![]() https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2023.22212 SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2023.22212 SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Potential efficacy of Turmeric as an anti-inflammatory agent and antioxidant in the treatment of Osteoarthritis

Sana Qayyum1 ![]() ,

Asghar Mehdi1

,

Asghar Mehdi1

|

1: Fazaia Ruth Pfau Medical College, Air University, P.A.F Base Faisal, Karachi, Pakistan Email Contact #: +92-321-8941805 Date Submitted: November 15, 2021 Date last revised: August 18, 2023 Date Accepted: August 19, 2023 |

|

THIS ARTICLE MAY BE CITED AS: Qayyum S, Mehdi A. Potential efficacy of Turmeric as an anti-inflammatory agent and antioxidant in the treatment of Osteoarthritis. Khyber Med Univ J 2023;15(3):190-7. https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2023.22212 |

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: To elaborate anti-inflammatory and antioxidant role of turmeric in management of osteoarthritis.

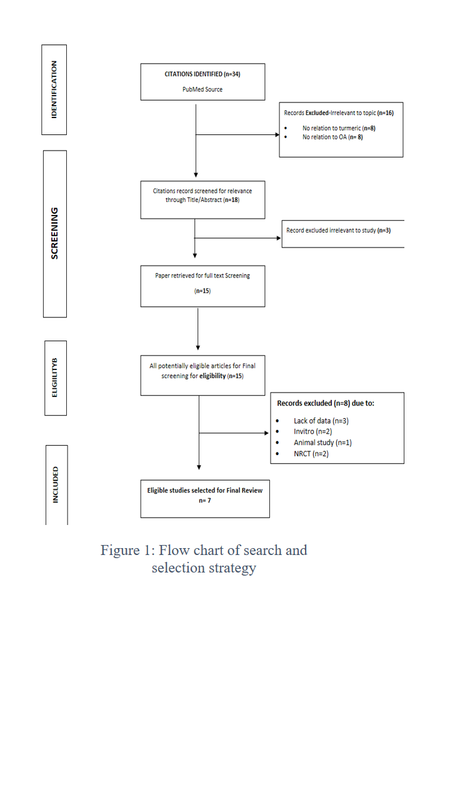

METHODS: In this review article, we focused on the anti-inflammatory properties of turmeric, documented by randomized controlled trials and review articles published from 2011-2020 in PubMed. Out of 34 articles found, 27 were excluded on the basis of animal/in-vitro studies, with insufficient data, not related to turmeric and osteoarthritis, and non-randomized controlled trials. Studies taken into consideration were of shorter durations ranging from 4 weeks to 4 months. Finally, seven studies were shortlisted which highlighted the importance of turmeric as an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agent. Five studies compared turmeric with Non-Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) while two compared its affects with placebo.

RESULTS: The review results exhibit anti-inflammatory & anti-oxidant properties of curcumin to minimize wear & tear of articular cartilage. It limits progression of disease and reduces the requirement of analgesics, thus protects from potential adverse effects. The p-value of <0.05 was considered as significant and confidence interval (CI) 0.58-0.79 in curcumin groups compared to NSAIDs group CI range 0.53-0.82. Two studies with placebo also showed statistically significant with higher and lower formulations of curcumin intake.

CONCLUSION: Prolonged use of NSAIDs in osteoarthritis is associated with serious gastrointestinal and cardiovascular adverse effects. Use of turmeric can play a pivotal role in management keeping patient safety and reducing the requirement of NSAID’s in osteoarthritis. In addition, it can be used as adjuvant or alone in patients and is an economical option with minimal side effects compared to NSAIDs.

KEYWORDS: Curcuma (MeSH); Turmeric (MeSH); Osteoarthritis (MeSH); Randomized controlled trials (Non-MeSH); Antioxidants (MeSH); Anti-Inflammatory Agents (MeSH).

INTRODUCTION

The term Turmeric is derived from Latin terra meritia meaning “meritorious earth”, which refers to the colour of ground.1 Its chemical name is Curcuma longa belonging to the ginger family Zingiberaceae, largely grown in South East Asia & North Australian region. The active ingredient of Curcuma longa is curcuminiods, responsible for its bright yellow color. The color is due to the polyphenolic pigments; along with Demethoxycurcumin, bismethxycurcumin, volatile oils and miscellaneous components like resins, sugars and protein.2,3 Curcuma longa use as a medicinal plant is since Ayurvedic times owing to its potent anti-inflammatory, antioxidant as well as anti-apoptotic traits.4-6 The role of turmeric as antimicrobial, neuroprotective, cardioprotective, anti-tumorigenic and as an immunomodulating agent has evolved with time, however more work in terms of clinical trials is still required.7-9 The anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of turmeric assists in management of chronic inflammatory states such as in arthritis.

Arthritis is derived from the Greek words “artho” and “itis” meaning Joint inflammation. Of the 100 forms, osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common and leads to chronic pain disability.10 It is the leading cause of ailment in developed world, influencing 10% of the population worldwide.11 WHO report on global burden of disease (2013) makes it the fourth principal cause of disability in men and eighth in women.12 In Asian countries, OA prevalence ranges from 38.1% to 46.8% with an increasing trend.13 It involves wear and tear of joint cartilage, meniscus, ligaments resulting in bone outgrowth.14 Knee is the most common joint being affected followed by hip and hand joints, causing impairment with advancing age and obesity.11 The etiology of OA is multifactorial, including local and systemic factors however the previous knee trauma and stress on joint can act as potential risk factor leading to pathological inflammation. Other risk factors include; advancing age, increased body weight, metabolic disease, diet, smoking, increased bone density, and muscle function. The most common clinical manifestation is pain, morning stiffness, joint swelling, and difficulty in walking, limited range of joint movements resulting in poor quality of life, immobility, increased morbidity and mortality hence ultimately increasing the disease burden. The increase in inflammatory cytokines such as Interleukin-1 (IL-1), Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in turn activates metalloproteinase, collagenase, gelatinase and aggrecanase resulting in damage to cartilage and joint tissue.15 The release of free radicals, Nitric Oxide, superoxide anions from macrophages and mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to death of chondrocytes.16

With advancing times, different modes of management are now available in treating OA. The non-pharmacological options comprise of patient education to avoid risk factors, aerobic and strengthening exercises to preserve the joint mobility.17 The Pharmacological options available include; NSAIDS, Acetaminophen, corticosteroids and duloxetine. The Surgical options available include total knee arthroplasty and rehabilitation.15 Recently other options such as stem cell therapy and Platelet rich plasma (PRP) have also been tried to relief pain of OA with varied results.18,19

The objective of this review was to establish the efficacy of turmeric as an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agent and establish its potential role in alleviation of symptoms and treatment of osteoarthritis by reviewing randomized controlled (clinical) trials published during last 10 years (2011-2020).

METHODS

Article Evaluation and Selection

All the articles included in this review are taken from PubMed, published during last 10 years (from 2011-2020), searched by the keywords “curcuma longa” or “curcuma” or “turmeric” or “curcumin’ or “arthritis” or “osteoarthritis” or ‘randomized controlled trials” or “clinical trials”. Animal studies, in vitro studies, studies with no relation to turmeric and osteoarthritis, studies with insufficient data, and non-randomized controlled trial articles were excluded. All prospective randomized controlled (clinical) trials using curcuma lounga and its extract for treatment of OA in English language were included. This review of seven randomized controlled trials shows efficacy and potential of turmeric in treatment of OA. The studies included were of shorter durations ranging from 4 weeks to 4 months’ (Figure I showing the flow chart for selection of studies). Nevertheless, these studies have highlighted the role of curcuma longa in inflammatory and oxidative conditions like OA and have warranted the need for longer duration trials.

Subjects and Interventions

The study subjects were diagnosed cases of OA as per American college of Rheumatology criteria (ACR) for OA and Kellgren-Lawrence criteria, findings on X rays were present. The five out of seven randomized controlled selected studies compared the curcumin and Non- steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) while the two included studies shows the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effect of curcumin against placebo used in management of OA patients. (Table I showing summaries of shortlisted studies)

Table I:Summary of trial findings and interventional strategies

|

First author (year), reference |

Sample Size |

Inclusion criteria |

Study duration |

Preparation of turmeric extract and curcumin (powder) |

Experimental intervention (type, dose and duration) |

Control of intervention (type, dose and duration) |

Primary outcome |

|

Kertia N., (2012), 15

|

73 |

Age range 58 to 64 years, with mild to moderate knee OA, confirmed by ACR criteria. |

4 weeks |

Ethanolic extracts of curcuminiods. |

30mg of curcuminoids extracted three times daily. |

25 mg of diclofenac sodium three times daily. |

COX-2 enzyme secretion |

|

Kuptniratsaikul V., (2014), 13 |

367 |

Age≥ 50years,

Knee OA patients with knee pain score of ≥5 out of 10 and confirmed in accordance with ACR, and on X-rays, according to Kellgren–Lawrence criteria |

4 weeks |

Ethanolic extracts of curcuminiods. |

1,500 mg/day of C. domestica in the form of 2 capsules after meal 3 times a day for 4 weeks. |

1,200 mg/day of ibuprofen after meals 3 times a day for 4 weeks. |

WOMAC total, pain, stiffness and function, 6minute walk distance |

|

Ross MS (2016), 11 |

367 |

Age range (50 years or older),

Confirmed OA by criteria of ACR and on X-rays. |

4 weeks. |

Curcumin extract (consisted of a 75% to 85% curcuminiods ) |

1500 mg daily of curcumin extract

Administered 2 capsules per meal, 3 times a day for 4weeks.

|

Tablet ibuprofen 1200mg 3 times a day for 4 weeks. |

WOMAC index, 6-minute walk distance |

|

Haroyan A (2018), 20 |

201 |

Age range of 40-70years male and females with primary hypertrophic OA of knee joint bone, grade I to III by Kellgren-Lawrence criteria. |

12 weeks |

Each capsule of CuraMed 500mg contains 552–578 mg of BCM-95® as a dry extract, from Curcuma longa rhizome.

1 capsule daily 3 times for 12 weeks |

Each capsule of Curamin 500mg contains 350 mg BCM-95® and 150 mg Boswellia serrata

1 capsule daily 3 times for 12 weeks. |

Placebo capsules contained 500 mg excipients, maltodextrin, calcium phosphate, gelatin, magnesium stearate, silica dioxide, FD&C yellow 5, FD&C yellow 6, and titanium dioxide.

1 capsule daily 3 times for 12 weeks. |

WOMAC for pain, stiffness and function

Physical Assessment |

|

Henrotin.Y (2019), 21

|

150 |

Age range (45years- 80 years)

OA patients of knee joint acc. to ACR criteria

Knee with score of 40mm on 0-100mm visual analog scale (VAS) |

3 months |

Curcuma longa from rhizome extract |

1. Placebo 2 x3 caps

2. bio-optimized curcuma longa extracts (BCL) low dosage 2 x 2 caps/day +placebo 2 x1 cap/day

3. BCL high dose 2 x 3caps/day

Capsules taken twice daily once at breakfast, one at dinner |

Each capsule contained curcuma longa 46.67mg with polysorbate 80 and citric acid.

The Placebo capsule contained sunflower seed oil. |

PGADA

sColl2-1 |

|

Shep D., (2020), 12 |

140 |

Age range (38years-65years) with OA for at least 3months,

Confirmed OA by criteria of ACR and on X-rays. VAS of 4 or more. |

4 weeks |

Curcuminiods complex (curcuminiods and essential oil ) |

Curcuminiods complex 500mg plus diclofenac 50mg (individual capsule and tablet simultaneously administered

Twice daily for 4weeks.

|

Tablet Diclofenac 50mg twice daily for 4 weeks. |

PVAS

KOOS

|

|

Heidari‐Beni M (2020),22

|

60 |

Age range (35-75 years)

Mild to moderate knee OA (grade II-III)

|

4 weeks |

Ethyl acetate used to preserve antioxidant property of formulation |

Herbal formulation (n=30) curcumin (300mg), gingerols (7.5mg), piperine (3.75mg) 2times daily for 4 weeks. |

Naproxen (250mg)

2 times daily for 4 weeks

|

PGE2 |

COX-2, Cyclooxygenase 2 enzyme; PVAS, pain visual analogue score; ACR, American college of rheumatology; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; PGDA, Patient Global Assessment of disease severity; sColl2-1, a biomarker of cartilage degradation; KOOS, Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score.; PGE2, Prostaglandin E2 levels

RESULTS

Pain being the chief compliant in OA is measured by Pain visual Analogue Score (PVAS) and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) scales.23 Few studies includes Knee Injury and OA outcome Score (KOOS), Patient global assessment of disease severity (PGDA) on 100mm visual analogue score (VAS) and a serum collagen 2-1 (sColl2-1) levels; a specific amino acid sequence located on type 2 collagen and considered as a biomarker of cartilage degradation as primary outcomes.12, 21

A Prospective randomized open end blinded evaluation (PROBE) study of 80 OA patients diagnosed according to ACR with average age of 64.05±8.83 years by Kertia N., et al15 compared efficacy of curcuminoids to diclofenac sodium in randomly allocated groups of Curcuminoid (n=39) and diclofenac (n=41). Thirty four patients completed study in curcuminoid group and 39 in diclofenac group, five and two patients drawn out from each group due to various reasons such as exacerbation of co-morbid, adverse effects or either on request of family respectively. Paracetamol was used as a rescue medication when required. After 4 weeks COX-2 enzyme secretion by synovial fluid monocytes was significantly decreased by 0.58 and 0.79 before and after treatment in curcuminoid group with a P value <0.001 & 95%CI. In diclofenac groups 0.53 and 0.82, before and after treatment with a P value of <0.001 & 95%CI. During treatment COX-) enzyme secretion by synovial fluid monocytes decreased by -0.19 and 0.26 in 95%CI and P value of 0.89 in both groups.

In other study conducted by Kuptniratsaikul V, et al a randomized controlled trial, a total of 524 patients were screened for OA. Three hundred sixty-seven patients selected having grade II-IV severity according to Kellgren Lawrence criteria on Xray with pain score of ≥ 5out of 10 according to ACR. These 367 patients were distributed randomly in two parallel groups, curcuminoid group n= 185 took 1500mg/day of curcuma domestica in form of capsules and NSAID group n= 182 took 1200mg/day of ibuprofen after meals for 4 weeks. The study completed by n=171 curcuminoid group and n=160 NSAID group members. 14 and 22 patients from each group withdrew due to adverse effects, inability to contact and inconvenience of individuals discretely. Improvement in all WOMAC scores in C. domestica extract group seemed to be better than those in ibuprofen group. The mean difference (95% CI) of WOMAC total, WOMAC pain, and WOMAC function scores at week 4 compared to values at week 0 of C. domestica extracts except for the WOMAC stiffness subscale, which showed a trend towards significance (P=0.060), were non-inferior to those of the ibuprofen group (P=0.010, P=0.018, and P=0.010, respectively).The 6minute walk distance at week 4 was approximately 348±86.0 m in ibuprofen and 345.43±91.66 m in curcuminoid group separately. Most subjects were contented with treatment by satisfaction index showing 95.6% and 97.1% in Ibuprofen and curcuminoid groups singly. The improvement in Global assessment was observed in 63.8% and 64.3% in Ibuprofen and curcuminoid group respectively. Patients were allowed to take tramadol as rescue medication, though few patients used rescue medication and had minimal effect on results, this approach may not exhibit recent practices.13,15 One of the limitations of study was the average baseline score showing approximately 5 and ranged from 3 to 7 out of 10. This meets the inclusion criteria, adding patients of lower pain scores may have made impact on result making it more favorable.

In another study by Ross MS., a randomized double blind controlled multicentric clinical trial in which 367 patients of OA confirmed by ACR and on Xray’s according to Kellgren Lawrence criteria were enrolled. The mean age of subjects was 60 years, with majority comprised of women (~90%). These 367 patients are randomly allocated, n=185 curcumin extract and n=182 in ibuprofen groups, 171 and 160 patients completed study in curcumin extract and ibuprofen groups discretely. The individuals were administered 1500mg/day of curcumin extract and 1200 mg/day of Ibuprofen for 4 weeks. All WOMAC scores were more than 5 out of 10 at baseline with no difference between respective groups. WOMAC Index and 6-minute walk distance scores were assessed at week 2 and week 4. Improvement in all WOMAC scores in both groups as compared to baselines with P value <0.001. A non-inferiority test (95% CI) in curcumin group revealed the mean difference of WOMAC total (P=0.010), Pain (P=0.018), and function (P=0.010) subscale scores at week 4, indicating similar improvements in both groups. The 6-minute walk distance was observed as 304m in ibuprofen and 310m in the curcumin groups, improvement in both groups observed after 4 weeks. The adverse events like abdominal discomfort and distension were markedly notable in ibuprofen group than the curcumin group, overall lesser side effect profile in curcumin group was observed. Patient satisfaction was 97% in curcumin and 96% in ibuprofen groups separately. Patients were restrained to use further medications, except tramadol for severe pain.11

A randomized double blind three arm placebo-controlled study conducted by Haroyan A., et al in which 210 patients of OA were primarily identified. Two hundred one patients were enrolled out of which 179 completed the study. The random allocation in three groups was done with Curamin® group n=67, CuraMed group n= 66 and Placebo group n= 68. The mean age of individuals was 56.2 years, with female dominance (~93%), average Body mass index (BMI) of 29kg/m2 and disease severity of grade I-III by Kellgren Lawrence criteria. The duration of study was 12 weeks,22 participants dropped out of study; five from Curamin®, eight from CuraMed group and nine from placebo groups due to various reasons such as inability to follow up, adverse effects, lack of interest, mistrust of medicine and lack of improvement from each group respectively. The WOMAC total (pain, stiffness, function) and Physical assessment were the primary outcomes. A Pronounced effect of Curamin® compared to placebo was noted both in physical performance tests and the WOMAC joint pain index, (P<0.005) while higher efficacy of CuraMed vs. placebo was seen only in physical performance tests (P>0.05). The effect size compared to placebo (-0.146) was same in both treatment groups but was higher in the Curamin® group (-0.404) compared to CuraMed group having (-0.515). However, the treatments were well tolerated with minimal side effects 3% in Curamin® group, 10.6%in CuraMed and 5.9% in Placebo groups observed. This study shows efficacy of curcumin superior when used with other anti-inflammatory agents like Boswellia serrata as compared to its use alone vs the placebo control.20,24

A double blind multicenter randomized placebo controlled three arm study conducted by Henrotin Y., et al., in 2019.Total Patients enrolled were 150, randomly allocated into three groups. The Placebo group (n=47) 2 x 2 capsules per day, the bio-optimized curcuma lounga extracts (BCL) low dosage group (n=49) 2x2 capsules per day plus placebo 2 x 1 capsule per day and BCL high dosage group (n=54) taking 2x 3capsules per day separately. Paracetamol or NSAIDs 500mg not to exceed 3 g/day were allowed as rescue medication. The Patient global assessment of disease activity (PGADA) and serum scoll 2-1 levels were used as primary outcome with KOOS and PVAS as secondary outcomes. Low and high dose BCL groups exhibited a significant reduction of Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity than Placebo group. Decrease in serum sColl2-1 secretions in all groups with p value <0.01 with no differences between groups. Higher Pain reduction in low and high dose BCL groups (-29.5mm and -36.5mm) as compared to placebo (-8mm; P= 0.0018) at day 90. The global KOOS score significantly decrease over time but changes were close between treatment groups. High dose BCL group showed adverse effects higher with P value of 0.012, in comparison to Placebo group. The study showed the positive trends in PGADA, serum levels of OA biomarkers and the significant pain reduction in OA patients.21

The prospective randomized open parallel group study by Shep D. et al, compared the efficacy of curcuminoid - diclofenac complex with diclofenac alone. One hundred sixty-one participants were screened, 150 were enrolled, confirmed on Xray’s; out of these totals of 140 participants completed the study. The curcuminoids complex (500mg) + diclofenac (50mg) group n=71 and diclofenac group (50mg) had n= 69. Patients with curcuminoid complex plus diclofenac group exhibit enhancement in KOOS subscales of pain and quality of life, (p<0.001) compared to diclofenac alone. There was no statistically significant difference found between both groups. However, minimal additional rescue analgesic agent uses such as Paracetamol (3% as compared to 17%), lesser side effects (13% as compared to 38%) and use of histamine blockers such as ranitidine (6% compared to 28%) are observed in curcuminoids plus diclofenac groups than Diclofenac group alone.12

In a double blind, two arm parallel group randomized controlled trial conducted by Heidari‐Beni M, et al., in 2020, compared the effect of herbal formulations such as turmeric extract, black pepper, and ginger versus Naproxen in a 4 weeks’ study. OA grade II-III patients were randomly allocated in two groups. Each group having 30 OA patients out of 60 who met the criteria. The Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) levels was used as primary outcome scores. All subjects completed the study. PGE2 decreased notably in both groups with P<0.001, but no statically significant difference in both groups observed. The limitation of study was the lack of other inflammatory markers assessment, especially Tumor necrosis factors α (TNF- α) and Interleukins (ILs).22

DISCUSSION

This review article provides the recent evidence of potential efficacy of turmeric being an anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant agent in treating OA patients. Though the exact biochemical cause of OA remains unclear, the available data shows its association with inflammation, and free radical injury of articular cartilage, resulting in pain and malfunction of the affected joints such as knee, hip and hands. The most common treatment modalities are NSAIDs.15 Prolonged use of NSAIDs are associated with serious adverse effects involving gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and hepatic systems. This makes herbal therapy, which can alleviate pain and inflammation as potential primary or adjunct options for reducing arthritis symptoms.25 The table II provides a brief outline for each study included in review article regarding the severity of OA & usage of Turmeric, NSAIDs along with rescue medication. The potential significant properties of curcumin make its role in immunomodulation, as an anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant agent and can be used as a safe alternative adjuvant to NSAIDs in managing patients with or without co-morbid facing significant adverse effects. 11-13,15,22 The duration of treatment with herbal medicines can be done for longer periods with less chances of significant adverse effects and toxicities as compared to NSAIDs alone.11-13,15,22,26 In one of the studies, the analgesic effect of Curcumin and Boswelic acid (another anti-inflammatory agent) was compared with NSAIDs. This study exhibits improvement in symptoms, mainly pain and safer profile in terms of adverse effects .20,21 In another study the efficacy of low and high dose curcumin was compared to the NSAIDs. This study shows dose related efficacy of curcumin as a better analgesic, with increased chances of side effects seen as compared to low dose curcumin. Also, there was less frequency of rescue medication usage observed with curcumin compared to NSAIDs. The use of Placebo has insignificant effect on improvement of symptoms.12,20,21

The similar review of Perkins K., et al., on efficacy of curcumin for treatment of OA patients was conducted in 2017 showed the similar effective results in managing patients though the review has no specified time trend. The included studies compared curcumin efficacy with NSAIDs, Placebo and glucosamine. The major limitation observed was common comorbidities like hypertension and diabetes patients were excluded in some studies, shorter span studies, with small sample sizes and subjective assessment of PVAS.27 Curcumin causes inhibition of cytochrome isoenzymes and p-glycoprotein resulting in pharmacokinetic variations of cardiovascular medications, antibiotics, antidepressants, chemotherapeutic drugs, anticoagulants, and antihistamines. Therefore, its consequent use with few conventional drugs should be done carefully.28 However, most of these novel products seem to be safe.

Conclusion

This review provides knowledge regarding possible beneficial role of curcumin in daily diet. It can safely be concluded that use of curcumins either as standalone or as adjuvant therapy to osteoarthritis patients is helpful in reducing the NSAID’s dose / frequency with less chances of NSAID related side effects. The use of Curcuma along with other non-pharmacological and pharmacological therapies as economical option may be used in OA patients.

Though the studies used in this review do not have sufficient sample size and were of shorter duration. Further studies on a larger sample size are essential to elaborate efficacy of curcumin’s role in OA patients as it has a well-tolerated adverse event profile and significantly improving symptoms. This review also provides sufficient evidence for larger clinical trials conductance for treating OA.

Table II: Review of clinical studies, efficacy across severity levels, and medication strategies in osteoarthritis treatment

|

Study |

Severity of Disease |

Turmeric |

NSAIDs |

Rescue Medication |

|

Kertia N., 201215 |

Radiological: Mild to moderate knee OA (no grading mentioned) Clinically: PVAS

|

Curcuminoids 30mg 3x a day |

Diclofenac sodium 25mg 3x day |

Paracetamol 500mg |

|

Kuptniratsaikul13 V.,2014 |

Radiological: Grade II-III according to Kellgren Lawrence criteria Clinically: WOMAC total, WOMAC pain, WOMAC stiffness, WOMAC function 6minute walk distance |

Curcuma domestica 1500mg/day |

Ibuprofen 1200mg |

Tramadol in extreme pain only. |

|

Ross SM., 201611 |

Radiological: Confirmed on Xray (no grading mentioned) Clinically: WOMAC total, WOMAC pain, WOMAC stiffness, WOMAC function 6 minute walk distance

|

Curcumin extract 1500mg /day |

Ibuprofen 1200mg |

Tramadol in extreme pain only.

|

|

Haroyan A 201820 |

Radiological: Grade I-III Clinically: WOMAC total, WOMAC pain, WOMAC stiffness, WOMAC function Physical Assessment

|

· Curamin® Capsule 500mg · Cura Med capsule 500mg · Placebo 500mg |

-- |

Paracetamol 500mg (not to exceed 3g/day) or oral NSAIDs when needed. |

|

Henrotin Y., 201921 |

Radiological: No grading mentioned (according to ACR) Clinically: PGADA sColl2-1 levels PVAS and KOOS (Secondary outcomes) |

· Placebo capsule · BCL extracts low dosage · BCL extracts high dosage

|

--- |

Paracetamol 500mg (not to exceed 3g/day) or oral NSAIDs when needed |

|

Shep D., 202012 |

Radiological: No grading mentioned (according to ACR) Clinically: KOOS PVAS |

Curcumin (500mg) + Diclofenac (50mg) |

Diclofenac (50mg) |

Paracetamol (500mg) for Pain. Ranitidine for GI symptoms. |

|

Heidari‐Beni M, 202022 |

Radiological: Grade II-III Clinically: PGE2 levels |

Herbal formulation (Mixodin) Curcumin 300mg Gingerols 7.5mg Piperine 3.75mg |

Naproxen 250mg |

None |

NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; BCL: Bio optimized curcuma lounga; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; PVAS, pain visual analogue score; ACR, American college of rheumatology; PGDA, Patient Global Assessment of disease severity; KOOS, Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score.

REFERENCES

1. Ashraf K, Mujeeb M, Ahmad A, Ahmad N, Amir M. Determination of Curcuminoids in Curcuma longa Linn. by UPLC/Q-TOF–MS: An Application in Turmeric Cultivation. J Chromatographic Sci 2015;53(8):1346-52. https://doi.org/10.1093/chromsci/bmv023

2. Aggarwal BB, Sundaram C, Malani N, Ichikawa H. Curcumin: The Indian Solid Gold. In: Aggarwal BB, Surh Y-J, Shishodia S (eds). The Molecular Targets and Therapeutic Uses of Curcumin in Health and Disease. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2007. p. 1-75. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_1

3. Jurenka JS. Anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin, a major constituent of Curcuma longa: a review of preclinical and clinical research. Alternative Med Rev 2009;14(2):141-53

4. Sharma R, Gescher A, Steward W. Curcumin: the story so far. Eur J Cancer 2005;41(13):1955-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.009

5. Menon VP, Sudheer AR. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin. In: In: Aggarwal BB SY-J, Shishodia S (eds). The molecular targets and therapeutic uses of curcumin in health and disease: Springer, Boston, MA; 2007. pp. 105-25. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_3

6. Bhawana, Basniwal RK, Buttar HS, Jain VK, Jain N. Curcumin Nanoparticles: Preparation, Characterization, and Antimicrobial Study. J Agri Food Chem 2011;59(5):2056-61. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf104402t

7. Ahmad B, J.Lapidus L. Curcumin prevents Aggregation in α-synuclein by increasing Reconfiguration Rate. J Biol Chem 2012;287(12):9193-9. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.325548

8. Kapakos G, Youreva V, Srivastava AK. Cardiovascular protection by curcumin: molecular aspects. Indian J Biochem Biophys 2012;49(5):306-15.

9. Dhama K, Khan S, Tiwari R, Sircar S, Bhat S, Malik YS, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019-COVID-19. Clin Microbiol Rev 2020;33(4). https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00028-20

10. Daily JW, Yang M, Park S. Efficacy of turmeric extracts and curcumin for alleviating the symptoms of joint arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Med Food. 2016;19(8):717-29. https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2016.3705

11. Ross SM. Turmeric (Curcuma longa): Effects of: Curcuma longa: Extracts Compared with Ibuprofen for Reduction of Pain and Functional Improvement in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. Holist Nurs Prac 2016;30(3):183-6.

https://doi.org/10.1097/hnp.0000000000000152

12. Shep D, Khanwelkar C, Gade P, Karad S. Efficacy and safety of combination of curcuminoid complex and diclofenac versus diclofenac in knee osteoarthritis: A randomized trial. Medicine 2020;99(16).

https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000019723

13. Kuptniratsaikul V, Dajpratham P, Taechaarpornkul W, Buntragulpoontawee M, Lukkanapichonchut P, Chootip C, et al. Efficacy and safety of Curcuma domestica extracts compared with ibuprofen in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a multicenter study. Clin Interven Aging 2014;9:451-8. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S58535

14. Park Y-C, Goo B-H, Park K-J, Kim J-Y, Baek Y-H. Traditional Korean Medicine as Collaborating Treatments with Conventional Treatments for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Protocol for a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pain Res 2021; 14:1345-51. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S311557

15. Kertia N, Asdie AH, Rochmah W, Marsetyawan. Ability of curcuminoid compared to diclofenac sodium in reducing the secretion of cycloxygenase-2 enzyme by synovial fluid's monocytes of patients with osteoarthritis. Acta Med Indones 2012;44(2):105-13.

16. Chin K-Y. The spice for joint inflammation: anti-inflammatory role of curcumin in treating osteoarthritis. Drug Design, Dev Ther 2016;10:3029-42. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S117432

17. Page CJ, Hinman RS, Bennell KL. Physiotherapy management of knee osteoarthritis. Int J Rheumatic Dis 2011;14(2):145-51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-185X.2011.01612.x

18. Wang A-T, Feng Y, Jia H-H, Zhao M, Yu H. Application of mesenchymal stem cell therapy for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a concise review. World J Stem Cell 2019;11(4):222-35. https://doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v11.i4.222

19. Chen P, Huang L, Ma Y, Zhang D, Zhang X, Zhou J, et al. Intra-articular platelet-rich plasma injection for knee osteoarthritis: a summary of meta-analyses. J Orthop Surg Res 2019;14(1):385. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-019-1363-y

20. Haroyan A, Mukuchyan V, Mkrtchyan N, Minasyan N, Gasparyan S, Sargsyan A, et al. Efficacy and safety of curcumin and its combination with boswellic acid in osteoarthritis: a comparative, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. BMC Comp Altern Med 2018;18(1):7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-017-2062-z

21. Henrotin Y, Malaise M, Wittoek R, de Vlam K, Brasseur JP, Luyten FP, et al. Bio-optimized Curcuma longa extract is efficient on knee osteoarthritis pain: a double-blind multicenter randomized placebo controlled three-arm study. Arthritis Res Ther 2019;21(1):179. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-019-1960-5

22. Heidari‐Beni M, Moravejolahkami AR, Gorgian P, Askari G, Tarrahi MJ, Bahreini‐Esfahani N. Herbal formulation “turmeric extract, black pepper, and ginger” versus Naproxen for chronic knee osteoarthritis: A randomized, double‐blind, controlled clinical trial. Phytotherapy Res 2020;34(8):2067-73. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6671

23. Bellamy N. WOMAC: a 20-year experiential review of a patient-centered self-reported health status questionnaire. J Rheumatol 2002;29(12):2473-6.

24. Sengupta K, Kolla JN, Krishnaraju AV, Yalamanchili N, Rao CV, Golakoti T, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of anti-inflammatory effect of Aflapin: a novel Boswellia serrata extract. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2011;354(1):189-97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-011-0818-1

25. Eke‐Okoro U, Raffa R, Pergolizzi Jr J, Breve F, Taylor Jr R, Group NR. Curcumin in turmeric: Basic and clinical evidence for a potential role in analgesia. J Clin Pharm Therap 2018;43(4):460-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12703

26. Soleimani V, Sahebkar A, Hosseinzadeh H. Turmeric (Curcuma longa) and its major constituent (curcumin) as nontoxic and safe substances. Phytother Res 2018;32(6):985-95. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6054

27. Perkins K, Sahy W, Beckett RD. Efficacy of curcuma for treatment of osteoarthritis. J Evidence-based Complement Altern Med 2017;22(1):156-65. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587216636747

28. Bahramsoltani R, Rahimi R, Farzaei MH. Pharmacokinetic interactions of curcuminoids with conventional drugs: A review. J Ethnopharmacol 2017;209:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2017.07.022

|

Following authors have made substantial contributions to the manuscript as under:

SQ: Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, approval of the final version to be published AM: Concept and study design, acquisition of data, critical review, approval of the final version to be published Authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. |

|

CONFLICT OF INTEREST Authors declared no conflict of interest

GRANT SUPPORT AND FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE Authors declared no specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors |

|

DATA SHARING STATEMENT The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request |

|

|

|

KMUJ web address: www.kmuj.kmu.edu.pk Email address: kmuj@kmu.edu.pk |