![]() https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2025.23316 ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2025.23316 ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Development and validation of an Urdu-language Schizotypal Personality Disorder Scale: a psychometric analysis

Samia

Rashid ![]() 1,

2, Zaqia Bano 2, 3

1,

2, Zaqia Bano 2, 3 ![]()

|

1: Department of Psychology, University of Gujrat, Gujrat, Pakistan 2: Department of Psychology, National University of Medical Sciences, Rawalpindi,Pakistan 3: Department of Clinical Psychology, NUR International University, Lahore, Pakistan

Email

Contact #: +92-347- 6681017

Date Submitted: February 07, 2023 Date Revised: February 20, 2024 Date Accepted: March 09, 2024 |

|

THIS ARTICLE MAY BE CITED AS: Rasheed S, Bano Z. Development and validation of an Urdu-language schizotypal personality disorder scale: a psychometric analysis. Khyber Med Univ J 2025;17(Suppl 1):S20-S27. https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2025.23316 |

ABSTRACT

Objective: To construct a valid measure of Schizotypal Personality Disorder Scale (STPDS) in Urdu language.

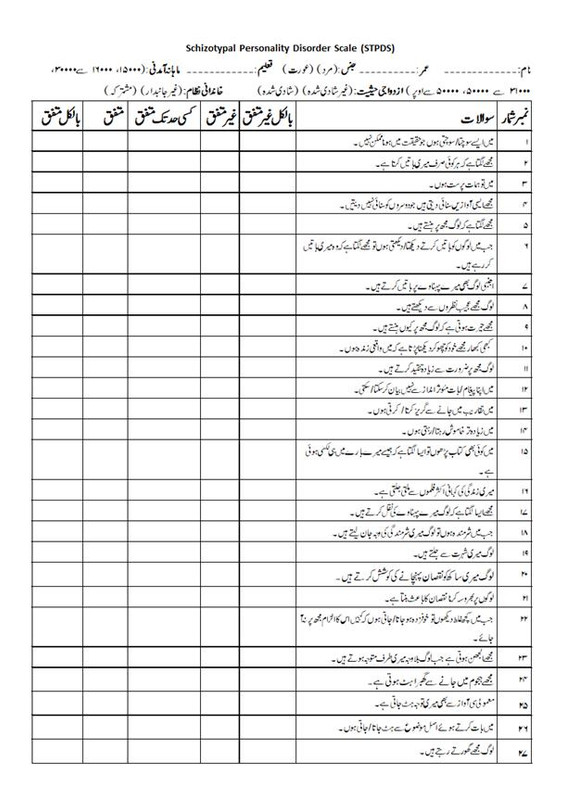

Methods: The cross-sectional analytic study, approved by Departmental Research Review Committee, University of Gujrat, was conducted from February to June 2019. In the initial phase, a 27-item STPDS was developed using standardized procedures, including exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, from an initial pool of 80 items. Data were collected from 234 participants (males=123, females=111), aged ≥18 years, recruited through purposive sampling from clinical and non-clinical populations across educational institutes, hospitals, and communities in Gujrat, Pakistan. Participants provided informed consent and completed demographic forms and questionnaires. Ethical considerations, including voluntary participation, anonymity, and confidentiality, were maintained throughout the study.

Results: The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was .929, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p<.001), confirming sampling adequacy. Exploratory factor analysis identified 7 factors explaining 66.11% of the variance, with factor loadings ranging from .40 to .78. Confirmatory factor analysis yielded a good model fit (CMIN/DF=1.876; GFI=.855; CFI=.908; RMSEA=.061). A 27-item scale was finalized, demonstrating strong psychometric properties. Cronbach’s alpha for the STPDS was .941, indicating excellent reliability, while subscales ranged from .688 to .892. Convergent validity analysis with the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire-Brief (SPQ-B) showed a moderate positive correlation (r=.454, p<.01).

Conclusion: The 27-item STPDS exhibited strong psychometric properties, including reliability and construct validity, and serves as a robust tool for assessing schizotypal personality disorder. The scale is suitable for use in clinical and non-clinical settings and may aid future research and diagnosis in this domain.

Keywords: Schizotypal personality disorder (MeSH); Eccentric behaviors (Non-MeSH); Scale development (Non-MeSH); Convergent validity (Non-MeSH); Reliability (Non-MeSH).

INTRODUCTION

Having solid and long-lasting relationships with other people is one of the main keys to happiness or contentment. Establishing personal connections and friendships with individuals can assist in overcoming negative self-perceptions and emotional distancing from others. Schizotypal personality disorder is characterized by strange ideas and imaginative thinking, severe social anxiety, thoughts that are referential, and infrequent involvement in perception. For diagnostic purposes, at least five of the nine symptoms need to be present. This condition is typically linked to stress, anxiety, and depression. Psychotic episodes that are caused by stress can range in duration from a few minutes to many hours. Between 30 and 50 percent of individuals with schizotypal personality disorder also have a severe depressive disorder diagnosis. According to the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, its prevalence in the clinical and non-clinical populations was estimated to be 3.9% in the general population and 0 to 1.9% in the clinical population, with men being more likely to experience it.1

Three phenotypic classifications with different etio-pathogenic pathways are associated with the categorical diagnosis. The first class, which is phenotypic, showed very high levels of strange look and behavior, restricted affect and aloofness, and lack of close friends. Second class: a picture of markedly elevated fairylike thoughts and abnormalities of perception. A third class, with modest levels of strange behavior, strange speech, and restrained emotion, but fairly high stages of notions of reference, social anxiety, and underhandedness. Genetic factors influence class one, familial and environmental factors influence class two, and environmental factors mostly determine class three.2 Clinically significant, schizotypal personality disorder is typically underresearched, misdiagnosed, or underrecognized, and it is associated with significant functional impairment.3

Neurodevelopmental schizotypy and pseudoschizotypy were the two categories of schizotypy identified by one study. While pseudo-schizotypy is a psychosocial entity with more fluctuating symptoms that is different from schizophrenia, neurodevelopmental type is some sort of fixed features and neurocognitive abnormalities that lean toward schizophrenia.4 Furthermore, there is a substantial correlation between this condition and other personality disorders, such as antisocial, borderline, avoidant, and paranoid personality disorders.5

A thorough investigation into the identification and management of schizotypal personality disorder was carried out. The data was extracted, and the quality was evaluated by two impartial reviewers. 54 studies in all were qualified for inclusion: 18 on diagnostic tools, 22 on pharmaceutical treatment, 3 on psychotherapy, and 13 on the disease's progression over time. We found a number of appropriate and trustworthy questionnaires for the diagnosis of schizotypal personality disorder (SIDP, SIDP-R, and SCID-II) and for screening (PDQ-4+ and SPQ). The most often researched pharmacological class was second-generation antipsychotics, which mostly included risperidone and were said to be helpful. Research on the extended course reported a moderate percentage of remission along with potential rates of conversion to other illnesses within the spectrum of schizophrenia. Making evidence-based therapy recommendations was still not feasible due to the small sample sizes and variability of the research. This was a methodical review of papers on treatment for schizotypal personality disorder and diagnostic tools. Conclusion was made that there was currently little data to support therapy choices for this condition. The information required to make evidence-based recommendations will only come from larger interventional trials.6

Even yet, there are various culture-specific and linguistic versions of the Shizotypal Personality Disorder scale available. However, in Pakistan there is no appropriate instrument that may be used to trace a proper diagnostic tool for schizotypal personality disorder to overcome cross cultural barriers. Due to the lake of indigenous personality measures in Urdu language, the current research will play a crucial role for the assessment of shizotypal personality disorder. The objective of the current study was the development of scale for adults in Urdu language and validation of shizotypal personality disorder.

METHODS

The study was approved by Departmental Research Review Committee (DRRC) of Department of Psychology, University of Gujrat, Pakistan for ethical concerns and was conducted from 15 February 2019 to th 20 June 2019. The study used cross-sectional analytical study design and the data was collected from different government and private colleges, universities, hospitals and communities of Gujrat, Pakistan.

The initial stage of research was founded on the creation of a scale for schizotypal personality disorder. The adult schizotypal personality disorder scale (STPDS) was developed using standardized scale development procedures.7 A pool of items was created to evaluate that specific condition. The ordinal level measurement was used to generate the items, which were sorted in a sequential order from weaker to stronger terms. Items were developed based on schizotypal personality disorder symptoms, literature, and diagnostic standards. The questionnaire was designed in multiple choice format. Eighty items in all were created. These objects represented the unique ideas, actions, and social interactions of each person. Following a thorough examination, 72 items related to schizotypal personality disorder were selected for testing. 55 items with a correlation of above remained after this examination.4, 16 items that had poor correlation were removed. A sample of 234 persons, 184 non-clinical and 50 clinical (male = 123, female = 111) above the age of 18, was included in the final phase. With their consent, they were selected from a wide range of educational settings, including hospitals, community centers, colleges, universities, and professional staff and students. Following confirmatory and exploratory component analysis, a 27-item scale with strong psychometric qualities was finalized.

After receiving approval from the head of the relevant institution, the participant signed an informed consent form. The participants then completed the demographic form and questionnaire.

Inclusion criteria

I. Age range of participants were between 18 years to onward.

II. Participants were recruited from both clinical and non-clinical population.

III. Participants were drafted from community, educational institutes; government and private school teachers, college and university faculty and students, and health institutes; hospitals.

IV. Both males and females were included.

V. Cultural context was considered.

Exclusion criteria

I. Below 18 years population were excluded.

II. People with Physical disability were excluded.

III. People with psychotic disorder and intellectual disability were also excluded.

Sampling technique: Purposive sampling technique was employed to recruit the participants. Purposive sampling technique is a type of non-probability sampling technique which is based on characteristics of a population and the objective of the study.

Research instruments: The instruments which were used in this study are informed consent form, demographic form and indigenous STPDS.

Ethical consideration: Ethical consideration like voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality were maintained throughout the process of research.

RESULTS

Ethical consideration: Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity’s results shown in the table. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin was .92, above the normally recommended value of i.e., .6, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p<.001) [Table I].

Table I: Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (n=234)

|

Variable |

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

Bartlett’s Test |

||

|

Chi-Square |

Df |

Sig |

||

|

Schizotypal Personality Disorder Scale (SPDS) |

.929 |

9245.256 |

1540 |

.000 |

Exploratory factor analysis initially explored 10 factors which describe 66.11% variance. Items with factor loading below .4 were eliminated, and factor loading ranging from .40 to .78. Furthermore, problematic and single item factor were rejected and revealed 7 final factors (Table II).

Table II: Factor loading of 55 item on Schizotypal Personality Disorder Scale

after varimax rotation (n=234)

|

Sr. No. |

Item No. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

1 |

38 |

.515 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

47 |

.476 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

48 |

.518 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

49 |

.631 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

50 |

.549 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

51 |

.658 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

53 |

.677 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

54 |

.731 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

55 |

.582 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

2 |

|

.542 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

6 |

|

.406 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

8 |

|

.619 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13 |

9 |

|

.781 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

10 |

|

.492 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15 |

11 |

|

.623 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16 |

12 |

|

.616 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17 |

14 |

|

.628 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18 |

26 |

|

.417 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

19 |

34 |

|

.441 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

35 |

|

.453 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

21 |

41 |

|

.438 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

22 |

1 |

|

|

.536 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

23 |

24 |

|

|

.482 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

24 |

29 |

|

|

.574 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

25 |

39 |

|

|

.447 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

26 |

40 |

|

|

.493 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

27 |

43 |

|

|

.495 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

28 |

44 |

|

|

.741 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

29 |

45 |

|

|

.542 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

30 |

13 |

|

|

|

.664 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

31 |

15 |

|

|

|

.693 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

32 |

16 |

|

|

|

.531 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

33 |

17 |

|

|

|

.592 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

34 |

18 |

|

|

|

.730 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

35 |

19 |

|

|

|

.574 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

36 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

.678 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

37 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

.458 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

38 |

31 |

|

|

|

|

.513 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

39 |

33 |

|

|

|

|

.684 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

40 |

37 |

|

|

|

|

.496 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

41 |

46 |

|

|

|

|

.443 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

42 |

23 |

|

|

|

|

|

.625 |

|

|

|

|

|

43 |

25 |

|

|

|

|

|

.651 |

|

|

|

|

|

44 |

42 |

|

|

|

|

|

.578 |

|

|

|

|

|

45 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.716 |

|

|

|

|

46 |

36 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.587 |

|

|

|

|

47 |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.457 |

|

|

|

48 |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.553 |

|

|

|

49 |

21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.575 |

|

|

|

50 |

27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.520 |

|

|

|

51 |

56 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.446 |

|

|

|

52 |

28 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.460 |

|

|

53 |

30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.659 |

|

|

54 |

32 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.564 |

|

|

55 |

52 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.548 |

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis; Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization;

Table III: Model fit summary of confirmatory factor analysis (n = 234)

|

P Value |

CMIN/DF |

GFI |

AGFI |

CFI |

RMSEA |

RMR |

|

.000 |

1.876 |

.855 |

.819 |

.908 |

.061 |

.064 |

CMIN/DF: chi-square minimum/degree of freedom; GFI: Goodness of Fit Index; CFI: Comparative Fit Index, AGFI: Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index; RMSEA: Root Mean Square of Error Approximation, RMR:root mean square residual

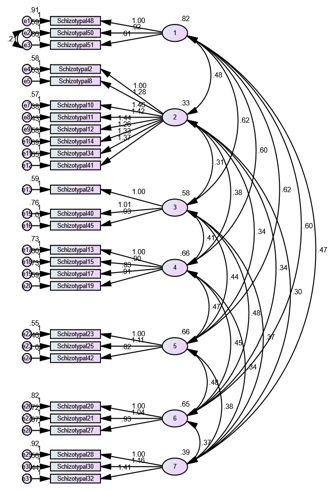

Seven factors are shown in the table as the results of the confirmatory factor analysis for adults with schizotypal personality disorder. Eliminating problematic questions like 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 16, 18, 22, 26, 29, 31, 33, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 43, 44, 46, 47, 49, 52, 53, 54, 55, and 56 was clearly beneficial.

Figure 1: Confirmatory factor analysis of Schizotypal Personality Disorder Scale

Confirmatory factor analysis resulted in 27 item Schizotypal Personality Disorder Scale for Adults (Figure 1).

Phase II: Determination of Psychometric Properties of Schizotypal Personality Disorder Scale

a) Cronbach’s alpha reliability

Table IV: Cronbach alpha of schizotypal personality disorder scale (n=234)

|

Scale |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

Number of Items |

Sig |

|

Schizotypal Personality Disorder Scale (SPDS) |

.941 |

27 |

.000 |

|

Table V: Cronbach alpha of subscales of schizotypal personality disorder scale (n=234)

|

|||

|

Total items |

Cronbach Alpha |

|

|

1. Odd beliefs |

3 |

.723 |

|

2. Unusual perceptual experiences |

8 |

.892 |

|

3. Constricted affects |

3 |

.688 |

|

4. Ideas of reference |

4 |

.763 |

|

5. Paranoid ideations |

3 |

.724 |

|

6. Social anxiety |

3 |

.692 |

|

7. Odd behavior and thinking |

3 |

.720 |

Note: **P<.01

b) Cconstruct validity of schizotypal personality disorders scale: To evaluate the convergent validity of Schizotypal Personality Disorder Scale, Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire-Brief (SPQ-B)8 used. SPQ-B is a measure to investigate the cognitive and interactive perceptual deficits.

i) Sample: Sample of 56 (N=56) Male=28, Female=28 drafted from colleges and university staff and students as well as general population.

ii) Results

Table VI: Validity analysis of schizotypal personality disorder scale (n =56)

|

Scales |

1 |

2 |

|

1 Schizotypal |

- |

|

|

2 SPQ-B |

.454** |

- |

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated strong psychometric properties for the Schizotypal Personality Disorder Scale (SPDS). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure (.929) and Bartlett’s test (p < .001) confirmed the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Exploratory factor analysis revealed seven factors explaining 66.11% of the variance, which were supported by confirmatory factor analysis (CFI = .908, GFI = .855). The scale showed excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .941) and reliable subscales (α = .688–.892). Construct validity was also confirmed through a significant correlation with the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire-Brief (r=.454, p<.01), underscoring the SPDS as a reliable and valid tool for assessing schizotypal traits.

Schizotypal personality disorder considered as creative acting and thinking and usually odd or eccentric9 and idiosyncratic.10 In addition, this disorder is strongly associated with other personality disorder comprising paranoid, borderline, avoidant, and antisocial personality disorder.11 Studies has been provided evidence of both genetic and environmental triggers for schizotypal personality.12

The precise form of the SPQ (74 items) test, known as the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire-Brief (SPQ-B), was developed based on the DSM-III-R criteria. Although it was created in a foreign language, the Five-Factor Measure of Schizotypal Personality Traits (FFM STPT) 14 is accessible. Thus, a local SPD scale was established to fill the need. The schizotypal personality factor analysis examines 10 components with a variance of 66.11%, factor loading between.40 and.78, and an acceptable Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin of.92. There was only one item with a value of less than.4. Out of the 55 items, confirmatory factor analysis identified seven factors, and 27 of them were finalized. One symptom item, "lack of close friend and associate," was poorly answered because of denial, and two other symptoms-abnormal thinking and unusual belief-were combined despite the DSM-V1 listing nine symptom criteria, which this scale only showed. There was a covariance between items 50 and 51. Every confirmatory factor analysis value-CFI=908, GFI=.855, oot Mean Square of Error Approximation (RMSEA) <0.8, and CMIN/DF <2-supported the model. The test's validity and reliability are good; its α value is.941, and its validity with the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire Brief was an acceptable.454**.

To make the study more psychometrically sound, more validation studies can be carried out to address some of its weaknesses. Participants were drawn from both the clinical and non-clinical populations; however, the clinical population's sample size was smaller than the non-clinical population's, which could have limited the participants' options. It can also be modified and translated into other languages, making it globally usable. To enhance its application in psychiatric settings, more data on clinical samples can be gathered. It is advised to determine the frequency with which schizotypal personality disorder affects both men and women in our nation.

CONCLUSION

The 27-item Indigenous STPDS, developed in Pakistani Urdu, the country's native language, is a valid and effective tool for assessing schizotypal personality. It demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including excellent reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .941) and construct validity, confirmed by its significant correlation with SPQ-B (r = .454, p < .01). The scale’s seven-factor structure, supported by both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, makes it a robust instrument for diagnosing schizotypal traits. Suitable for use in both clinical and non-clinical settings, the STPDS can aid mental health professionals, including psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers, in research and diagnostic applications, contributing to future studies in this field.

REFERENCES

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, V.A: American Psychiatric Publications 2013;669-71.

2. Battaglia M, Fossati A, Torgersen S, Bertella S, Bajo S, Maffei C, et al. A psychometric-genetic study of schizotypal disorder. Schizophr Res 1999;37(1):53-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00131-5

3. Rosell DR, Futterman SE, McMaster A, Siever LJ. Schizotypal personality disorder: a current review. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2014;16(7):452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-014-0452-1

4. Raine A. Schizotypal personality: neurodevelopmental and psychosocial trajectories. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2006;2:291-326.

5. McGlashan DA, Grilo CM, Shea MT, Yen S, Gunderson JG, Morey LC et al. Ethnicity and four personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry 2003;44(6):483-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-440x(03)00104-4

6. Kirchner SK, Roeh A, Nolden J, Hasan A. Diagnosis and treatment of schizotypal personality disorder: evidence from a systematic review. NPJ Schizophr 2018;4(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-018-0062-8

7. Tay L, Jebb A. Scale Development. In: Rogelberg SG (editor), The SAGE Encyclopaedia of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 2nd ed. 2017. SAGE Publications, New Delhi, India. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483386874

8. Raine A.The SPQ: A scale for the assessment of schizotypal personality based on DSM-III-R criteria. Schizophr Bull 1991;17(4);555-64. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/17.4.555

9. Hogan R, Hogan J. Hogan development survey manual, second edition, 1997. Tulsa; OK; Hogan Assessment Systems. [Accessed on Feb 02, 2023]. Available from URL: https://www.crownedgrace.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Hogan-Development-Survey.pdf

10. Peskin M, Raine A, Gao Y, Venables PH, Mednick SA. A developmental increase in allostatic load from ages 3 to 11 years is associated with increased schizotypal personality at age 23 years. Dev Psychopathol 2011;23(4):1059-68. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579411000496

11. McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Morey LC, et al. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: baseline axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000;102:256-64. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004256.x

12. Kendler KS, Myers J, Torgersen S, Neale MC, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. The heritability of cluster A personality disorders assessed by both personal interview and questionnaire. Psychol Med 2007;37(5):655-65. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291706009755

13. Raine A, Benishay D. The SPQ-B: a brief screening instrument for schizotypal personality disorder. J Pers Disord 1995;9(4):346-55.

14. Edmundson M, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Gore WL, Widiger TA. A five-factor measure of schizotypal personality traits. Assessment 2011;18(3):321-34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191111408228

|

Following authors have made substantial contributions to the manuscript as under:

SR & ZB: Conception and study design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, critical review,approval of the final version to be published

Authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. |

|

CONFLICT OF INTEREST Authors declared no conflict of interest, whether financial or otherwise, that could influence the integrity, objectivity, or validity of their research work.

GRANT SUPPORT AND FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE Authors declared no specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors |

|

DATA SHARING STATEMENT The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request |

|

|

|

KMUJ web address: www.kmuj.kmu.edu.pk Email address: kmuj@kmu.edu.pk |

APPENDIX-01

Schizotypal Personality Disorder Scale

Test Instructions

Item Scoring Format

1 = Strongly Disagree. 2 = Disagree. 3 = To some extent. 4 = Agree. 5 = Strongly Agree

*No reverse scoring for any item.

|

Subscales |

Item No. |

Total items |

|

1. Odd beliefs |

1-3 |

3 |

|

2. Unusual perceptual experiences |

4-11 |

8 |

|

3. Constricted affects |

12-14 |

3 |

|

4. Ideas of reference |

15-18 |

4 |

|

5. Paranoid ideations |

19-21 |

3 |

|

6. Social anxiety |

22-24 |

3 |

|

7. Odd behaviour and thinking |

25-27 |

3 |

APPENDIX-02