https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2023.23075 ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2023.23075 ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Influence

of diet patterns on time of emergence of permanent teeth of children of Quetta,

Pakistan

Nazeer Khan 1  , Mujeeb ur Rehman Baloch 2, Hasham Khan 3,

Arham Chohan 4, Sarfraz Ali Abbasi 5

, Mujeeb ur Rehman Baloch 2, Hasham Khan 3,

Arham Chohan 4, Sarfraz Ali Abbasi 5

|

1:

Professor of Biostatistics and Director ORIC, Shifa Tameer-e-Millat University,

Islamabad, Pakistan

2:

Department of Preventive/Community Dentistry, Bolan Medical College, Quetta, Pakistan

3:

Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Khyber College of Dentistry, Peshawar, Pakistan

4:

Department of Pediatric Dentistry, CMH Lahore Medical College, Lahore, Pakistan

5: Senior

Dental Surgeon, Chandka Medical College Hospital, Larkana, Pakistan

Email  :

nazeerkhan54@gmail.com :

nazeerkhan54@gmail.com

Contact #: +92-334-3471666

Date

Submitted: September 05, 2022

Date

Revised: May 08, 2023

Date

Accepted: May 16, 2023

|

|

THIS ARTICLE MAY BE CITED AS: Khan N, Baloch MuR, Khan H, Chohan A, Abbasi

SA. Influence of diet patterns on time of emergence

of permanent teeth of children of Quetta, Pakistan. Khyber Med Univ J 2023;15(2):84-90.

https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2023.23075

|

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: To

determine the effect of meat, vegetable, rice, and milk on the emergence of permanent

teeth in children from Quetta city of Baluchistan province of Pakistan.

METHODS: This

clinical cross-sectional study is part of a nationwide project, funded by

Higher Education Commission (HEC) Pakistan, was conducted in Larkana, Peshawar,

Lahore, and Quetta cities of Pakistan. The project was completed and submitted

to HEC in March 2019. Twenty-five schools (14 public; 11 private sectors) of Quetta

were selected from the list of schools using systematic random sampling. Children

were selected from the classes with at least one 'just erupted tooth’. Status of

the eruption of each tooth, height, weight, demographic information, and consumption

of food items: meat, rice, vegetable, and milk in their family were recorded for

each selected student.

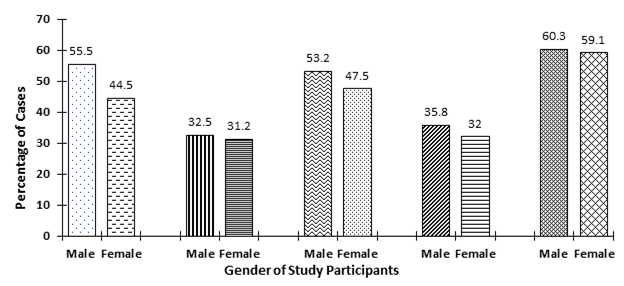

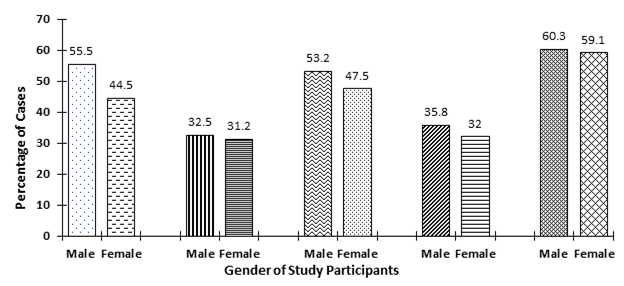

RESULTS: Out

of 1267 children fulfilling the criterion of 'just erupted' tooth’, 703 (55.5%)

were males. Mean of age, weight, height, and body mass index were 9.5±2.3

years, 27.9±10.4 kg, 131.7±14.3 cm, and 15.5±3.5 kg/m2,

respectively. The minimum and maximum values of the 1st quartile, median,

and 3rd quartiles of time of eruption belonged to tooth numbers #16 and

#17, respectively. Twenty out of 28 teeth showed early eruption in females than

males, however, only four were statistically significant (p<0.05). Frequent users

(≥4 days/week) of meat, rice, and milk showed early eruption of 68%, 61%, and 71%

of the teeth respectively.

CONCLUSION: Children

from Quetta showed early eruption of permanent teeth among frequent users of rice,

meat, and milk products.

KEYWORDS: Children

(MeSH); Baluchi children (Non-MeSH); Balochistan (Non-MeSH); Diet (MeSH); Eruption time (Non-MeSH); Pakistan (MeSH); Tooth

(MeSH); Permanent tooth (Non-MeSH); Dentition (MeSH); Dentition, Permanent (MeSH).

INTRODUCTION

The

mechanical movement of a permanent tooth from the alveolar bone to the oral cavity

is defined as the emergence of the permanent tooth.1 This information

which is the sequence and the time of emergence of permanent teeth is quite useful

in pediatric dentistry, orthodontics, oral surgery, and forensic dentistry.2

It is indicated in the literature that this information should be collected from

the population, in which they are going to be used.3 Therefore many countries,

covering all the five inhabited continents, have conducted studies on the time and

sequence of emergence of permanent teeth for their population as indicated by Khan,2-4

however, only a few studies have been conducted for Pakistan.1,2,4-8

It should be noted that one study was conducted before the partition of the subcontinent.8

Literature reports that the time and sequence of emergence of permanent teeth may

be influenced by many factors, such as gender, dietary patterns, low birth weight,

premature delivery, socioeconomic status, malnutrition, obesity, and endocrinology

condition.9 But most of the studies have confined themselves to discussing

only the effect of gender on the emergence of permanent teeth. However, the dietary

patterns/nutrition status, which is also an important factor, has been discussed

only by a limited number of studies.1,5,8-12 In Pakistan, only a few

studies1,5,8 have been conducted on this subject. They have been conducted

on the children of Larkana (Sindh), Peshawar (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa),5 and

Lahore (Punjab).8 But until now, none of the studies have discussed the

effect of dietary patterns on the emergence of teeth in Baluchi children. Since

different population consumes different food; culturally or customarily. Therefore,

the dietary patterns of Baluchi foods may have a different effect on the emergence

of teeth, as compared to the dietary patterns of other provinces of Pakistan. Hence

the objective of the study was to determine the effect of meat, vegetable, rice,

and milk on the emergence of permanent teeth in Quetta children.

The

outcomes of this study will be helpful to the children and the parents by increasing

their knowledge of mean and range of eruption of individual teeth of Baluchi children.

This information will also give some understanding to the pediatric dental specialists

to collect the information regarding the dietary habits of the children, along with

the other inducing factors to determine the early or late eruption of permanent

teeth, which would help the dentists in pediatric treatment plans and orthodontic

interventions.

METHODS

This

cross-sectional study was a part of nationwide project conducted in Larkana, Peshawar,

Lahore, and Quetta; cities of Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab &

Baluchistan provinces of Pakistan respectively. The study was funded by the Higher

Education Commission (HEC) of Pakistan and project was completed and submitted to

HEC in March 2019. The sample size was computed using the outcome of a large-scale

study conducted by the principal investigator on Karachi children,4 using

the following sample size calculator, https://www.gigacalculator.com/calculators/power-sample-size-calculator.php

The information inserted for the computation

was a 95% confidence interval, 98% of the power of the test, a margin of error of

0.2 years of the mean of 11.3 years, and a standard deviation of 1.7 years of left

maxillary 2nd molar of the study.4 The total sample size was

7500 school children. It was divided into the sample sizes of four study centers.

The portion of Quetta sample was 1300 school children, equally divided into male

and female children. Twenty-five schools (14 public and 11 private sectors) were

selected from the list of schools of the city of Quetta, using systematic random

sampling. Children were selected from the classes, based on parents' written consent

and children's assent with at least one 'just erupted tooth’. Just erupted tooth

was defined as a tooth deemed to have emerged if any part of it is visible in the

mouth. Inclusion criteria were the consent of parents with the assent of the child

and Pakistani nationality. The exclusion criteria were systemic diseases, syndromes,

and local alterations of dental eruption, such as dentigerous cysts, craniofacial

deformities, general developmental disorders, and dental anomalies (including dental

agenesis). Height and weight were measured in centimeters and kilograms, respectively,

using a height-weight machine without shoes in the sunlight, and a questionnaire

was administrated. Along with demographic information, the amount of meat, rice,

vegetable, and milk, usually consumed in their family were recorded. The study was

approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Dow University of Health Sciences

(No. IRB-B-17/DUHS-10). The detailed methodology of the study is discussed in Khan

et al,.2,4 The qualitative variables were age, height, weight, time of

eruption of all 28 teeth, and quantity of food items (meat, vegetable, rice, and

milk) used most of the time in their homes. The qualitative variables were class,

gender, place of birth, and race of the child. Data was entered and analyzed using

SPSS (version 23.0). Descriptive statistics such as mean, median, standard deviation,

and interquartile range were computed for quantitative variables, while frequency

and percentages were reported for qualitative variables. The interquartile range

is the difference between the 1st and the 3rd quartiles of

the data, while the median is the 2nd quartile. The normality assumption

of the quantitative variables was assessed using a one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov

test. Two-sample 't- test was employed if the normality assumption was fulfilled,

otherwise, the Mann-Whitney test was applied for comparison of the mean eruption

time of two groups of food items as mentioned above for less (≤3 times a week)

and more frequent (≥4 times a week) consumption. The mean eruption time was also

compared for male and female children. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically

significant.

RESULTS

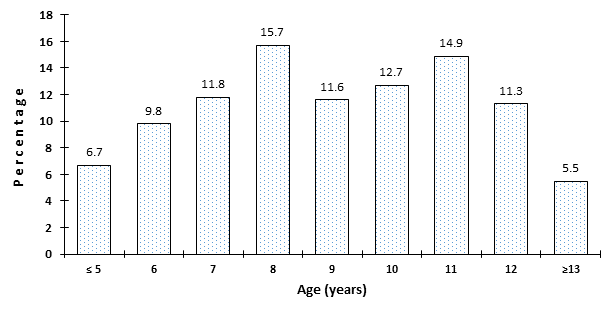

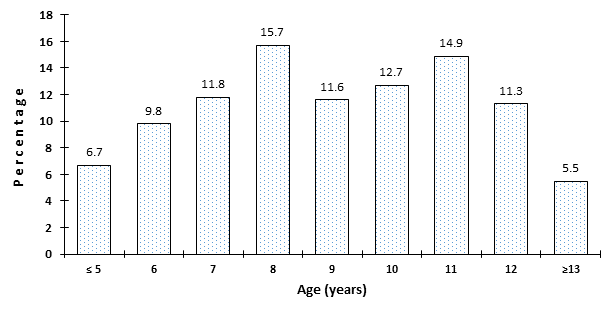

One

thousand two hundred sixty-seven (1267) children fulfilled the criterion of 'just

erupted tooth' from 25 selected schools. Out of 1267 children, 703 (55.5%) were

males and 564 (44.5%) were females (Figure 1), and the largest group (n =198; 15.7%)

of the children belonged to 8 years.

Figure 1:

Percentage of number of cases, frequent user (≥ 4 days/week) of meat,

vegetable, rice and milk of males and females.

(Figure

2). The mean of age, weight, height, and Body Mass Index (BMI) were 9.5±2.3

years, 27.9±10.4 kg, 131.7±14.3 cm, and 15.5±3.5 kg/m2,

respectively.

Figure 2

: Percentage of the age of the children

Table

I shows the 3rd, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th,

90th, and 97th percentile values of the time of eruption of

all the teeth, except the third molars. The minimum value of the 3rd

percentile belonged to the right mandibular 1st molar (#46) with a value

of 4.6 years, while the maximum value of the 3rd percentile was for the

mandibular left 2nd molar (#37) with a value of 8.9 years. The minimum

of 10th percentiles corresponded to the right mandibular 1st

molar (#46) with a value of 4.6 years, while the maximum value for this percentile

belonged to the maxillary 2nd molar (#17) with a value of 11.1 years.

The minimum value of 1st quartile (25th percentile) belonged

to maxillary right 1st molar (#16) with a value of 5.2 years, while the

maximum value also belonged to the same quadrant, mandibular right 2nd

molar (#17) with a value of 11.8 years. The median values (50th percentile)

of the time of eruption showed that the minimum value belonged to 1st

molars of right mandibular and maxillary teeth (#16 & #46) with the value of

5.5 years, while the maximum value corresponding to the right maxillary tooth (#17)

with the value of 12.5 years. The minimum value in the list of the 3rd

quartile (75th percentile) was 5.7 years corresponding to the maxillary right 1st

molar (#16), while the maximum value of 13.3 years also belonged to

the

2

nd molar (#17) of the same quadrant. Since the values of the 90

th

and 97

th percentiles were quite close to each other. Therefore, the 97

th

percentile is discussed here. The minimum value of this percentile belonged to the

1

st mandibular right molar (#16) with a value of 6.3 years, while the

maximum value was 15.1 years corresponding to the left mandibular 2

nd

molar (#27).

Table I: Percentiles (3rd, 10th, 25th, 50th,

75th, 90th, and 97th) eruption time of all the teeth, except third molars

|

Tooth No.

|

P3

|

P10

|

P25

|

P50

Median

|

P75

|

P90

|

P97

|

Tooth No.

|

P3

|

P10

|

P25

|

P5

Median

|

P75

|

P90

|

P97

|

|

17

|

8.3

|

11.1

|

11.8

|

12.5

|

13.3

|

14.1

|

14.6

|

47

|

8.7

|

10.8

|

11.5

|

12.0

|

12.4

|

13

|

13.3

|

|

16

|

4.8

|

5.0

|

5.2

|

5.5

|

5.7

|

6.2

|

6.3

|

46

|

4.6

|

4.6

|

5.3

|

5.5

|

5.8

|

7.4

|

7.4

|

|

15

|

6.5

|

9.6

|

10.5

|

11.3

|

12.4

|

13.4

|

14.4

|

45

|

9.9

|

11.1

|

12.4

|

11.8

|

12.9

|

13.4

|

9.9

|

|

14

|

7.8

|

8.7

|

9.0

|

9.8

|

10.8

|

11.6

|

12.8

|

44

|

8.6

|

9.0

|

9.6

|

10.3

|

11

|

11.6

|

12.3

|

|

13

|

7.8

|

9.0

|

10.4

|

11.4

|

12.3

|

13.2

|

13.7

|

43

|

7.9

|

8.1

|

8.7

|

9.2

|

10.3

|

11.3

|

12.5

|

|

12

|

6.1

|

6.8

|

7.7

|

8.3

|

8.8

|

10.6

|

12.2

|

42

|

6.3

|

6.7

|

7.0

|

7.4

|

8.1

|

8.5

|

8.5

|

|

11

|

5.9

|

6.2

|

6.5

|

7.0

|

7.5

|

8.2

|

8.5

|

41

|

5.2

|

5.6

|

5.8

|

6.3

|

6.9

|

7.3

|

7.9

|

|

21

|

5.7

|

5.9

|

6.3

|

6.7

|

7.3

|

8

|

8.7

|

31

|

5.2

|

5.6

|

5.9

|

6.3

|

6.9

|

7.5

|

8.8

|

|

22

|

6.6

|

7.3

|

7.7

|

8.1

|

8.6

|

10

|

12.6

|

32

|

5.8

|

6.7

|

7.1

|

7.4

|

8

|

8.9

|

8.5

|

|

23

|

8.7

|

9.0

|

10.0

|

11.1

|

12.1

|

13.3

|

13.5

|

33

|

7.8

|

8.0

|

8.5

|

9.3

|

10.4

|

11.4

|

12.2

|

|

24

|

8.2

|

8.6

|

9.1

|

10.0

|

11.1

|

11.9

|

12.6

|

34

|

7.7

|

8.4

|

9.0

|

9.9

|

11.2

|

11.9

|

13.7

|

|

25

|

9.3

|

10

|

10.5

|

11.1

|

11.9

|

13.1

|

13.7

|

35

|

10.3

|

10.6

|

11

|

11.5

|

12.4

|

13.4

|

13.4

|

|

26

|

4.7

|

4.9

|

5.3

|

5.6

|

6.0

|

7.2

|

7.2

|

36

|

5.2

|

5.2

|

5.5

|

5.8

|

6.4

|

8.0

|

8.0

|

|

27

|

8.8

|

10.5

|

11.5

|

12.4

|

13.0

|

13.5

|

15.1

|

37

|

8.9

|

10.6

|

11.6

|

12.2

|

12.9

|

13.6

|

14.1

|

The

median, interquartile range, and the comparison of the time of eruption for the

male and female children are shown in Table II. Twenty out of 28 teeth (more than

70%) showed that the female children erupted earlier than male children. Four teeth

(#47, #43, #42, and #33) showed significant differences with p-values of 0.05, 0.003,

0.046, and 0.003, respectively. However, two of them showed early eruption for males,

and 2 teeth showed another way around. But all of them belonged to mandibular teeth.

The remaining tables discuss the consumption of meat, vegetable, rice, and milk,

divided into less frequent consumption (≤ 3 days/week) and more frequent consumption

(≥ 4 days/week).

Table II: Comparison of median values of time of

eruption of males and females children

|

Tooth

No.

|

Male

|

Female

|

p-value

|

Tooth

No.

|

Male

|

Female

|

p-value

|

|

Median

(Inter quartile range)

|

Median

(Inter quartile range)

|

Median

(Inter quartile range

|

Median

(Inter quartile range)

|

|

17

|

12.6

(11.8, 13.4)

|

12.5

(11.4, 12.8)

|

0.366

|

47

|

12.3

(11.5, 12.8)

|

11.7

((11.5, 13.1)

|

0.050

|

|

16

|

5.6 (5.1,

5.7)

|

5.4 (5.2,

5.6)

|

0.536

|

46

|

5.6 (5.2,

7.4)

|

5.5 (5.3,

5.6)

|

0.633

|

|

15

|

11.3

(10.5, 12.3)

|

11.0

(10.2, 12.0)

|

0.441

|

45

|

11.8

(11.2, 12.6)

|

11.9

(10.8, 12.4)

|

0.949

|

|

14

|

9.3 (9.0,

10.9)

|

9.8 (9.2,

10.8)

|

0.310

|

44

|

10.3

(9.6, 11.2)

|

10.4

(9.6, 10.9)

|

0.788

|

|

13

|

11.6

(10.8, 12.3)

|

11.0

(10.1, 12.1)

|

0.075

|

43

|

8.8 (8.5,

9.9)

|

9.8 (8.9,

10.8)

|

0.003

|

|

12

|

8.3 (7.5,

9.3)

|

8.3 (7.7,

8.8)

|

0.889

|

42

|

7.6(7.3,

8.3)

|

7.2 (6.8,

8.1)

|

0.046

|

|

11

|

7.1 (6.6,

7.5)

|

6.8 (6.3,

7.7)

|

0.336

|

41

|

6.4 (5.9,

6.9)

|

6.1 (5.7,

6.8)

|

0.399

|

|

21

|

6.8 (6.3,

7.4)

|

6.5 (6.1,

7.1)

|

0.117

|

31

|

6.4 (5.9,

7.0)

|

6.3 (5.9,

6.8)

|

0.332

|

|

22

|

8.2 (7.8,

9.0)

|

8.0 (7.7,

8.4)

|

0.290

|

32

|

7.4 (7.2,

8.0)

|

7.5 (7.0,

8.1)

|

0.745

|

|

23

|

11.1

(10.1, 12.3)

|

11.0

(9.8, 11.9)

|

0.578

|

33

|

8.7 (8.1,

9.8)

|

9.8 (8.8,

11.2)

|

0.003

|

|

24

|

10.3

(9.3, 11.6)

|

9.6 (8.8,

11.1)

|

0.053

|

34

|

9.5 (9.0,

11.3)

|

10.3

(8.9, 11.0)

|

0.908

|

|

25

|

11.1

(10.7, 12.0)

|

11.0

(10.2, 12.0)

|

0.540

|

35

|

11.9

(11.1, 12.8)

|

11.2

(10.9, 11.8)

|

0.127

|

|

26

|

5.9 (5.6,

7.6)

|

5.5 (5.3,

7.8)

|

0.181

|

36

|

6.3 (5.7,

8.2)

|

5.5 (5.7,

8.2)

|

0.222

|

|

27

|

12.3

(11.5, 12.9)

|

12.5

(11.9, 13.3)

|

0.244

|

37

|

12.3

(11.6, 13.1)

|

12.0

(11.6, 13.1)

|

0.862

|

Table

III discusses the consumption of meat during a usual week. The table shows that

the children with the time of eruption of 19 out of 28 teeth indicated early eruption

for less frequent users of meat products as compared to more frequent users. Most

of the teeth of early eruption with more frequent meat product users had very few

samples (n≤ 5). Three mandibular teeth (#46, #43, and #33) showed statistically

significant p-values of 0.019, 0.003, and 0.007, respectively of early eruption

as compared to the more frequent users.

Table III: Comparison of eruption time among 2

categories of meat consumption

|

Tooth No.

|

No. of cases

|

≤ 3 times/week*

|

No. of cases

|

≥ 4 times/week*

|

P value

|

Tooth No.

|

No. of cases

|

≤ 3 times/week*

|

No. of cases

|

≥ 4 times/week*

|

P value

|

|

17

|

36

|

12.4±1.4

|

8

|

12.7±1

|

0.475

|

47

|

45

|

11.9±1.3

|

10

|

11.8±0.7

|

0.899

|

|

16

|

13

|

5.5±0.4

|

1

|

5.3±0.0

|

0.737

|

46

|

13

|

6.7±2.6

|

1

|

7.4±0.0

|

0.019

|

|

15

|

31

|

11.3±1.9

|

13

|

11.6±1.2

|

0.604

|

45

|

29

|

11.5±1.2

|

9

|

12.0±0.7

|

0.346

|

|

14

|

65

|

9.9±1.1

|

15

|

10.3±1.7

|

0.342

|

44

|

50

|

10.3±1

|

8

|

10.3±1

|

0.896

|

|

13

|

79

|

11.1±1.6

|

22

|

11.6±1.1

|

0.138

|

43

|

91

|

9.4±1.2

|

15

|

10.4±1.2

|

0.003

|

|

12

|

52

|

8.4±1.4

|

3

|

8.9±2.3

|

0.559

|

42

|

52

|

7.6±1

|

3

|

7.3±0.3

|

0.566

|

|

11

|

61

|

7.1±0.7

|

3

|

8.0±2.0

|

0.489

|

41

|

51

|

6.4±0.7

|

1

|

5.6±0.0

|

0.240

|

|

21

|

53

|

6.8±0.8

|

5

|

7.3±1.8

|

0.611

|

31

|

46

|

6.5±0.9

|

2

|

5.8±0.4

|

0.165

|

|

22

|

71

|

8.5±1.3

|

5

|

7.6±0.8

|

0.070

|

32

|

44

|

7.6±0.9

|

6

|

7.9±2.2

|

0.502

|

|

23

|

57

|

10.9±1.4

|

20

|

11.6±1.4

|

0.067

|

33

|

61

|

9.3±1.3

|

13

|

10.4±0.9

|

0.007

|

|

24

|

66

|

10.1±1.4

|

11

|

10.4±1.2

|

0.485

|

34

|

38

|

10.1±1.2

|

7

|

10.2±2.2

|

0.923

|

|

25

|

26

|

11.4±1.2

|

8

|

10.9±0.8

|

0.247

|

35

|

21

|

11.8±1.1

|

6

|

11.9±1.1

|

0.741

|

|

26

|

15

|

6.6±2.4

|

1

|

10.6± 0.0

|

0.131

|

36

|

13

|

6.9±2.1

|

1

|

5.4±0.0

|

0.511

|

|

27

|

28

|

12.3±1.1

|

9

|

12.0±1.8

|

0.656

|

37

|

48

|

12.0±1.4

|

19

|

12.3±1.3

|

0.395

|

* Mean±Standard Deviation

The

vegetable consumption related to time of eruption is shown in Table IV. Seventeen

teeth showed early eruption for less frequent consumers of vegetable dishes. However,

none of the pairs of less or more frequent consumers, except tooth #41 (p=0.028),

showed any statistical significance.

Table IV: Comparison of eruption time among 2

categories of vegetable consumption

|

Tooth No.

|

No. of cases

|

≤ 3 times/week*

|

No. of cases

|

≥ 4 times/week*

|

P value

|

Tooth No.

|

No. of cases

|

≤ 3 times/week*

|

No. of cases

|

≥ 4 times/week*

|

P value

|

|

17

|

10

|

12.5±0.8

|

15

|

12.0±1.9

|

0.425

|

47

|

16

|

11.4±1.8

|

13

|

11.8±0.7

|

0.470

|

|

16

|

2

|

5.7±0.1

|

3

|

5.8±0.4

|

0.819

|

46

|

5

|

8.0±3.5

|

2

|

12.3±0.2

|

0.166

|

|

15

|

15

|

11.9±1.3

|

13

|

11.2±1.5

|

0.146

|

45

|

15

|

12.0±1.0

|

12

|

11.3±1

|

0.107

|

|

14

|

26

|

9.9±1.1

|

23

|

10.1±1.5

|

0.523

|

44

|

21

|

10.2±1

|

17

|

10.1±0.8

|

0.860

|

|

13

|

32

|

11.5±1.3

|

33

|

11.4±1.2

|

0.793

|

43

|

26

|

9.8±1.2

|

38

|

9.4±1.3

|

0.194

|

|

12

|

17

|

8.2±1

|

19

|

8.5±2

|

0.659

|

42

|

22

|

7.6±0.6

|

16

|

7.7±1.2

|

0.921

|

|

11

|

17

|

7.2±0.6

|

14

|

7.5±1.1

|

0.306

|

41

|

15

|

6.4±0.5

|

8

|

6.9±0.5

|

0.028

|

|

21

|

15

|

6.8±0.7

|

15

|

7.2±1.2

|

0.283

|

31

|

10

|

6.6±0.5

|

8

|

6.8±0.9

|

0.507

|

|

22

|

26

|

8.5±1

|

23

|

8.4±1.5

|

0.821

|

32

|

16

|

7.6±1.4

|

14

|

8.1±0.9

|

0.256

|

|

23

|

22

|

11.2±1.6

|

27

|

10.7±1.3

|

0.316

|

33

|

23

|

9.5±1.4

|

21

|

9.6±1.4

|

0.968

|

|

24

|

21

|

10.1±1.5

|

24

|

10.3±1.2

|

0.684

|

34

|

13

|

9.7±1.4

|

16

|

9.8±1.4

|

0.877

|

|

25

|

11

|

10.9±0.5

|

8

|

11.8±1.2

|

0.088

|

35

|

11

|

11.7±1

|

9

|

11.9±0.8

|

0.640

|

|

26

|

4

|

7.3±2.5

|

4

|

7.1±2.4

|

0.927

|

36

|

5

|

6.7±1.3

|

2

|

7.9±3.2

|

0.441

|

* Mean±Standard Deviation

Table

V shows the use of a rice diet in a usual week for children with just erupted teeth.

Most of the teeth with just eruption (17 teeth out of 28) showed late eruption with

less frequent (≤ 3 days/week) consumption of rice. One tooth (#26), did not have

any case for the more frequent group, therefore was not considered. Only one tooth

(#44) showed significantly early eruption for the more frequent group of rice consumption

(p-value 0.030).

Table V: Comparison of eruption time among 2

categories of rice consumption

|

Tooth

No.

|

No. of

cases

|

≤ 3 times/week*

|

No. of

cases

|

≥ 4 times/week*

|

P value

|

Tooth

No.

|

No. of

cases

|

≤ 3

times/week*

|

No. of

cases

|

≥ 4 times/week*

|

P value

|

|

17

|

42

|

12.4±1.3

|

2

|

12.5±0.1

|

0.894

|

47

|

53

|

11.8±1.2

|

2

|

12.4±0.1

|

0.539

|

|

16

|

13

|

5.5±0.4

|

1

|

5.3±0.1

|

0.737

|

46

|

12

|

7.5±3.4

|

2

|

5.5±0.1

|

0.431

|

|

15

|

43

|

11.4±1.7

|

1

|

12.6±

|

0.483

|

45

|

36

|

11.7±1.1

|

2

|

10.8±2.3

|

0.279

|

|

14

|

76

|

9.9±1.2

|

4

|

10±1.7

|

0.973

|

44

|

58

|

10.4±0.9

|

1

|

8.3±0.0

|

0.030

|

|

13

|

89

|

11.1±1.6

|

12

|

11.9±1.1

|

0.088

|

43

|

92

|

9.5±1.2

|

14

|

9.7±1.3

|

0.661

|

|

12

|

53

|

8.4±1.4

|

2

|

8.0±1.6

|

0.649

|

42

|

50

|

7.7±1.0

|

5

|

7.3±0.4

|

0.396

|

|

11

|

60

|

7.1±0.8

|

3

|

6.5±0.3

|

0.194

|

41

|

43

|

6.5±0.7

|

10

|

6.1±0.7

|

0.074

|

|

21

|

52

|

6.9±0.9

|

5

|

6.3±0.4

|

0.133

|

31

|

41

|

6.6±0.9

|

8

|

6.1±0.8

|

0.176

|

|

22

|

70

|

8.4±1.1

|

6

|

9.0±2.4

|

0.575

|

32

|

50

|

7.7±1.2

|

2

|

7.1±0.2

|

0.452

|

|

23

|

70

|

11.1±1.5

|

7

|

10.9±1.2

|

0.744

|

33

|

66

|

9.5±1.3

|

8

|

9.6±1.2

|

0.801

|

|

24

|

75

|

10.1±1.4

|

3

|

9.1±1.3

|

0.231

|

34

|

38

|

10.1±1.4

|

7

|

10.0±1.2

|

0.945

|

|

25

|

30

|

11.2±1.1

|

4

|

11.5±1.5

|

0.605

|

35

|

25

|

11.9±1.1

|

2

|

10.8±0.2

|

0.178

|

|

26

|

16

|

6.8±2.5

|

0

|

|

|

36

|

11

|

7.2±2.2

|

3

|

5.4±0.2

|

0.204

|

|

27

|

30

|

12.0±1.3

|

7

|

13.0±1.1

|

0.063

|

37

|

60

|

12.1±1.4

|

7

|

12.0±1.5

|

0.885

|

* Mean±Standard Deviation

The

consumption of milk by the children of the sample is discussed in Table VI. Only

8 teeth out of 28 showed early eruption in the children with less frequent users.

However, 12 teeth showed significantly early eruption for the children with the

more frequent user of milk drinkers.

Table VI: Comparison of eruption time of Quetta

children among 2 categories of milk consumption

|

Tooth

No.

|

No. of

cases

|

≤ 3 cups/week*

|

No. of

cases

|

≥ 4 cups/week*

|

P value

|

Tooth

No.

|

No. of

cases

|

≤ 3 cups/wee*k

|

No. of

cases

|

≥ 4 cups/week*

|

P value

|

|

17

|

24

|

12.8±1

|

20

|

12.0±1.5

|

0.040

|

47

|

30

|

12.0±0.6

|

25

|

11.7±1.6

|

0.327

|

|

16

|

6

|

5.3±0.5

|

8

|

5.6±0.3

|

0.284

|

46

|

4

|

8.0±4.2

|

10

|

7.0±2.9

|

0.593

|

|

15

|

24

|

11.3±1.8

|

20

|

11.5±1.5

|

0.746

|

45

|

24

|

12.0±0.9

|

14

|

11.0±1.2

|

0.009

|

|

14

|

32

|

10.4±1.4

|

47

|

9.7±1.0

|

0.013

|

44

|

26

|

10.7±0.8

|

33

|

10.1±1

|

0.018

|

|

13

|

50

|

11.5±1.3

|

51

|

10.9±1.7

|

0.040

|

43

|

36

|

10.2±1.3

|

69

|

9.2±1.1

|

<0.001

|

|

12

|

14

|

9.6±1.8

|

41

|

8.0±1.0

|

0.007

|

42

|

9

|

7.9±1.4

|

45

|

7.6±0.9

|

0.344

|

|

11

|

14

|

6.8±0.7

|

49

|

7.2±0.8

|

0.105

|

41

|

19

|

6.2±0.7

|

34

|

6.6±0.7

|

0.042

|

|

21

|

12

|

6.6±0.6

|

45

|

6.9±0.9

|

0.254

|

31

|

18

|

6.3±0.8

|

31

|

6.6±0.9

|

0.195

|

|

22

|

22

|

9.0±1.5

|

54

|

8.2±1.1

|

0.017

|

32

|

6

|

7.6±0.4

|

45

|

7.7±1.2

|

0.726

|

|

23

|

37

|

11.4±1.3

|

40

|

10.8±1.5

|

0.077

|

33

|

24

|

10.0±1.2

|

49

|

9.3±1.3

|

0.044

|

|

24

|

34

|

10.6±1.3

|

44

|

9.7±1.3

|

0.005

|

34

|

18

|

10.1±1.5

|

27

|

10.0±1.4

|

0.797

|

|

25

|

14

|

11.5±1.1

|

20

|

11.1±1.1

|

0.237

|

35

|

15

|

11.8±0.9

|

12

|

11.9±1.3

|

0.753

|

|

26

|

7

|

7.6±3.3

|

9

|

6.3±1.7

|

0.324

|

36

|

5

|

8.0±2.7

|

9

|

6.2±1.5

|

0.140

|

|

27

|

19

|

12.7±1

|

18

|

11.7±1.4

|

0.013

|

37

|

30

|

12.7±1.1

|

37

|

11.9±1.5

|

0.273

|

* Mean±Standard Deviation

DISCUSSION

The

objective of the study was to determine the effect of food items such as meat, vegetable,

rice, and milk on the emergence of permanent teeth in Quetta children. Quetta is

the largest city and provincial capital of Baluchistan. Even though the total number

of inhabitants of Baluchistan is only 3.6% of the total population of Pakistan,

but area wise this is the largest province and covers about 42% of the total area

of Pakistan. The Baluchi people are Iranian natives living mainly in the Baluchistan

provinces of Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan.13 Due to their differences

in genetics13 and life style14 as compared to other populaces

of Pakistan, the dieting patterns of inhabitants of this province are also quite

different. As mentioned in Introduction section that the emergence of permanent

teeth are also affected due to the dieting patterns and food consumption.

Twenty-five

schools were randomly selected from 518 high schools in Quetta, which was about

5% of the total number of schools. Male children were more than 10% than female

children; 55:45. This ratio is a little bit different from a study by Ali et al.,15

which was tilted toward the girls' side, indicated as 60:40 in 2018. About 80% of

the cases were found among children of 7 to 12 years. The percentage of the children

in this range is in agreement with Khan's4 study of Karachi children.

It is because the admission in first grade is about 5 to 6 years in all over Pakistan.

Therefore, there is no change in age-groups from grade 1 to grade 10 in all the

schools.

Comparing

the outcomes of this study regarding the first quartile (P25), median (P50), and

third quartile (P75) of eruption time of maxillary teeth with reported data showed

that the Quetta children had an early eruption for the first permanent molar than

Indian (Hyderabad),17 Sri Lankan,18 Karachi (Pakistan),4

Peshawar (Pakistan)5 children. However, it is almost the same as the

eruption time of the maxillary first molar of Larkana (Pakistan)6 children.

Furthermore, the children of Quetta had a late eruption for the 2nd maxillary

molar as compared to Indian (Hyderabad),17 Sri Lankan,18 Pakistani

(Larkana,6 Karachi,4 and Peshawar5) children. It

implies that the eruption of teeth of Quetta children has more variation in eruption

time as compared to all other studies reported from Pakistan and other neighboring

countries. Higher variation has also been detected among the eruption of first permanent

mandibular molars and 2nd permanent molars against studies published

in Pakistan and neighboring countries.

In

most of the cases (20 out of 28 teeth) the median eruption time of females was earlier

than male children. However, only two of them were statistically significant. This

outcome is in agreement with some of the studies conducted in Central America (Costa

Rica),19 and North Africa (Egypt).20 Furthermore, most of

the studies performed in Asia (India and Pakistan)2,4,6 showed the same

trend as this study. However, most of the studies conducted in American and European

countries showed significant early eruption time of girls as compared to boys.11,16,21,22

Khan

et al., 5 indicated the main ingredients and its quantities in rice,

meat, vegetable, and milk. Major components in rice, meat, vegetable, and milk are,

carbohydrate, protein, minerals (calcium, magnesium, etc), and fate & calcium,

respectively.

The

main ingredient of rice is carbohydrates. The starchy food produces the acid up

to 20 minutes after it comes in contact with the oral cavity. This acid damages

the primary teeth by developing dental caries and extraction occurs. Consequently,

the permanent teeth erupt earlier.5 May be due to this reason, this study

showed that 17 out of 28 (61%) teeth erupted earlier for the children who consumed

the rice diet more frequently. Furthermore, milk which is full of fat and calcium

makes the teeth strong and healthy.5 Excessive use of meat and milk makes

the body obese and heavy.23 Literature indicates that there is a direct

relationship between obesity and early eruption of primary and permanent teeth.1,5,9

Therefore, more frequent use of these foods affects early eruption as shown in our

results.

There

are a few other factors that could have affected the outcomes of this study. Firstly,

this study was conducted in regular schools. So religious schools and out-of-school

children are not included. In religious schools, the children are fed with monotonous

foods with only a few variations. The children who are out of school are mostly

from low socio-economic groups. Their dieting habits are different from the socio-economic

groups of above their level. These two groups are not included and it could have

skewed the results. Secondly, the survey was based on self-reported information.

It is usually the tendency of human beings, especially children to show off a better

standard of living in their family, which is called a 'desirable bias' and consequently

could have reported higher values concerning the consumption of meat and milk.1

Furthermore the meals on the Pakistani dining tables contain mixed food items

due to the nucleus family system, and asking for different food items separately

could also strengthen the 'desirable biases'. Therefore the outcomes of this study

should be read with caution due to the above-mentioned limitations.

This

study covers only four types of food items without going into further detail. Hence

a study with a larger variety and quantity of food consumption is needed to verify

these results regarding the effect of dietary patterns on the time of eruption of

permanent teeth.

CONCLUSIONS

The

study concludes that the duration of the eruption of permanent teeth of children

from Quetta city of Baluchistan province of Pakistan, from the first tooth to the

last tooth (most of the time 2nd molars) has a large variation as compared

to the children of other provinces. Children from Quetta showed early eruption of

permanent teeth among frequent users of rice, meat, and milk products.

REFERENCES

1.

Khan N, Abbasi SA, Khan H, Baloch MR, Chohan AN. Effect of dietary

pattern on the emergence of permanent teeth of the children of Larkana, Pakistan.

Ibnosina J Med Biomed Sci 2022;14(1):28-34. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1748671

2.

Khan N, Khan H, Baloch MR, Abbasi SA. Time of Emergence of permanent

teeth of the children of Peshawar, Pakistan. J Pak Dent Assoc 2019;28(4):154-61. https://doi.org/10.25301/JPDA.284.154

3.

Khan NB, Chohan AN, Al Mograbi B, Al-Deyab S, Zahid T, Al Moutairi

M. Eruption time of permanent first molars and incisors among a sample of Saudi

male school children. Saudi Dent J 2006;18(1):18-24.

4.

Khan N. Emergence time of permanent teeth in Pakistani children. Iranian

J Public Health 2011;40(4):63-73.

5.

Khan H, Khan N, Baloch MR, Abbasi SA. Effect of diet on eruption times

for permanent teeth of children in Peshawar. Pak Oral Dent J 2020;40(1):24-30.

6.

Khan N, Abbasi SA, Khan H, Baloch MR, Chohan AN. Time of Emergence

of permanent teeth of the children of Larkana, Pakistan. Pak Orthodont J 2022;14(1):21-31

7.

Shahid H, Hassan S, Shaikh AA. Eruption of permanent teeth; assessment

of eruption of permanent teeth according to gender in local population. Professional

Medical J 2018;25(11):1741-6. https://doi.org/10.29309/TPMJ/18.4633

8.

Shourie KL. Eruption age of teeth in India. Ind J Med Res 1946;34(1):105-18.

9.

Reis CL, Barbosa MC, Henklein S, Madalena IR, de Lima DC, Oliveira

MA, et al. Nutritional status is associated with permanent tooth eruption in a

group of Brazilian school children. Global Pediatr Health 2021;8:1-6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X211034088

10. Lailasari D, Zenab Y, Herawati E, Wahyuni IS. Correlation between permanent

teeth eruption and nutrition status of 6-7-years-old children. Padjadjaran J Dent

2018;30(2):116-23. https://doi.org/10.24198/pjd.vol30no2.18327

11. Arid J, Vitiello MC, da Silva RA, da Silva LA, de

Queiroz AM, Küchler EC, et al. Nutritional status is associated with permanent tooth

eruption chronology. Brazilian J Oral Sci 2017;16:1-7. https://doi.org/10.20396/bjos.v16i0.8650503

12. Dimaisip-Nabuab J, Duijster D, Benzian H, Heinrich-Weltzien

R, Homsavath A, Monse B, et al. Nutritional status, dental caries and tooth eruption

in children: A longitudinal study in Cambodia, Indonesia

and Lao PDR. BMC Pediatr 2018;18:300. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1277-6

13. Ethnic groups in Pakistan: Major ethnic

groups in Pakistan. Accessed on: August 13, 2022. Available

from URL: http://ethnicityinpakistan.blogspot.com/2012/10/ethnic-groups-in-pakistan.html

14.

Anonymous.

Balochi culture. Accessed on: August 13, 2022. Available from URL: https://historypak.com/balochi-culture

15. Ali SS, Masood A, Abid S. Women literacy

in Baluchistan: Challenges and way forward. Eur J Sc Res 2018;148(4):460-73.

16. Šindelářová R, Žáková L, Broukal Z. Standards for permanent tooth emergence

in Czech children. BMC Oral Health 2017;1:140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-017-0427-9

17. Chaitanya P, Reddy JS, Suhasini K, Chandrika IH, Praveen D. Time and

eruption sequence of permanent teeth in Hyderabad children: A Descriptive cross-sectional

study. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent 2018;11(4):330. https://doi.org/10.5005%2Fjp-journals-10005-1534

18. Vithanaarachchi N, Nawarathna L, Wijeyeweera L. Standards

for permanent tooth emergence in Sri Lankan children. Ceylon Med J 2021;66(1):44-9. https://doi.org/10.4038/cmj.v66i1.9348

19. Gutiérrez-Marín N, Soto AL, Rivas JC. Age and sequence of

emergence of permanent teeth in a population of Costa Rican Schoolchildren. Odovtos-Int

J Dent Sci 2021:325-32. http://doi.org/10.15517/ijds.2021.43991

20. Elkhatib M, El-Dokky N, Nasr R. The emergence sequence of primary

and permanent teeth in a group of children. Egyptian Dent J 2021;67:41-54, https://doi.org/10.21608/edj.2020.46954.1297

21.

Evangelista S, Vasconcelos

KR, Xavier TA, Oliveira S, Dutra AL, Nelson-Filho P, et al. Timing of permanent

tooth emergence is associated with overweight/obesity in children from the Amazon

Region. Brazilian Dent J 2018;29(5):465-8. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6440201802230

22.

Pahel BT, Vann Jr WF, Divaris K, Rozier RG.

A contemporary examination of first and second permanent molar emergence. J Dent

Res 2017;96(10):1115-21, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022034517716395

23.

Rouhani MH, Salehi‐Abargouei A, Surkan PJ, Azadbakht L. Is there a

relationship between red or processed meat intake and obesity? A systematic review

and meta‐analysis of observational studies. Obes Rev 2014;15(9):740-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12172

|

AUTHORS'

CONTRIBUTIONS

Following authors have made substantial contributions to the manuscript

as under:

NK:

Concept and study design, analysis and interpretation of data,

drafting the manuscript, critical review, approval of the final version to be

published

MuRB,

HK, AC, SAA: Concept and study design, acquisition of data, drafting the

manuscript, approval of the final version to be published

Authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in

ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the

work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

|

|

CONFLICT

OF INTEREST

Author declared no

conflict of interest

GRANT SUPPORT

AND FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE

This study is

funded by the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan

|

|

DATA SHARING

STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available

from the corresponding author upon reasonable request

|

|

This is an Open Access

article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial

2.0 Generic License. This is an Open Access

article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial

2.0 Generic License.

|

![]() https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2023.23075 ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2023.23075 ORIGINAL

ARTICLE![]() , Mujeeb ur Rehman Baloch 2, Hasham Khan 3,

Arham Chohan 4, Sarfraz Ali Abbasi 5

, Mujeeb ur Rehman Baloch 2, Hasham Khan 3,

Arham Chohan 4, Sarfraz Ali Abbasi 5