;4(2):151-65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40473-017-0116-7

7. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatr 2004;65:948-58. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v65n0711

8. Loranger AW, Janca A, Sartorius N, Dahl AA, Andreoli A, Reich JH, et al. Assessment and diagnosis of personality disorders: The ICD-10 international personality disorder examination (IPDE). Cambridge University Press & Assessment, Cambridge, UK. 2007. ISBN: 9780521041669

9. Berman ME, Fallon AE, Coccaro EF. The relationship between personality psychopathology and aggressive behavior in research volunteers. J Abnorm Psychol 1998;107(4):651-8. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.107.4.651

10. Mullen PE, Lester G. Vexatious litigants and unusually persistent complainants and petitioners: from querulous paranoia to querulous behaviour. Behav Sci Law 2006;24(3):333-49. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.671

11. Pompili M, Girardi P, Ruberto A, Tatarelli R. Suicide in borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Nord J Psychiatr 2005;59(5):319-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480500320025

12. Kindler KS, Myers J, Torgersen S, Neale MC, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. The heritability of cluster A personality disorders assessed by both personal interview and questionnaire. Psychol Med 2007;37(5):655-65. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291706009755

13. Tay L, Jebb A. Scale Development. In Rogelberg, S (Ed), The SAGE Encyclopaedia of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2017.

14. Guttman LA. A basis for scaling qualitative data. Am Sociol Rev 1944;9(2):139-50. https://doi.org/10.2307/2086306

15. DeVellis RF. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. 4th ed. SAGE Publications, Inc., California, USA; 2017. ISBN: 9781506341569.

16. Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psychol 1932;22(140):155.

17. Fraser J, Fahlman D (Willy), Arscott J Guillot I. Pilot testing for feasibility in a study of student retention and attrition in online undergraduate programs. Int Rev Res Open Dis Learn 2018;19(1):260-78. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i1.3326

18. Worthington RL, Whittaker TA. Scale development research: a content analysis and recommendations for best practices. Couns Psychol 2006;34(6):806-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0011000006288127

19. Miller-Carpenter S. Ten steps in scale development and reporting: a guide for researchers.Commun Methods Meas 2018;12(1):25-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2017.1396583

20. Yong AG, Pearce S. A beginner’s guide to factor analysis: focusing on exploratory factor analysis. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol 2013;9(2):79-94. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.09.2.p079

21. Kline RB. Methodology in the social sciences. In: Little TD (eds), Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd edition). Guilford Press, New York, USA. 2011. ISBN: 978-1-60623-876-9.Ullman JB, Bentler PM. Structural Equation Modeling. In: Weiner I, Schinka JA, Velicer WF (eds) Handbook of Psychology, (2nd ed). John Wiley & Sons, Inc., USA. 2012. ISBN: 9781118133880. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118133880.hop202023

22. Ullman JB, Bentler PM. Structural Equation Modeling. In: Weiner I, Schinka JA, Velicer WF (eds) nd Handbook of Psychology, (2 ed). John Wiley & Sons, Inc., USA. 2012. ISBN: 9781118133880. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118 133880.hop202023

23. Gallagher MW, Brown TA. Introduction to Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling. In: Teo T (eds), Handbook of Quantitative Methods for Educational Research. SensePublishers, Rotterdam. 2013. ISBN: 978-94-6209-404-8 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6209-404-8_14

24. Byrne BM. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS; Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates New Jersey, USA. 2006.

25. Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 1999;6(1):1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

26. Cortina JM. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J Appl Psychol 1993;78(1):98-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98

27. Griethuijsen RALF, Eijck MW, Haste H, Brok PJ, Skinner NC, Mansour N, et al. Global patterns in students’ views of science and interest in science. Res Sci Educ 2014;45(4):581–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-014-9438-6

28. Linett A, Monforton J, MacKenzie M, McCabe RE, Rowa K, Antony MM. The social suspiciousness scale: development, validation, and implications for understanding social anxiety disorder. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2019;41(2):280-93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-019-09724-3

29. Lewis K, Ridenour JM. "Paranoid Personality Disorder." In Zeigler-Hill V, Shackelford TK (eds.), Encyclopedia Personality and Individual Differences. Springer, Cham. New York, USA. 2020. ISBN: 978-3-319-24612-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24612-3_615

30. Bernstein DP, Useda JD. Paranoid personality disorder. In O'Donohue W, Fowler KA, Lilienfeld SO (eds.), Personality disorders: Toward the DSM-V. Sage Publications, Inc. New York, USA. (pp. 41–62) 2007. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483328980.n3

31. Useda JD. The construct validity of the paranoid personality disorder features questionnaire (PPDFQ): a dimensional assessment of paranoid personality disorder. University of Missouri - Columbia (ProQuest Dissertation & Theses), 2001. 3025654. [Accessed on: January 20, 2023]. Available from URL: https://www.proquest.com/openview/46827e8c4d228b1a708fd4a0137ca78c/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

32. Kosson DS, Blackburn R, Byrnes KA, Park S, Logan C, Donnelly JP. Assessing interpersonal aspects of schizoid personality disorder: preliminary validation studies. J Pers Assess 2008;90(2):185-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890701845427

33. Raine A, Benishay D. The SPQ-B: a brief screening instrument for schizotypal personality disorder. J Pers Disord 1995;9(4):346-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/pedi.1995.9.4.346

34. Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS (7th ed.). Routledge. 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003117452

|

CONFLICT OF INTEREST Authors declared no conflict of interest, whether financial or otherwise, that could influence the integrity, objectivity, or validity of their research work. GRANT SUPPORT AND FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE Authors declared no specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors |

|

DATA SHARING STATEMENT The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request |

|

|

|

KMUJ web address: www.kmuj.kmu.edu.pk Email address: kmuj@kmu.edu.pk |

APPENDIX-01

Paranoid Personality Disorder Scale

Test Instructions

Item Scoring Format

1 = Strongly Disagree. 2 = Disagree. 3 = To some extent. 4 = Agree. 5 = Strongly Agree.

No reverse scoring for any item.

|

Subscales |

Item No. |

Total items |

|

1. Suspiciousness |

1-5 |

5 |

|

2. Perceived personal attack |

6-8 |

3 |

|

3. Perceived hidden meaning of words |

9-11 |

3 |

|

4. Exploiting behaviour |

12-14 |

3 |

|

5. Bear grudges |

15-18 |

4 |

|

6. Unsuspected suspiciousness |

19-24 |

6 |

|

7. Reluctant to confide |

25-26 |

2 |

APPENDIX-02